EDITOR'S NOTES

In

this book author Geoffrey Dorman reviews aviation's first half century,

in which he was involved from the earliest years. A nephew of Antarctic

explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, Mr Dorman was personally acquainted

with some of the aviation pioneers, including the Wright brothers. He

saw active service as an RFC pilot during the First World War.

There is a wealth of detail in the book and the text includes items such

as record flights and winners of races and prizes. The author's views

are—not unreasonably—often

subjective rather than objective, being coloured by his obvious

enthusiasm for aviation in general and British aviation in particular.

The author's

optimistic outlook for British aircraft design and manufacture could be

said to have been justified in the case of military equipment but less

so for civil aircraft. In the years after publication of this book only

the Viscount, and to a lesser extent the BAC 1-11, could be truly said

to have been successful commercially. Without doubt interference from

politicians was at least partly responsible for this less than ideal

outcome.

While some of Mr Dorman's predictions for the future

are not unexpectedly wide of the mark others are uncannily close to how

things have actually developed.

We have been unable to trace the

current copyright owner(s) of this

book.

If the owner(s) object to its availability on the Steemrok website,

please write to comms@steemrok.com and the file will be removed without

delay.

Julien Evans

Editor

Steemrok Publishing

2024

steemrok.com

FIFTY YEARS FLY PAST

From Wright brothers to Comet

By

Geoffrey Dorman, A.R.Ae.S.

First Published May, 1951

Copyright, 1951, by

FORBES

ROBERTSON, LTD.

The world's first

practical jet

fighter. The prototype Gloster "Meteor" with those responsible for its

creation. Left to right: John Crosby Warren and Michael Daunt, test

pilots, F. McKenna, Managing Director of Gloster Aircraft Ltd., Air

Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, inventor of the gas turbine, and

George Carter, designer of the

Meteor.

To Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Douglas of Kirtleside, G.C.B.,

K.C.B., M.C., D.F.C., my oldest friend in aviation, 1910 to 1950; whom

I first remember as Sergeant W. S. Douglas of Tonbridge School O.T.C.

Semper eadem!

WHEN I was managing the Information Bureau of the Royal Aero Club in

1946 I looked for a book which would give me the figures and facts of

famous flights, records, and races of the past, so that I could turn up

the answers to questions I was asked. Apart from C. C. Turner's "Old

Flying Days" and Lockwood Marsh's "History of Aeronautics", both

published over twenty years ago, I could find no such book, so I

decided to write one.

To do this has taken four years. I have partly relied on my memory, but

have checked facts and figures from Flight and The Aeroplane, and All the World's Aircraft.

That ever ready help in time of trouble The Aeroplane Directory and

Who's Who in British Aviation has been a constant

source of verification. Facts about the Wrights' first flights are from

Kelly's biography, and the translation of Ader's account of his Avion

"flight" is from Marsh's history. For the past eleven years I have kept

a personal diary which has been of great help.

l have been able to be present at, or take part in, many events and

flights, and to fly about the world on the airlines, mainly because I

have always aimed at establishing a high nuisance value for myself, and

then giving value. If I were left out of anything either by design or

mistake, I made a perfect pest of myself to the people or firms

who ignored or had forgotten me, but when I have been on a

flight or at some function, then I have always tried to give value by

subsequent publicity sooner or later.

Those who feel they have been left out of this book, or treated

inadequately, can console themselves that they have been spared being

plagued by me! Later I shall write further chapters, so the choice is

open either to put up with me, or be left out.

Griffith Brewer [Note 1]

kindly

checked the facts about the Wright brothers and

the founding of the Aero Club. The facts I give about the latter are

not always in accordance with what I am told are in the minutes of the

Club. But minutes are only infallible to bureaucratic minds and I

prefer to rely on accounts told to me by participants soon after. My

thanks are due to Air Commodore J. W. F. Merer for reading the Berlin

Air Lift, Lord Ventry for reading the Airship chapter, John Grierson

the Jet chapter, Alan Marsh the Rotary Wing chapter, and F. A. Dismore

for reading the chapter on records. My thanks also go to Alex Duncan of

R. K. Dundas Ltd. for reading the first typescript. He made valuable

constructive suggestions, which I incorporated.

This is mainly a history of British aviation with facts from other

lands when they impinge on the story.

Omissions have, of necessity, been many; for the canvas is too small on

which to paint the whole vast picture. Selection has not been easy.

I have hardly touched on the wars of 1914 and 1939. Many volumes have

been written on the former and many are being written on the latter.

Parts of some chapters have appeared in Flight, The Aeroplane, Aeronautics,

the Royal Aero Club

Gazette, Canadian

Aviation, Tangmere

Times and Air

Reserve Gazette, to the editors of which I gratefully

acknowledge courtesy for reproduction.

The year 1951 will see the Golden Jubilee of the Royal Aero Club, and

1953 will be the fiftieth Anniversary of the world's first

power-driven, controlled aeroplane flight. So, now that aviation is

reaching its first half century, the new generation may find interest

in looking back to see how it all began. The past seems so refreshingly

real to me.

I would also like to thank R. E. Hardingham, Secretary of the Air

Registration Board, for an almost unlimited supply of A.R.B. obsolete

registration cards with the aid of which I have made my index; this

will, I hope, make the book more airworthy. Thanks are due

also to Captain H. S. (Jerry) Shaw, head of the aviation

department of Shell Petroleum Ltd., for his account of the first civil

flight between London and Paris, in Chapter 8 (Those Were the Days),

which he wrote specially for this book.

GEOFFREY DORMAN.

30

Redburn Street, Chelsea, London, S.W.3.

1st

January, 1951.

Click on the blue dots  to access the various items

directly

to access the various items

directly

Preface

Preface

Contents

Contents

List of illustrations

List of illustrations

Foreword by the Right Hon. Lord

Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.

Foreword by the Right Hon. Lord

Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.

Introduction to the Author, by

Tommy Rose, D.F.C.. A,R.Ae.S.

Introduction to the Author, by

Tommy Rose, D.F.C.. A,R.Ae.S.

1 The

Birth of the Aeroplane

1 The

Birth of the Aeroplane

2 Early

Flying in Europe

2 Early

Flying in Europe

3

The Balloon Goes Up

3

The Balloon Goes Up

4 Royal

Aeronautical Society

4 Royal

Aeronautical Society

5

Flying the Channel

5

Flying the Channel

6 Flying

Grows Up

6 Flying

Grows Up

7 London

to Paris

7 London

to Paris

8 Those

Were the Days

8 Those

Were the Days

9 — And

These are the Days Now

9 — And

These are the Days Now

10 Aviation Becomes

More Commercial

10 Aviation Becomes

More Commercial

11 The London Air

Ports

11 The London Air

Ports

12 First Aerobatics

and Parachutes

12 First Aerobatics

and Parachutes

13 Service Aeronautics

13 Service Aeronautics

14 Military and

Commercial Trials

14 Military and

Commercial Trials

15 First at Tangmere

15 First at Tangmere

16 Flying the Atlantic

16 Flying the Atlantic

17 England to

Australia

17 England to

Australia

18 England to South

Africa

18 England to South

Africa

19 Flying Round the

World

19 Flying Round the

World

20 Kingsford Smith's

Flights

20 Kingsford Smith's

Flights

21 The Schneider

Trophy

21 The Schneider

Trophy

22 The Gordon Bennett

Aviation Cup

22 The Gordon Bennett

Aviation Cup

23 The Aerial Derby

23 The Aerial Derby

24 The Britannia and

Segrave Trophies

24 The Britannia and

Segrave Trophies

25 The King's Cup

Races

25 The King's Cup

Races

26 Flying Challenge

Trophy Races

26 Flying Challenge

Trophy Races

27 Fédération Aéronautique

Internationale

27 Fédération Aéronautique

Internationale

28 World Records

28 World Records

29 F.A.I. and Royal

Aero Club Medals

29 F.A.I. and Royal

Aero Club Medals

30 Gliding

30 Gliding

31 The Light

Aeroplane Movement

31 The Light

Aeroplane Movement

32 Per Ardua to the

Comet

32 Per Ardua to the

Comet

33 The Rise of the

British Aircraft Industry

33 The Rise of the

British Aircraft Industry

34 The Air Shows

34 The Air Shows

35 Jet Propulsion

35 Jet Propulsion

36 The Berlin Air Lift

36 The Berlin Air Lift

37 Into the Second

Fifty Years

37 Into the Second

Fifty Years

38 Rotary Wing Flight

38 Rotary Wing Flight

39 Airships

39 Airships

40 Women in

Aeronautics

40 Women in

Aeronautics

41 Aviators' and

Other Certificates

41 Aviators' and

Other Certificates

42 Fulfilment —

30,000 Miles in 26 Days

42 Fulfilment —

30,000 Miles in 26 Days

43 The Close of the

First Half-Century of Flying

43 The Close of the

First Half-Century of Flying

Postscript

Postscript

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations

Notes

Notes

00 The prototype

Gloster "Meteor",

with those responsible for its creation

00 The prototype

Gloster "Meteor",

with those responsible for its creation

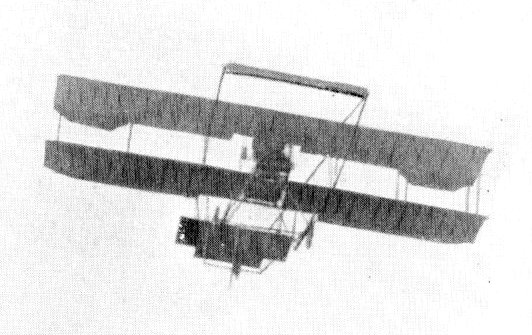

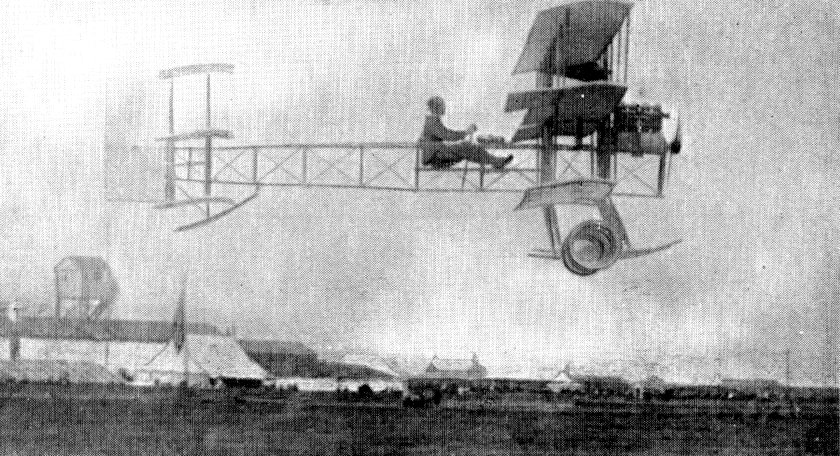

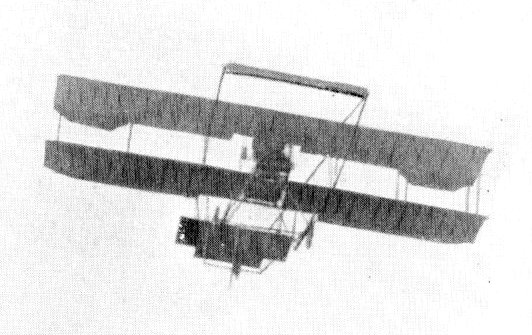

01. Orville Wright

making the first

flight

01. Orville Wright

making the first

flight

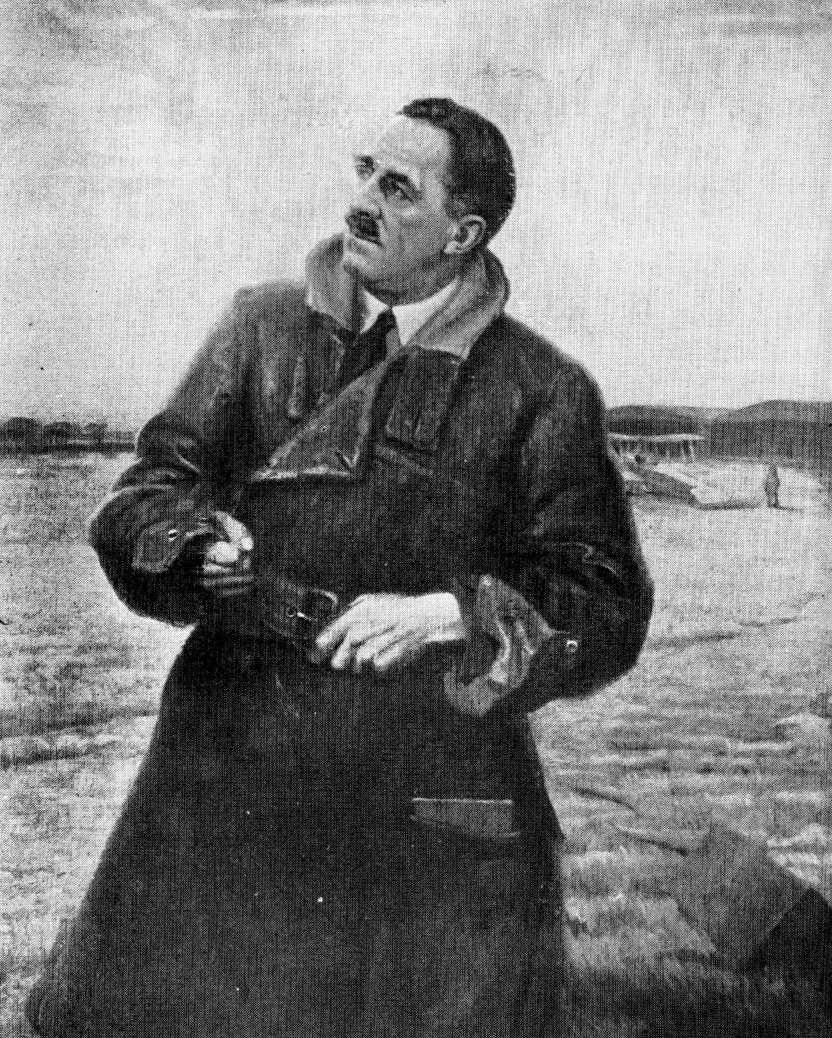

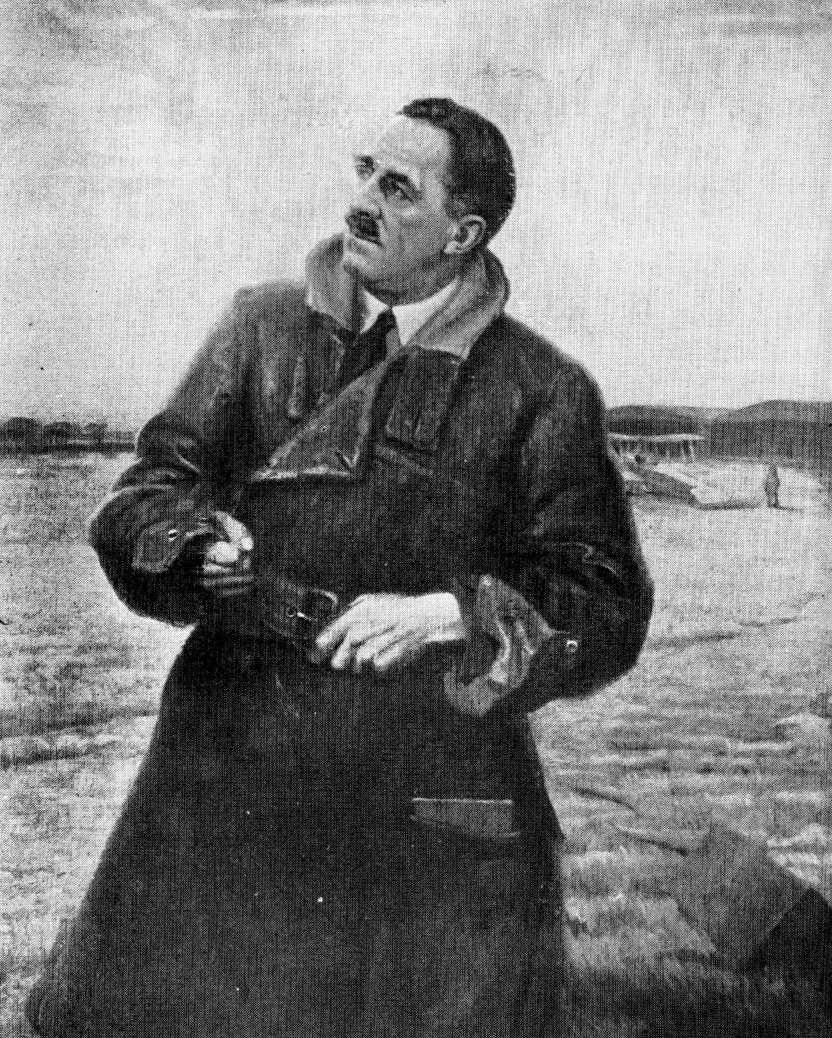

02. Louis Blériot,

having flown the

Strait of Dover

02. Louis Blériot,

having flown the

Strait of Dover

03. The Hon. C. S.

Rolls, a founder

of the Royal Aero Club

03. The Hon. C. S.

Rolls, a founder

of the Royal Aero Club

04. Harold Perrin,

Secretary of the

R.Ae.C., 1905-1945

04. Harold Perrin,

Secretary of the

R.Ae.C., 1905-1945

05. A. V. Roe,

second

Secretary of

the Aero Club

05. A. V. Roe,

second

Secretary of

the Aero Club

06. Air Vice-Marshal

Sir Sefton

Brancker, K.C.B., Director of Civil Aviation, 1922-1930

06. Air Vice-Marshal

Sir Sefton

Brancker, K.C.B., Director of Civil Aviation, 1922-1930

07. Cadet camp at

Farnborough, in

1909

07. Cadet camp at

Farnborough, in

1909

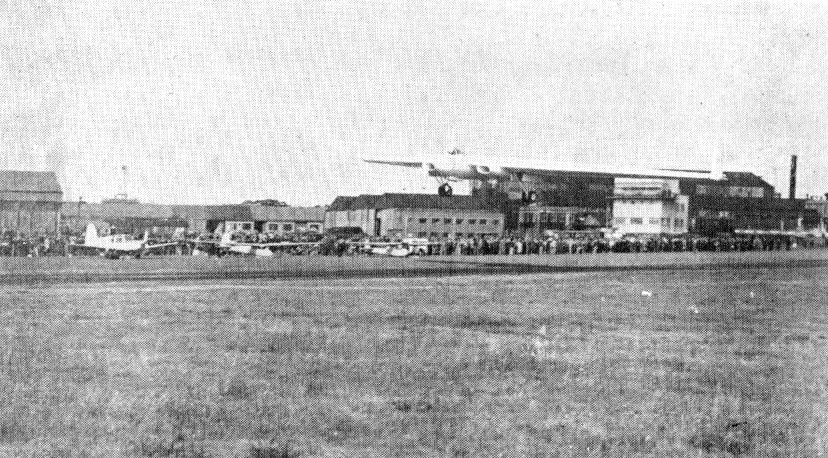

08. Farnborough, in

1949, with a

flying-wing landing

08. Farnborough, in

1949, with a

flying-wing landing

09. Captain Sir John

Alcock and

Lieutenant Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown, the first to fly the Atlantic

direct

09. Captain Sir John

Alcock and

Lieutenant Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown, the first to fly the Atlantic

direct

10. — their Vickers

"Vimy"

(Rolls-Royce "Eagles"), 1919

10. — their Vickers

"Vimy"

(Rolls-Royce "Eagles"), 1919

11. The DH18, in 1920

11. The DH18, in 1920

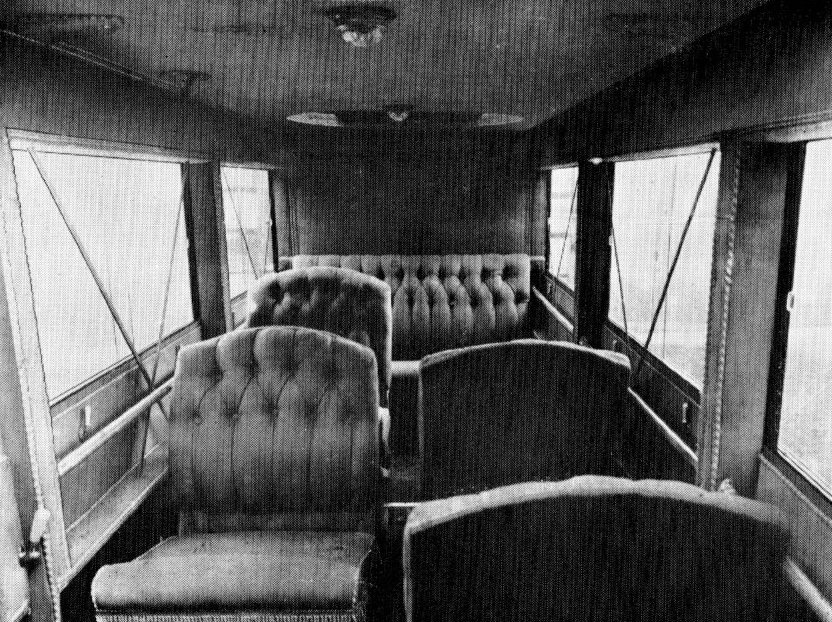

12. Interior of the

DH18

12. Interior of the

DH18

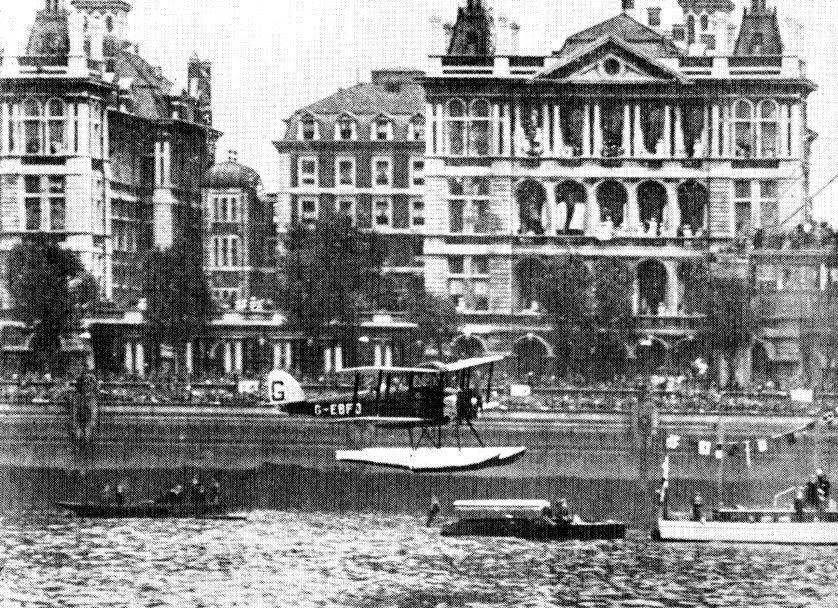

13. Vickers "Viking"

amphibian (450

h.p. Napier "Lion"), 1921

13. Vickers "Viking"

amphibian (450

h.p. Napier "Lion"), 1921

14. Sir Alan Cobham,

alighting on

the Thames, 1926

14. Sir Alan Cobham,

alighting on

the Thames, 1926

15. The first real

airliner: Handley

Page "Hannibal"

15. The first real

airliner: Handley

Page "Hannibal"

16. The racing de

Havilland Comet,

1934

16. The racing de

Havilland Comet,

1934

17. The first fully

successful de

Havilland biplane, 1911

17. The first fully

successful de

Havilland biplane, 1911

18. The first jet

airliner:

prototype de Havilland Comet, 1949

18. The first jet

airliner:

prototype de Havilland Comet, 1949

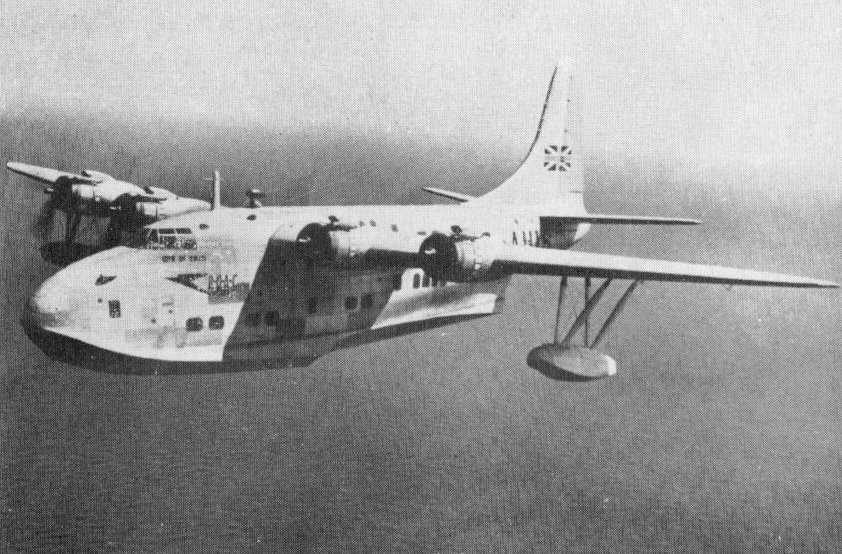

19. Short "C" class

"Empire"

flying-boat, 1937

19. Short "C" class

"Empire"

flying-boat, 1937

20. The B.O.A.C.

marine air port at

Southampton with "Solents" on the water and R.M.S. Queen Elizabeth at

her berth

20. The B.O.A.C.

marine air port at

Southampton with "Solents" on the water and R.M.S. Queen Elizabeth at

her berth

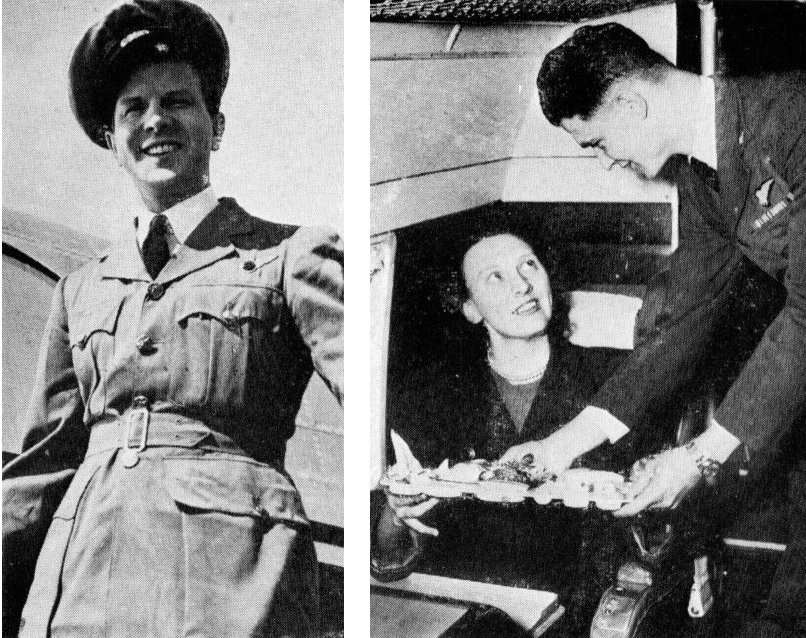

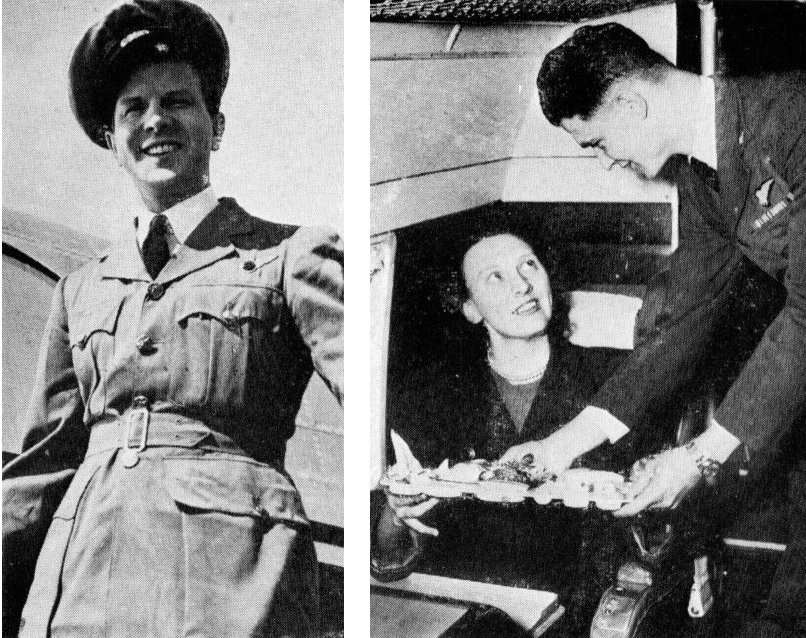

21. & 22.

Stewards Frank Emery (B.O.A.C.)

and Harry McLean (B.E.A.)

21. & 22.

Stewards Frank Emery (B.O.A.C.)

and Harry McLean (B.E.A.)

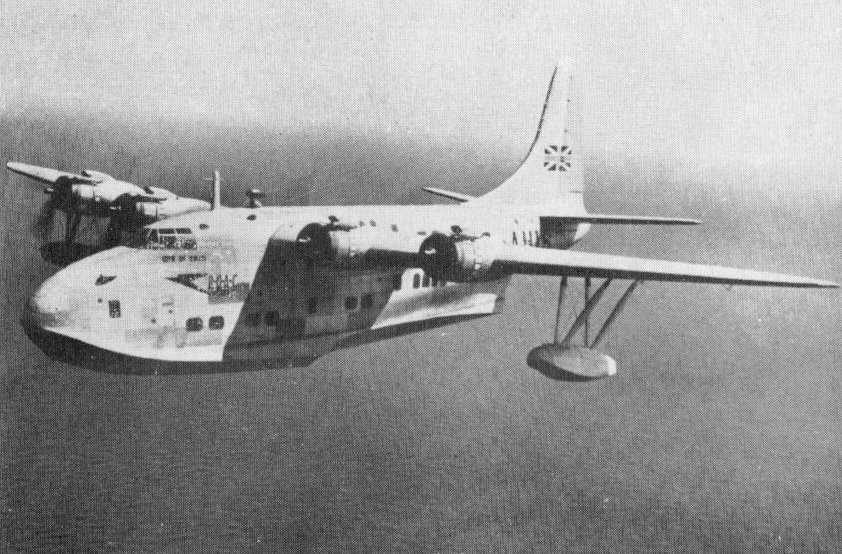

23. B.O.A.C. Short

"Solent"

flying-boat, 1950

23. B.O.A.C. Short

"Solent"

flying-boat, 1950

24. Air Commodore J.

W. F. Merer,

Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Berlin Air Lift, 1948-1949

24. Air Commodore J.

W. F. Merer,

Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Berlin Air Lift, 1948-1949

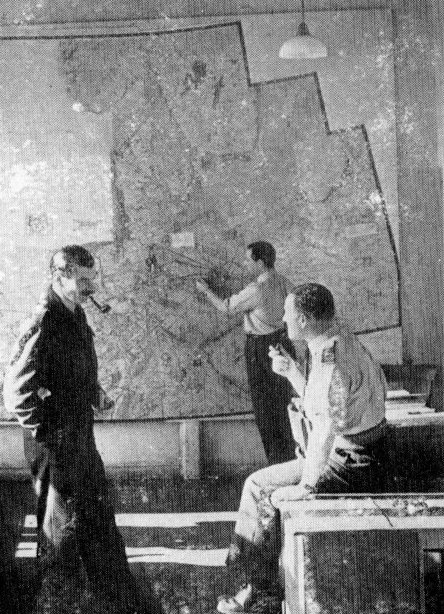

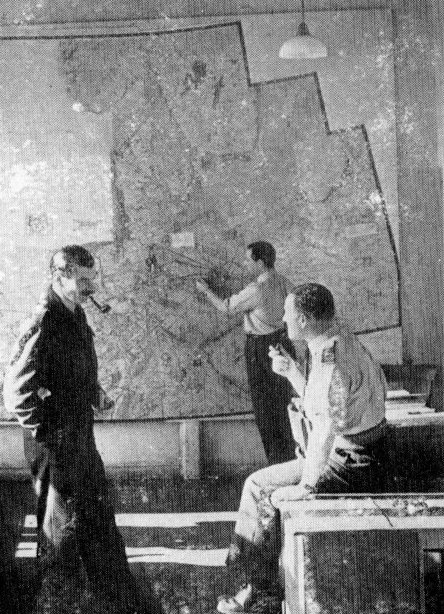

25. Wing Commander

Tim Piper and

Group Captain Brian Yarde, in the control room at Gatow Air Port, Berlin

25. Wing Commander

Tim Piper and

Group Captain Brian Yarde, in the control room at Gatow Air Port, Berlin

26. The single

concrete runway at

Gatow which carried most of the Berlin Air Lift traffic into Gatow for

nearly a year

26. The single

concrete runway at

Gatow which carried most of the Berlin Air Lift traffic into Gatow for

nearly a year

27. F.J. ("Jeep")

Cable, A.F.C.

27. F.J. ("Jeep")

Cable, A.F.C.

28. Alan Marsh, with

the Author, in

the Cierva Air Horse, 1950

28. Alan Marsh, with

the Author, in

the Cierva Air Horse, 1950

29. Bristol

"Brabazon" airliner

alighting after its first flight

29. Bristol

"Brabazon" airliner

alighting after its first flight

30. Canadair 4

("Argonaut"), the

first airliner built in the Commonwealth to go into service

30. Canadair 4

("Argonaut"), the

first airliner built in the Commonwealth to go into service

31. de Havilland

"Albatross" of

1938, from which the Ambassador was developed

31. de Havilland

"Albatross" of

1938, from which the Ambassador was developed

32. Lockheed

"Constellation", the

American intercontinental airliner

32. Lockheed

"Constellation", the

American intercontinental airliner

33. The first

turboprop airliner,

the Vickers "Viscount"

33. The first

turboprop airliner,

the Vickers "Viscount"

34. Airspeed

"Ambassador" airliner,

for B.E.A. in 1951

34. Airspeed

"Ambassador" airliner,

for B.E.A. in 1951

INTRODUCTION

BY

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD

BRABAZON OF TARA.

P.C., M.C., F.R.AE.S.

THE BOY AT school to-day must find it hard to realise that one has not

got to be a very old man to remember a time when the possibility of

flight was looked upon as impossible. In fact the whole

development has occupied under fifty years, and the time at

present is rather critical, for this reason, that soon there will not

be any people who had first-hand experience of the early events and who

can speak of them and about them with full knowledge with the

recollection that they were present.

It is for this reason that the book by Geoffrey Dorman is particularly

welcome at the present time, for he has been known intimately by all

the flying world for many many years, and there is very little that

could be told that he cannot tell us.

I am, indeed, full of admiration for Mr. Dorman for the reason that you

may think that this subject of flight which has been going on now, as I

say, for nearly fifty years, is a narrow one, but that is not at all

the situation; it is a very broad one when you think of its many

separate channels of civil aviation and military aviation to-day. Each

one of them could have a book devoted, very easily, to itself.

Geoffrey Dorman starts right at the very beginning. He puts many of the

very early exploits down in his pages and gives a most interesting

account of the early efforts of organisations like the Royal Aero Club

and the Royal Aeronautical Society. Very right that that sort of thing

should be put down on paper, wrapped up with the names of men who tried

to direct policy in those early days and in fact did it very well.

The canvas that he covers is a very big one and he paints with the

detail of a Canalleto. The result is that this is almost a history of

aviation in all its branches and for that reason, to any student of

these last fifty years who wishes to be reminded of what occurred at

any time, this book will be of great interest; to anyone else who is

unfamiliar with the history of flight this book will be a Bible and a

reference work that should be read by every man and also be in his

library.

BRABAZON OF

TARA.

INTRODUCTION

TO THE AUTHOR BY

TOMMY ROSE,

D.F.C., A.R.Ae.S.

GEOFFREY DORMAN has been in aviation two years longer than I have, and

I have known him most of that time. If any man ever deserved the title

"Enthusiast" he is the one.

Having obtained his Ticket early in 1915 and survived, he underwent a

course of Free Ballooning and his Aeronauts' Certificate No. 44

entitled him to be blown about the world in a balloon. This fact should

also have automatically entailed membership of Colney Hatch!

[Note 2].

For ten years after the First War, Geoffrey served on the staff of the

Aeroplane

under the greatest aeronautical journalist of all time, C. G.

Grey. This association may have permanently furrowed his brow and

greyed his hair, but the end of the period found him one of the most

accomplished air correspondents in the country.

In 1939, despite his prolonged fight and the fact that he had been

medically assessed as "fit for pilot duties," the Royal Air Force

decided he was too old for flying, a fate that befell many of us.

Geoffrey Dorman's great enthusiasm for any job of work connected with

flying at last found something to absorb it when he joined the A.T.C.

and subsequently spent practically every evening of the war instructing

its members.

As soon as A.T.C. gliding started he became a gliding instructor and

his Saturdays and Sundays during this period must have been the longest

ever—anyway they made the rest of the week's work seem child's play.

This joyful period of his life came to an abrupt end in August 1944,

when something blew him out of the sky—he "went in" from 400 feet and

broke a thigh. Well, when one is over fifty this sort of thing cannot

be done with impunity and he is now almost a landlubber.

This book is absorbing because it is written by a man who has lived not

only through this period, but actually in each event, and has known

every personality in its pages. My only regret is that samples of the

Author's own inimitable dry humour do not appear on every page. Perhaps

it is as well, for, being kind-hearted, he would not wish to put Punch

out of business.

TOM ROSE

CHAPTER

1

THE BIRTH OF THE AEROPLANE

The Wright brothers—the

news breaks—Ader's Avion—Langley's "Aerodrome"—Wilbur's

death 1912—Orville's death 1948—Griffith Brewer.

IN

THE last years of the nineteenth century and in the first years of the

twentieth, several inventors were working along independent lines to

achieve controlled flight with machines which were heavier than air and

which depended for their support on either flat or slightly curved

surfaces.

Although there have been various claims for the honour

of having flown first, it is universally now conceded that the first

heavier-than-air controlled power-driven flight was made at Kittyhawk,

North Carolina in the United States of America by Orville Wright in a

biplane designed and built by himself and his elder brother Wilbur.

This machine was powered by an internal combustion motor which

developed about 12 h.p. which was also designed and built by the

brothers.

The brothers had taken their "Flyer", as they called

it, from their home at Dayton to Kittyhawk in North Carolina on the

Eastern seaboard of the United States where they had been making

gliding experiments. They never called the Flyer the "Kitty Hawk",

which name was a much later invention.

By December 1903

they had erected the biplane and all was ready. As there was not much

wind blowing, the Wrights decided to take the machine to Kill Devil

Hill nearby, so as to get extra speed for launching, by running down

the hill. 14th December 1903 was a bright, cold clear day. They tossed

as to who should make the first attempt, and Wilbur won. He started

down the hill, climbed a few feet, stalled, and settled down on the

ground after only three seconds. There was slight damage, enough to

prevent more attempts that day. Repairs were not complete till the

evening of the 16th.

On the morning of 17th December 1903, that

historic day, there was ice on the puddles and a wind was measured as

blowing from 22 to 28 m.p.h. But the Wrights were anxious to continue

experiments so that they could be home for Christmas. Orville said that

with his later experience, he would hardly have risked a flight on a

tried aeroplane in such a wind.

It was Orville's turn first that

day. Because of the wind they decided to start from level ground. The

flight lasted 12 seconds, but

it was the first sustained flight in history under its own power in

which an aeroplane had flown and landed at the same level again. Wilbur

made the second flight—13 seconds—then Orville flew for 15 seconds.

Wilbur made the last flight of the day which lasted 59

seconds—a real flight covering 852 feet against that stiff

wind.

When they were standing discussing the flight, a gust blew the

aeroplane over and damaged it so severely that the possibility of

further flights that year was at an end.

The Press of the world were incredulous. A few papers published

inaccurate accounts. Some inferred the Wrights used an airship with a

gasbag. The Daily Mail

printed a 12-line paragraph near the bottom of a column. This read:

BALLOONLESS AIRSHIP

From Our Own Correspondent

New York, Friday, Dec. 18.

Messrs. Wilbur and Orville Wright, of Ohio, yesterday

successfully experimented with a flying machine at Kittyhawk, North

Carolina. The machine has no balloon attachment, and derives its force

from propellers worked by a small engine.

In

the face of a wind blowing twenty-one miles an hour, the machine flew

three miles at a rate of eight miles an hour, and descended at a point

selected in advance. The idea of a box-kite was used in the

construction of the airship.

Thus was perhaps the most epoch-marking news story in history

reproduced by the most up-to-date newspaper of those times. It was most

inaccurate; for the longest flight of the day—and for many months

after—was 852 feet. The speed over the ground, against that wind, which

was really blowing at a speed from 22-28 m.p.h., may not have

been more than the 8 m.p.h. reported, but the airspeed was about 30

m.p.h.

Practically no other papers in England or anywhere else reported the

flight. There had been many claims of flight by others, which were not

well founded, so the Wrights were not believed.

Wilbur Wright, commenting on the feat, said that it was "the first in

the history of the world in which a machine carrying a man had raised

itself into the air by its own power in free flight, had sailed forward

on a level course without reduction of speed, and had finally

landed without being wrecked."

This flight was the result of much scientific research and experiment.

Wing shapes had been tested in a wind tunnel of a primitive kind, as

also had propellers.

Though the work of the Wright Brothers still has its detractors, the

Wright biplane in almost its original form was a real flying machine,

for in a few years flights of over an hour were made on it with only

minor modifications. The world's first flight of more than one

hour was made on 9th September 1908, when Orville flew for 1 hour 2¼

minutes at Fort Meyer.

Two other inventors claimed to have made flights which pre-dated those

of the Wrights, but their claims could never be established. And in any

case their "flights", unlike those of the Wrights, ended in disaster.

The earliest claim was made by the Frenchman, Clement Ader, who first

studied the problem of powered flight in 1872. Ader claimed to have

"flown" for a distance of 164 feet on 9th October 1890. The machine was

wrecked at the end of the short hop because of lack

of control. That the craft was barely airborne seems to be

confirmed by the fact that while some, including Ader, say the hop

measured 164 feet, others claim that he "flew" 109 yards, which was

presumably the nice round figure of 100 metres! His motive power was a

steam engine said to develop 20 h.p. which drove a 4-blade tractor

screw.

On 14th October 1897 trials of a new machine named the "Avion" were

made at the French military establishment at Satory in the presence of

General Mensier, General Grillon and Lieut. Binet. In an account

published in Paris, Ader described what happened. He wrote: "After a

few metres we started off at a lively pace; the pressure gauge

registered about seven atmospheres; almost immediately the vibrations

of the rear wheel ceased; a little later we only felt those of the

front ones at intervals. Unhappily the wind became stronger suddenly

and we had some difficulty in keeping the Avion on the white line of

the track. We increased the pressure to between eight and nine

atmospheres, and immediately the speed greatly increased, and the

vibrations of the wheels were no longer noticeable . . . The Avion was

then found to be freely supported by its wings. Blown by the

wind it tended continuously to go outside the intended area when it

found itself in a very critical position. The wind blew strongly across

the direction of flight, and the machine though going forward drifted

quickly sideways. We at once put over the rudder to the left as far as

it would go, at the same time increasing the pressure still more,

to try and regain the course. The Avion obeyed, recovered

slightly, and remained for some seconds headed on its intended course,

but it could not struggle against the wind; instead of going back, it

drifted further and further off course, towards the School of Musketry

which was guarded by posts and barriers . . . Surprised at seeing the

earth getting further and further away and rushing sideways at a

sickening speed, we stopped everything. All at once came a great shock,

splintering, and a heavy concussion. We had landed!"

The official description by onlookers credited the Avion with just a

few hops, while others said that it never really left the ground

properly. The real truth may lie in the fact that the French War

Ministry refused further aid. Though, in view of equally discouraging

actions (and other things) by other governments to some of the real

pioneers of flight at later dates, that really does not prove very much.

The consensus of opinion is against the claim of Ader to have achieved

free controlled flight. Many of those who have taken the air after

Ader, and especially those who, taking up gliding, have done their

first "low hops" and have thought they had reached a height of 20 or 30

feet when in fact they were not very much more than two or three feet

up, will appreciate how easily Ader, a complete novice at flying, might

have thought he was really flying when he was only making quite short

hops.

No doubt his pioneer work deserved the niche he made for himself, not

only in French aviation, but in world flying history. As a tribute the

French War Ministry, some years later, decided that all French military

aeroplanes would be called "Avion" in his honour. The term is now used

for almost all French aeroplanes. But it must be remembered that it was

a French general who, after witnessing the episode, testified that the

Avion did not really fly.

It seems exceedingly likely that, if Ader had more skill and

experience, the "Avion" would have flown. But he made the error of

trying to take off down wind. Then he was blown right out of his

prepared area by turning across wind, and the subsequent side drift

would have caused the crash whether he hit the posts or not, for he had

little control.

Another claimant for the honour of having made the first flight was

Samuel Pierpoint Langley, who, when secretary of the Smithsonian

Institute of America, built a monoplane which, he claimed, would have

flown in October 1903—two months before the Wrights' first flight—had not launching accidents

prevented it.

Subsequently, in 1914, parties who were interested in proving that

Langley really would have pre-dated the Wrights if it had not been for

the launching accidents, rebuilt Langley's "Aerodrome" as he named it;

flights were made at Hammondsport, in America. Griffith Brewer

of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom, who was an old friend of

the Wrights, went to America to investigate the Langley claims. He

found beyond dispute that a number of important alterations had been

made to the "Aerodrome" in order to make it rise from the water.

The Smithsonian Institute (which might be compared with the Science

Museum in South Kensington, London) insisted on exhibiting the

"Aerodrome" with an inscription inferring that it was the first

heavier-than-air machine to fly. So in 1928 Orville Wright accepted a

proposal made by the South Kensington Science Museum to loan his

machine for five years, or until it was withdrawn by

him personally. That is why so many people were surprised to

see the original historic Wright flyer in London until 1949. As the

Smithsonian admitted in 1940 that the Wrights were the first to fly,

Orville asked the Science Museum to return the flyer to the Smithsonian

when the war was over. It has been replaced in the Science Museum by an

exact replica made by the students of the de Havilland Technical School.

Discussing Langley's efforts with Griffith Brewer, I said that

Langley's case that he made the world’s first flight seemed a very weak

one. Brewer replied that his case was as weak as his "Aerodrome", the

wings of which broke under the load each time it was launched. Langley

worked on the mistaken assumption that an aeroplane could not fly if

loaded to more than 1 lb. per square foot of wing. I said to Brewer how

fortunate I had been to have come into contact with the Wrights in the

flesh. He paid me the fine compliment that it was fortunate also for

the Wrights, as I was such a fair and sympathetic historian.

Besides being the first to use wind tunnels and to experiment

scientificially, the Wrights were very advanced thinkers. Now, fifty

years after, we are beginning to adopt some of their first ideas as

things new. They realised that it was easier to keep airborne on

limited power than to get off the ground with low power. Their early

aeroplanes were assisted in take-off by means of a weight which was

allowed to fall from a portable derrick about 20 feet high. A rope from

the weight passed over snatch-blocks to the front of a rail and along

the rail to the front of the aeroplane. When the pilot gave the "ready"

signal the motor was opened up fully and the weight was released. This

pull of the falling weight, exerted on the aeroplane, helped the meagre

horse power of the motor to give the aeroplane greater acceleration.

The rope was in fact not attached to the aeroplane itself, but to a

trolley, on which the aeroplane rested, and which ran along the rail.

When the aeroplane reached the end of the rail and was airborne, it

left the trolley behind. When it landed, it came to rest on skids which

formed the undercarriage. The disadvantage was that the aeroplane had

to be brought back to its rail before another flight could be made.

Inventors of aeroplanes later fitted their machines with wheels so that

they could take off again from where they landed. The advantages of the

Wrights' methods were that a greater weight could be kept airborne for

less power, for the weight and extra drag of wheels were eliminated.

Now, although retractable undercarriages have eliminated the

disadvantage of extra drag, commercial airline operators are

investigating the advantages of having some sort of launching trolley

as an undercarriage; the complication and weight of retraction detracts

from the payload. And modern airliners, with a multiplicity of more

reliable powerplants, should not be forced down away from their

destinations, or from some alternative prepared landing ground.

As to assisted take-off, in the 1914-18 war this method was tried for

getting aircraft from the decks of ships. Catapults were tried and have

since been used on service. Rockets were used during the

1939-45 war for getting heavily-laden bombers off the ground. The Mayo

"Composite" was another successful method of assisted take-off,

and other methods are being tried for commercial purposes.

As an example of how, many years later, men were thinking

once again on the same lines as the Wrights in 1903, this item

appeared in the Evening

News in February 1929, more than 25 years after the

Wrights had adopted assisted take-off.

CATAPULTING AN AIR LINER

EXPERIMENTS IN AMERICA AND GERMANY

By Our Air Correspondent

Experiments are being conducted in Germany and America to

decide whether it is practicable to launch a commercial air liner into

the air by some power other than the engine-power of the machine itself.

For

many years certain small ship-fighters have been launched by a form of

mechanical catapult.

Ordinary

air liners, such as the Armstrong Argosies and the Handley Page

16-seaters, can fly on half their available power. Much power is

therefore wasted in getting the craft into the air.

A

heavily laden aircraft, when the ground is very wet and heavy and there

is little or no wind, may require a run of a mile or more to get off

the ground.

The

difficulty here is to give the machine its initial speed to overcome

the resistance of heavy ground.

Various

types of catapult which will impart to an air liner its initial

velocity, and so assist the take-off, are therefore being tested.

Herr

von Opel's famous rocket device is also to be tried.

In 1912 Wilbur Wright contracted typhoid fever of which he died on 30th

May 1912 at the age of 45. He did not live to see his invention reach a

stage at which it has revolutionised the world, nor did he live to

enjoy its financial benefits.

Orville Wright, who died on 30th January 1948, had a narrow escape from

death once. On 17th September 1908 he was flying at Fort Meyer, U.S.A.,

carrying as passenger Lieut. Selfridge of the U.S. Army, who had been

seconded for duty to learn something about flying. One of the

twin propellers broke. The machine fell from a height of about 60 feet.

Selfridge was killed and Orville broke a thigh. That was the first

aeroplane fatality.

CHAPTER

2

EARLY FLYING IN EUROPE

The official mind—first

seaplane—Gordon Bennett Race—Santos Dumont—first records—Moore-Brabazon—Cody—Gnôme Motor—a painful airlift—A. V. Roe—first hour flight in

Britain—Aero Club makes flying rules—accident investigation—London to Manchester.

THE Wright Brothers carried on with their experiments. Although the

credit of having made the first flight goes to Orville, the general

impression which one received through the papers was that Wilbur, who

was about four years older than his brother, was the dominant partner.

Griffith Brewer said that they were a team who worked together. Each

flew as much as the other, and neither could be said to be more of an

originator than the other.

By 1907 the Wright biplane was a practical flying machine. An offer was

made to the British War Office. Haldane, who was then War Minister,

wrote in reply, "the War Office is not disposed to enter into relations

at present with the manufacturers of any aeroplanes." That was a

fitting preliminary to the state of the official military mind in

Britain and to the action of the War Office in 1912, when flying by

Territorial officers was disapproved; and an offer by Mr. (later Sir)

Frank McClean to lend two aeroplanes and provide instruction for such

officers, was refused.

Another ardent and successful experimenter in the United States, and

chief rival to the Wrights, was Glen Curtiss, who, in 1911, became the

first man to build an aeroplane which would take off from and "land" on

the water. In this connection I think it is better to use the word

"alight", for "landing on water" is surely a contradiction in terms.

The French use the terms "aterrisage" and "amerisage". Another

contradiction in terms, which is much used to-day, frequently by the

B.B.C., is the phrase "flying at a low height"; sometimes, to avoid

that, people say "at a low altitude", which is surely just as wrong.

"Flying at a low level" is more correct.

For many years till after 1914, nearly all aeroplanes flying in the

United States were either Wrights or Curtisses, though a number of

European aviators visited the States, mostly with French aeroplanes. In

the autumn of 1910, Claude Grahame-White, fresh from the fame gained

when he so gallantly lost the London-Manchester prize, won the Gordon

Bennett race for Great Britain, flying a Blériot monoplane driven by a

Gnôme motor at Belmont Park, New York. His successful rival

in the Manchester race, Louis Paulhan of France, had visited the States

in January 1910 with a Farman biplane and at Los Angeles had broken the

world height record by reaching 3,990 feet.

Meanwhile flying experiments bad been made in Europe on independent

lines from those of the Wrights. As we have already seen, Clement Ader

thought he had made hops in France as far back as 1897. Louis Blériot

had built his first aeroplane, a biplane, in 1900, and Captain Ferber,

who was killed at Boulogne in 1910 in what looked like quite a minor

accident, experimented about the same time. Alberto Santos Dumont, a

wealthy French-Brazilian, who had experimented with airships, early

turned his attention to aeroplanes. He had made twelve

airships by 1905 which made his name famous. His first successful

aeroplane, 14 bis, was a tail-first biplane, driven by an

eight-cylinder Antoinette engine, which he first "flew" on 13th

September 1906 for a few metres. On 23rd October the same year he

"flew" about 50 metres. That flight is generally considered to be the

first controlled flight in Europe. It was shortened by the presence of

some onlookers, and the pilot cut the motor to avoid accident. A Dane

named Ellerhammer has been said to have flown earlier, but in Denmark I

was told there was no proof of this.

A few weeks later, Santos Dumont asked the Aero Club de France to

observe and time his flights at Bagatelle. The result was the

confirmation, or "homologation" as it is bureaucratically and clumsily

called, of the first world records. One was "Distance en Circuit Fermé"

(distance in a closed circuit), though the circuit was by no means

"fermé" for it was a straight hop of 220 metres. The "flight" was timed

and a speed record was homologated of 41.292 km.p.h. (25.06

m.p.h.) [Note 3].

No modern

aeroplane could fly as slowly in 1950 except those of the helicopter or

autogiro types. Most of the experimenting and progress has been at the

other end of the speed range.

In those early days the Voisin brothers, Gabriel and Charles, had made

experiments, and produced a type of biplane with "side curtains"

between the main planes at each wing-tip. Several early pilots, notably

Henri Farman and Leon Delagrange, learned to fly on Voisins,

as also did a young Briton, J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, now Lord Brabazon,

holder of No. 1 Aviators' Royal Aero Club Certificate, who was

President of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, and the

R.Ae.C. in 1946.

About 1908 an American, S. F. Cody, long domiciled in England, who had

been experimenting in England with man-lifting kites and airships, was

experimenting with both lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air craft for

the British Army at Farnborough. He became a naturalised

British citizen during the first Doncaster flying meeting in England in

the autumn of 1909, at which meeting he flew his aeroplane.

In 1909 the Gnôme motor was invented by the

French brothers Séguin. This invention did more to advance aviation

than any single invention until the gas turbine more than thirty years

later. The Gnome was an air-cooled "rotary" motor. The crankshaft

remained stationary while the seven air-cooled cylinders revolved round

it. Stationary air-cooled motors of those days suffered from

overheating because the aeroplanes were so slow there was not a strong

enough airstream to cool them. The water-cooled motors were very heavy.

The 50 h.p. Gnôme, which only developed about 35

h.p., was much lighter per horse power than any contemporary motor.

Henri Farman first "put it on the map" when he flew 180 kms. non-stop,

round and round a pylon course at the first Rheims Meeting in August

1909. For many years after that most of the epoch-marking flights were

made on aeroplanes powered by Gnôme motors of 50, 70, 80, 100, 140

or 160 h.p. The 100 h.p. Gnôme was called a "mono-soupape"

(one valve). It was on a semi-sleeve valve principle. It was often used

as the power-plant for the Avro 504k. That aeroplane is affectionately

remembered as the "Mono Avro" and was one of the most successful

trainers for many years after 1918.

The Gnôme had its defects. It would only

run at almost full throttle; it used as much oil as petrol; if the

inlet valve broke, as it often did, the motor caught fire. But it was

lighter and more reliable than its contemporaries.

The Army had become interested in Cody's aerial experiments through a

successful man-lifting kite at Farnborough. These kites he sometimes

flew from the football ground of the Crystal Palace. It was in one of

those kites that I first became airborne about 1903. As a small boy of

about nine, I went into the Palace grounds on my way home from school

to watch Cody. I pestered him with questions, which he always answered.

I often asked him to let me have a "kite ride" in the basket, for I was

not then old enough to have more sense.

His method was to fly several kites in a team, on a single wire rope or

cable. If the wind was strong enough to give a good pull, a

"pilot-kite" with a basket in which a man could stand, was sent up the

"string" for several hundred feet. Its ascent or descent was controlled

by inclining the angle of the kite. One day, to my great joy, Cody told

me I could have a "little lift". He put me in the basket, which had a

cord attached to it, and I was allowed to go up about ten or twelve

feet. It seemed far higher than that to me, and I boasted to my school

friends that I had been to "a terrific height". I boasted too much, for

one of my school masters heard me. The result was that I was bent over

the table and given "six of the best", which was an early example to me

of the dangers of careless talk!

A. V. Roe, too. was experimenting at Lea Marshes, then an unfrequented

spot in the outskirts of east London. He built a triplane.

Moore-Brabazon had brought a French Voisin to England with which he

flew for gradually extending distances. When the Royal Aero Club held

an enquiry in the nineteen-twenties as to who made the first flights in

Great Britain, they decided, on the evidence, that he had the prior

claim.

Twenty years later, A. V. Roe was being remembered as a pioneer. He had

not yet been knighted. This appeared in the Evening News on 8th June

1928:

AIRMAN WHO WAS BELIEVED INSANE!

MR.

ROE'S TRIP 20 YEARS AGO TO-DAY

ARREST THREAT

By Our Air Correspondent

Twenty years ago to-day—on June 8, 1908—Mr. Alliott

Verdon Roe made the first flight on a heavier than air machine in Great

Britain. All the aeronautical world is attending a great gathering in

his honour to-night at the Savoy Hotel. The Duke of York will attend.

Mr. A. V. Roe came to Brooklands in

1908 with a curious stick-and-string pusher-tail-first biplane driven

by a 27-h.p. engine. After many weeks of hard work and heart-breaking

efforts to fly, the machine was at last coaxed into the air and

actually flew—that is to say, it got off the

ground and continued its progress without loss of speed—for a distance

of 60 yards at a height of one yard.

At the time that Cody was experimenting with his kites at the Crystal

Palace, the usual Bank Holiday balloon ascent was not billed. I

remember telling people that, instead, a man would go away in a kite.

It seemed to me a most natural development that a captive kite could

become mobile, as could a captive balloon! Perhaps I was "dreaming

tendentiously" of sailplanes!

There had been a few experimenters with aeroplanes in Great Britain

before the end of 1908, but 1909 was the year in which flying really

began in this country. A. V. Roe had made a few flights or hops, first

at Brooklands and later at Lea Marshes, but there is no real evidence

to show that they were "sustained" flights.

S. F. Cody, whose early experiments with man-lifting kites have already

been mentioned, had made some flights of a slightly longer duration,

which were probably the first real flights in Great Britain. But Cody

was still an American citizen at the time.

J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon had been making some flights towards the end of

1908 in a Voisin biplane with a Vivinus motor at Issy-les-Moulineaux,

near Paris, and he brought that aeroplane to Eastchurch early in 1909.

On that machine he made sustained flights, and to him must go the

honour of being the first Briton to fly in Great Britain. "Brab" had

also been a racing motorist and an early balloonist. When he was at

Cambridge he went ballooning. When he was questioned by authority about

a late return to college, his answer that he had been ballooning was

hardly believed, but was accepted as a novel

excuse.

Just before Blériot flew the Channel on 25th July 1909, A. V. Roe had

received a summons for causing public danger with his flying

experiments on Lea Marshes. He had been long treated as an object of

derision, and his sanity was even questioned. But when Blériot had flown the Channel, and had

proved that aeroplanes were practical propositions, the authorities

felt that it might be their sanity which might be questioned if they

proceeded, so the summons was dropped. Sir Alliott Roe, as he became,

told me how, instead of the expected arrival of minions of the law, a

deputation of honour was sent by the local authority to watch him fly.

On 14th May 1909, Cody made a flight of a mile at Laffans Plain,

Farnborough. He reached a height of 30 feet. That flight was described

as "a new record for Great Britain". His aeroplane was then fitted with

an E.N.V. motor of 80 h.p. In August he was making circuits of Laffans

Plain. By the end of August 1909 Cody had logged a cross-country flight

of nearly 10 miles in the Farnborough district. On 8th September he

flew for 1 hour 3 mins. during which he reached a height of more than

600 feet; he covered about 40 miles. But Cody was not then eligible to

enter for the Daily Mail

£1,000 prize for the first circular flight of a mile by a British

subject on a British aircraft.

One of Cody's young assistants about this time was a youth named Duncan

Davis. He is that same Duncan Davis who founded the Brooklands School

of Flying, which was one of the mainstays of private flying between

wars. When the war was over in 1945, and flying clubs were beginning to

get into their stride again, Duncan was once more one of the most

active executives. He brings to the flying club movement some of that

tremendous and unquenchable optimism and enthusiasm of the early

pioneers. When the clubs were facing great difficulties and the

government of the day refused to re-introduce subsidies after the war,

Duncan, at a gathering of the Cinque Ports Flying Club at Lympne said:

"Flying Clubs will carry on regardless . . ."

When Santos Dumont had made the first flight in Europe in October 1906,

Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the Daily Mail, offered

a prize of £1,000 for the first person to fly across the English

Channel on a heavier-than-air machine, and £10,000 for the first flight

in a similar type of machine from London to Manchester. Other

newspapers, not so far-sighted, ridiculed the offers, and one offered a

prize for the first flight to the moon. Such a journey, if not actually

an aerodynamic flight as at present understood, could not be ruled out

as a possibility to-day.

Cody announced his intention of making an attempt on the London to

Manchester prize in September 1909. He later announced that he would

make a definite attempt on 9th October, but motor trouble compelled him

to abandon the flight.

The success of the Rheims flying meeting in August 1909 was

so great that meetings were soon planned for England. The

Lancashire Aero Club, which was formed in 1909 (as also was the Midland

Aero Club), obtained the necessary support to hold the first British

flying meeting at Blackpool. The Club received the sanction and

approval of the Aero Club, which was the body recognised in Great

Britain by the

Fédédération Aéronautique

Internationale

(F.A.I.). A meeting was also announced for the same week, 18th October

1909, by the Doncaster Corporation. The Aero Club refused to approve

the Doncaster meeting, and threatened to suspend the Aviators

Certificates of any pilots who took part in competitive events there.

Such suspensions meant that the pilots would not be able to take part

in aviation meetings sponsored by the F.A.I. in any part of the world.

This action led to considerable feeling, but the Club was adamant, and

thereby greatly increased its prestige as the controlling body for

sporting flying in Great Britain, a position which has never been

seriously challenged since. The Club from now on began to exercise its

authority over private and sporting fliers. There were no laws or

inhibitions against flying, even dangerous flying. So the Aero Club

made certain rules against low flying over cities or crowds, penalty

for the contravention of which would be suspension of the aviator's

certificate. Such suspensions were made, notably against Douglas Graham

Gilmour for low flying over the crowds at Henley Regatta in 1911. The

same pilot incurred the Club's displeasure, though not suspension, by

flying over the Oxford and Cambridge boat-race in 1911, the first

occasion on which an aeroplane flew over the race. A French pilot,

Brindejonc des Moulinais was suspended for passing over Central London

when on his way from France to Hendon to compete in an air race. His

suspension by the Royal Aero Club caused a certain amount of ill

feeling between the Club and the Grahame-White Aviation Company, who

operated Hendon aerodrome, but Brindejonc was not allowed to compete in

the race for which he had flown from France. Douglas Gilmour, too, was

not allowed to compete in the Circuit of Britain in July 1911 because

of his suspension. There is no doubt that the strong action by the

Royal Aero Club did much to check any tendency towards flying to the

danger of the public, and may well have delayed the coming of

frustrating legislation in those early days of growth.

Very soon after the first fatal accident in Britain, to the Hon. C. S.

Rolls in 1910, the Royal Aero Club set up a committee to investigate

all fatal accidents. [Note 4].

They were even able to get power to investigate accidents to aircraft

of the Army and Navy. The findings of this committee were most valuable

in preventing further accidents from what might otherwise have been

unexplained causes. This accident investigation committee was the only

such body in Great Britain, until the Services set up their own

enquiries into accidents during the War of 1914-1918.

On 30th October 1909, J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon won the Daily Mail prize of

£1,000 for the first British aviator to fly a circular mile on an

all-British machine with British motor. He flew a biplane designed and

built by Short Bros. with a 50 h.p. Green motor. He made that historic

flight at the Aero Club flying ground at Shellbeach close to Eastchurch.

Early in 1910, a young Englishman, Claude Grahame-White, had been

learning to fly in France. He first took a course at the Blériot

school, and then went to learn biplane technique at the Farman school.

He qualified for his French Aviators' Certificate in March 1910.

A pilot, in those days, could learn to fly one month and the next month

be in the public eye as a "famous and intrepid airman." That happened

to Grahame-White. As soon as he had qualified at the Farman school, he

bought a Farman blplane with a 50 h.p. Gnôme motor, brought it to England

and entered for the Daily

Mail London to Manchester prize. Farman had also designs

on the prize, for which he intended to enter his test pilot, Louis

Paulhan. As Grahame-White had learned at the Farman school, and had

bought a Farman, Henri Farman promised him that he (Grahame-White)

should have a week's grace so that he could start before the Farman

entry.

Grahame-White took his Farman to Park Royal from which place he

intended to start. The rules said that the aeroplane must pass (in

flight) a point within five miles of the Daily Mail offices in both

London and Manchester. Grahame-White intended to pass the gasometer at

Willesden Junction which would bring him within the 5-mile radius of

London. The rules also required the flight to be accomplished within 24

hours, and with not more than two intermediate stops.

He left Park Royal at 5.15 a.m. on a cold and blustery morning. He

rounded the gasometer, on which Harold Perrin, Secretary of the Royal

Aero Club, was standing as official observer, at 5.30 a.m. Perrin

hurried down from the gasometer and was taken in a R.Ae.C. official car

to follow the aeroplane. Grahame-White followed the London and North

Western Railway from Willesden to Rugby where he landed at 7.20 a.m.

The car, bringing Perrin, arrived at Rugby 10 minutes before the

aeroplane! After a short rest, Grahame-White restarted. The wind, by

then, had increased considerably.

He now found that his Gnôme motor was not running as

sweetly as it had run earlier, and he suspected weak valve-springs. So

he landed at Hadmore Crossing, near the railway between Whittington and

Tamworth, near Lichfield. He had intended to restart in the dark at

about 2 a.m. the next morning. But the increasing wind made that

impossible. He decided to abandon the flight for the

prize that time, and to fly on to Manchester. From there he

intended to make the flight in the reverse direction in the hopes of

beating Paulhan, who would be ready to try for the prize on the

following Wednesday.

Grahame-White had given orders for the machine to be securely pegged

down. But those orders were not fulfilled, and during the Sunday

afternoon the biplane was blown over by a gust and was severely

damaged. It was taken back to London and was quickly repaired. An

aeroplane of those days, with simple construction, could be almost

completely rebuilt in a fortnight. The machine was taken to Wormwood

Scrubs, where it was housed in a big airship shed, and it was ready

again on Wednesday morning, 27th April. Paulhan had arrived at Hendon,

and was ready to start from the spot which later became Hendon

aerodrome. George Holt Thomas, who had acquired the British Farman

agency, sponsored him. Still another Frenchman, M. Dubonnet, had also

entered for the prize with a Tellier monoplane. The week's notice which

each competitor had to give, would expire on 2nd May. So Paulhan and

Grahame-White still had the field clear until then.

Paulhan left Hendon at 5.21 in the afternoon of 27th April. Conditions

were far from ideal, a gusty wind was blowing. At Wormwood Scrubs,

Grahame-White had tried to test his rebuilt aeroplane about 2.30 p.m.,

but found the crowd prevented him, so he went to bed in a nearby hotel

to get some much-needed rest. He was asleep when the news arrived that

Paulhan was flying for Manchester, and had passed Hampstead Cemetery

where he was officially observed to have passed within the five-mile

radius of London. Paulhan passed over Rugby at 7.20 and landed at 8.10

in a field near the Trent Valley station, Lichfield, 117 miles from

London.

Meanwhile Grahame-White was awakened, and his Farman was hurriedly

prepared. The wind was still gusty, but he started in pursuit of

Paulhan at 6.29 pm. Gathering darkness forced him to land near the

railway at Roade, near Northampton, 60 miles from London.

Then followed the most dramatic incident of the whole affair.

Determined to beat Paulhan, Grahame-White decided to restart in

darkness, early the next morning. The small field in which he had

landed was illuminated by the head-lamps of cars, and at 2.50 on the

morning of 28th April 1910 Grahame-White started. This was the first

night-flight on record. But the wind was still strong, and at

Polesworth, 107 miles from London, he was over broken country where

wind eddies forced him down.

Paulhan restarted from Lichfield at 4 a.m. and reached his goal at 5.32

when he landed at Didsbury. Thus he made the journey in an elapsed time

of just about 12 hours. His flying time was 3 hours 47 minutes for a

distance of approximately 185 miles. The flight was the first serious

cross-country city-to-city flight ever made in Britain. The race

between the two pilots aroused very great interest throughout the

country, and, indeed, throughout the whole civilised world.

Grahame-White, the young and inexperienced aviator, caught the popular

fancy, and people realised that the match was between experience and

youthful enthusiasm. The flight did much to make people in Great

Britain realise that aeroplanes were on the way to becoming practical

vehicles of travel. As one who was present at Wormwood Scrubs that

famous day, I can never forget the excitement and enthusiasm, specially

when the news came through of Paulhan's departure. I was a boy of

sixteen, and my companion was Cyril Holmes, who later became one of the

first pilots on the London-Paris service, and who now, in 1950, manages

Bristol flying school. When we returned to Victoria we saw the crowds

waiting to see King Edward VII, who died a fortnight later, return,

ill, from Biarritz. Lord Northcliffe had offered this Daily Mail prize

for a flight from London to Manchester because he realised that it was

between such cities that air travel could reduce the time for the

journey.

Yet in 1950 there was no air service linking the two towns. When I

wanted to go from London to Manchester and back in the day, I had to

leave my home in Chelsea at 7.45 a.m. to get an 8.35 train from Euston.

That train did not reach Manchester till 1.15 p.m. I spoke to

businessmen on the train, who told me they would use an air service if

there were one. It should be possible to leave the British European

Airways air station in Kensington at 8 a.m., be at Northolt at 8.30,

take off at 8.45 and reach Manchester Airport at 9.45, and be in

Manchester centre by 10.30, thus saving nearly three hours on the

train. When B.E.A. have their helicopter service in operation it should

be possible to go between London and Manchester in 1½ hours.

Peter Masefield, the able and enthusiastic chief executive of B.E.A.,

told me in 1950 that he has the London-Manchester service well in mind.

It was tried under the previous management of B.E.A. in the winter of

1947, when B.E.A. were not as safe and reliable as they have since

become, and was not then successful. The public did not patronise it

but I am sure they will when the new spirit of B.E.A. has had more time

to manifest itself.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the flight, Louis Paulhan, aged

67, was flown, on 27th April 1950, from London Airport at Heathrow to

Ringway, Manchester in a Gloster Meteor 2-seat jet trainer, in 38 mins.

The Meteor flew over the Daily Mail London office and from there to the

Manchester office in 24 minutes. The return flight between the two

offices was made in 19 minutes.

CHAPTER

3

THE BALLOON GOES UP

"The City of York"—Aero

Club founded—first secretary—Harold Perrin—Royal Aero

Club—early growth—Mossy Preston—later growth—Aviation Centre.

ON 24th September 1901, a balloon, City

of York, ascended on a fine afternoon of late summer from

the Crystal Palace carrying as passengers Frank Hedges Butler, his

daughter Miss Vera Butler, and the Hon. C. S. Rolls. Percival Spencer

was employed as professional aeronaut. At a height of 5,000 feet over

the Kentish suburbs the formation of a club to control the sport and

science of ballooning was suggested by Rolls. When the balloon landed

in Sidcup Park the Aero Club was in being.

Frank Hedges Butler later became chairman of the Aero Club, and was

largely influential in gaining the Royal patronage in 1910 when the

Club assumed the title of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom.

Miss Butler became Mrs. Iltid Nicholl, and Charlie Rolls became, with

Henry Royce, the co-founder of the famous firm of Rolls-Royce Ltd. In

1910 Rolls became the first Englishman to fly the English Channel, the

first to cross it each way, and was the first Englishman to lose his

life in a flying accident. He was killed at Bournemouth flying meeting

in 1910. His portrait was presented, on my suggestion to Rolls-Royce,

to the R.Ae.C. in 1950.

I am fairly sure that I saw that famous balloon ascent, but I did not

realise that I was witnessing the foundation of something which would

become so influential. Why I remember the ascent was that at the end of

September 1901 I was starting my first football term at school at

Sydenham just outside the Crystal Palace. The City of York passed

over us quite low, and a boy, who had an American mother, argued with

us that the balloon was the City

of New York and therefore must be an American balloon. The

rest of us would not stand for that Yankee boasting, so we made quite

sure that the name on it was the City

of YORK, and then we rolled the American boy in the mud!

The Aero Club, in its first youth, was given the use of two rooms in

the Automobile Club, which acted as parent, in their premises at 119

Piccadilly, to which the Royal Aero Club returned 30 years later as

full tenants of the whole building, by then considerably enlarged. The

Aero Club was registered at Somerset House [Note 5]

by the secretary of the Automobile Club, Claud E. Johnson, who, with

Rolls and Royce, was the third founder-director of Rolls-Royce Ltd.

The

first secretary was E. O. Pope. The secretaryship of this new and

insignificant little club was then only a part-time job, and carried a

"salary" of £2 per week. Mr. Pope remained as secretary until 1905, by

which time the Club had moved into a small suite of rooms in a block of

offices at 110 Piccadilly, where the Park Lane Hotel now stands.

When

Pope resigned, a young man who had been experimenting with models of

aeroplanes, was offered, and accepted the job of secretary. His name

was A. V. Roe, who had not then begun to experiment with full-sized

aeroplanes. He was at that time working with a firm in Jermyn Street,

which was building a helicopter type called the Davidson Gyropter. Sir

Alliott told me later that he did not think he started any actual

secretarial work; because a fortnight after he had been appointed, he

was sent by his firm to America to obtain certain parts for the

Gyropter.

Roger Wallace, the first chairman of the Club,

suggested a young and energetic man, whose name was Harold Perrin, for

the job. Perrin, who was the first really effective secretary, remained

until his retirement at the end of 1945, having seen the Club rise to

become one of the biggest, most influential, and best in London. He

died on 9th April 1948.

In 1906 the Aero Club moved from 110 to

166 Piccadilly, to a suite of rooms on the second floor of a building

facing Bond Street. There they were housed in more comfort and, for the

first time, social amenities, such as a lounge, bar, and snack bar were

added.

There they were overtaken by the coming into being, as

practical propositions, of power-driven aeroplanes. They were there,

too, when the war broke out in 1914, and the aeroplane, after being

little more than a plaything with only a sporting use, became a weapon

of war. Most members of the Club were active pilots, designers, or

balloonists, and they joined the R.F.C. or the R.N.A.S., or else turned

to the very important job of designing and building aeroplanes, aero

motors, airships, or observation balloons. Perrin joined the R.N.V.R.

and became a Lt.-Commander. An assistant secretary was engaged, B.

Stevenson, who was so well-loved as "Steve". A previous assistant to

Perrin, named Joseph, did not remain long. For a short time, in 1909

there was a joint Secretary, with Perrin, named Claremont, a retired

naval captain.

While at 166 Piccadilly, the Club received Royal

patronage, largely through the efforts of Mr. Hedges Butler, who had

become chairman, and it became the Royal Aero Club of the United

Kingdom. That was in February 1910.

By the end of 1915 many

people had learned to fly in the Services, and the Club, besides

acquiring a large number of new members, had issued nearly

3,000

Aviators' Certificates at one guinea each. The premises at 166

Piccadilly had now grown too small to house the Club, and so at the

beginning of 1916, premises were taken at 3 Clifford Street, and the

members had the first real home of their own. It had at first been

intended to take another floor at 166 Piccadilly, but the whole of 3

Clifford Street, off Bond Street, was rented for less money than the

two floors in Piccadilly and was far more suitable in every way. On the

ground floor was a spacious entrance hall, which some years later

became the lounge. In the basement was a billiard room. On the first

floor was a cosy bar, with a library leading off it, and with the

secretary's office next door. On the floor above were two dining rooms

which between them would seat at one time about 30 members. Really good

breakfasts, lunches, teas, and dinners were now served, and the Club

began to gain the high reputation for cuisine which it still has.

The

first big task which the Club had to do after the war was to organise

the Schneider Trophy contest for 1919. The contest had been won in 1914

by Great Britain.

At big flying meetings in Britain, the Club

was entirely responsible for the organisation, and the very successful

parties at one or other of the local hotels where all the competitors,

officials, journalists, and others were staying. Those flying occasions

were just what were needed to weld the aeronautical community into the

"flying family" into which it developed during the 1920-30 period. That

family atmosphere is still very much in evidence, though it is not now

quite so intimate as it was in the Clifford Street days.

In 1926

the Club extended its sphere of influence by its successful formation

of the Light Aeroplane clubs throughout Great Britain. After the

1914-18 war, the Club bought a few Avro 504k biplanes which were kept

at Croydon. Members could hire these at a very reasonable cost. When

the Light Aeroplane Clubs were formed, the Royal Aero Club ceased to

own aircraft itself. After 1926, the light aeroplane movement steadily

expanded, slowly at first, but with ever-increasing momentum. That very

naturally led to the steady growth of the Royal Aero Club. British

victories in the Schneider Trophy Contests in 1927-29-31 added to the

Club's prestige.

About the time of the last contest in September

1931, the Club moved from its home at Clifford Street to 119 Piccadilly

where it had its first "landing place" in 1901. For some time 3

Clifford Street had been becoming too small and crowded to house, with

any real comfort, the great accession of strength which had come in the

form of greatly increased membership. Several buildings were inspected

by the House Committee before the decision was made to take 119

Piccadilly. A large house in Curzon Street and another in Carlton House

Terrace were considered. When they first came to Piccadilly from

Clifford Street the spacious building, which had been taken

over from the Cavendish Club, looked very big, and it seemed

as

though they would never fill it. There were far more amenities, many

more bedrooms, and a squash court. Membership steadily increased. When

the war ended in 1945, the Club became so full that there was, for the

first time, a waiting list for membership.

At the end of 1945,

Harold Perrin retired. He had steered the Club from the tiny gathering,

which had two rooms in 1905 when he became secretary, to the

influential body it became. It would be difficult to exaggerate what

"Harold the Hearty" (as he was known to his many friends) had done to

help bring the Club to the high position which it now holds, not only

in British, but in international sporting flying. From the earliest

dnys he organised, helped to organise, or was present at almost every

big aviation occasion. Like all strong characters he made many enemies,

but they must have been well outnumbered by his friends. When he

retired, he appeared among us rather in the role of an elder statesman,

always assured of a welcome wherever he went. He was succeeded in

January 1946, by Colonel Rupert Preston, known to all as "Mossy", who

had joined the Club in 1924 when he was a young subaltern in the

Coldstream Guards. People often ask why an army officer was chosen as

secretary-general, rather than an officer from the R.A.F. The reason

was that the Committee considered that he was the most suitable man for

the job.

Between the wars the Club had done much to foster

the growth of private flying, as well as Club flying. As the

representative of the F.A.I. in Great Britain, customs carnets were

issued by, and only by, the Club, so that aeroplanes used for touring

could be flown in and out of this and other countries without having to

pay duties, if they were not intended for sale. In 1929 the Club had

not developed enough to be in a position to run a touring department of

its own, so an arrangement was made with the Automobile Association.

The A.A., through its own touring department, provided maps for aerial

tourists who wished to go abroad, and planned routes for them. When the

war ended in 1945, the A.A. were not anxious to go on with that

arrangement.

The Council of Light Aeroplane Clubs, which had

been formed in 1930 to co-ordinate the work of the clubs, and to

exchange information among clubs, was disbanded at the end of 1945. In

its place the Association of British Aero Clubs was formed. The term

"light aeroplane" was dropped because the low-powered aeroplane had

"grown up", much as in the early days of motoring the "light-car" had

grown up, and is now almost non-existent.

The

A.B.A.C. at once

got to work and concluded an arrangement with the Ministry of Civil

Aviation to get certain aircraft such as Tiger Moths, Austers, and

Proctors, which were surplus to Service requirements, and make them

available to the clubs which were members of the A.B.A.C. The

Royal Aero Club also strove very hard to get reduced the exorbitant

landing fees, which were imposed on small aircraft which landed at

state-owned airfields.

Another

innovation by the Committee was to introduce associate membership. Many

men and women wish to join the Club in order to be able to use the

touring facilities, and the various sources of information which are at

the Club's disposal. Many do not live in London, and so do not wish to

join as full members and pay the necessarily high annual subscription.

On

21st June 1946, the associate membership plan was first announced.

Associate members now pay £2 2s. annually for which they get all the

advantages of full membership, except that they cannot use the Club

premises in Piccadilly. It was decided to house the aviation

departments in a separate building. First of all a building near

Victoria Station was chosen, but the Ministry of Health decided that

they needed it for their re-housing programme. Then another building in

Sloane Street was sought, but negotiations fell through.

Lord

Londonderry, who before the war had been a most able and enthusiastic