BRITISH TEST PILOTS

GEOFFREY DORMAN

A. R. Ae. S.

First published 1950 by Forbes Robertson Ltd.

© Geoffrey Dorman 1950

Cover image courtesy of Paul Slater

Editor's notes

This book was published in 1950, less than a half century after the

Wright brothers' first powered flight. Between those dates the pace of

aircraft development was astonishingly rapid, partly accelerated by the

military demands of two world wars, the latest jet aircraft a sharp

contrast in design and performance to the flimsy Wright Flyer of 1903.

Experimental aircraft had already broken the sound barrier.

Included

in this illustrious group of men (no women in those days devoid of

gender equality!) is John Moore-Brabazon. Author Mr Dorman

notes

that

although 'Brab' was not technically a test pilot he merits inclusion as

the achiever, in 1909, of the first authenticated powered flight in

England by a British subject. Indeed his pilot's certificate number was

1.

The group also includes record breakers: Group

Captain Edward Donaldson set a new world air speed record of 616 m.p.h.

in September, 1946 flying a Gloster Meteor Mk. 4. Roland

Beaumont and

John Derry were the first British pilots

to exceed the speed of sound (in the USA and in the UK respectively). After this book was published

Neville Duke in September 1953 set a new record of 728 m.p.h. flying a

Hawker Hunter. In March 1956 Peter Twiss again broke the record,

raising it to 1,132 mph in the Fairey Delta 2 research

aircraft.

John Lancaster was

the first pilot to eject from a British

aircraft during an in-flight emergency by

deployment of the Martin-Baker

ejection seat. He eventually lived to the age of 100 years.

We have been unable to trace the current copyright owner(s) of this

book.

If the owner(s) object to its availability on the Steemrok website,

please write to comms@steemrok.com and the file will be removed without

delay.

Julien Evans

Editor

Steemrok Publishing

steemrok.com

THIS IS REAL TEST FLYING

In

his book "Jet flight", John Grierson, who was one of the Gloster team

of pilots who tested the very first jet aircraft, wrote this of a test

flight by Michael Daunt on 5th March, 1943. It gives a good insight

into test flying.

"Quite a lot had happened—a

successful take-off had been made, an out-of-balance nose-wheel

detected, serious unpleasant directional instability had been

encountered and experimented with in an effort to trace its

origin, a safe landing had been effected and a fault had been detected

in the undercarriage shock absorption. All this was

obtained as

the result of a flight with a duration of just three and a half

minutes! This is real test flying, when the pilot notes everything that

is happening and is able to render a story, not only coherent but

constructive, on landing."

To all keen airminded boys and young men—especially those of the West

London Aviation Club—hoping

that they too, like these test pilots, will have sufficient keenness to

press on regardless and so attain their objective of becoming pilots.—G.D.

MY

OBJECT in writing this book is to put on record something about the men

of Britain who have tested the British aeroplanes immediately after the

World War of 1939-45. This has been the period of greatest

change

and progress since the start of aviation nearly 50 years ago, for it

has seen the beginning of practical jet-propelled aircraft—fighters, bombers, and airliners.

Possibly

aeroplanes such as the Comet tested by John Cunningham and the

Swift tested by Mike Lithgow, will, in the not very distant future, be

looked on by a new generation as "funny old sub-sonic crates with those

old-fashioned wings"! Some of my subjects in this book can

remember testing biplanes which, in their day, were considered

as

being "super" just as were the Comet and Swift in 1950.

This

book has been possible only by close co-operation between the test

pilots and me. I have often extracted the information with great

difficulty at first. Some test pilots are about as easy to pin down to

a date as quicksilver! Once they realised what I was trying to

do, they have one and all been most co-operative.

The older

ones were the easiest. They have lived and learned, and long ago they

learned that publicity, though few of them like it, is a

necessary

evil which cannot be avoided!

The opening gambit of about two

thirds of the pilots, when I first told them what I wanted, was "Well,

there is nothing very exciting or out of the ordinary about my life". I

got to know this by heart!

In every case the younger ones were

the most difficult, and for entirely praiseworthy reasons. Apart from

the fact that they did not want to be accused by their fellows of

"line-shooting", they felt that they had been flying for such a short

time compared with Mutt Summers, Harald Penrose, or R. T.

Shephard, who have been testing since the 1920s, that they could not

possibly have had experiences which would interest anyone. It was only

when I persuaded some of them to talk informally over a glass of

something or to try and put a few notes on paper, that they realised

that even they, babes as they were by comparison, had lived interesting

lives.

As to being accused by their fellows of "line-shooting”,

I was able to assure them that they would "all be in the dog-house

together".

All

pilots of whom I have written are now my very good friends, and I have

flown with most of them. Some of the older ones I have known for years;

I am extremely proud now to number the younger ones among my new friends—good

types, but in spite of this, I still talk to all test pilots

with

a certain amount of awe and respect, for as one of the most ham-handed

of pilots, I have a real and tremendous admiration for their knowledge

and skill.

The "gang" of whom I write cover a wide range, and represent a real

cross-section

of life. One, who is now over 50, was a pilot in the R.F.C. in 1916; he

still flies 600 m.p.h. jet fighters. Another was a boy cadet in the Air

Training Corps during the last war.

There was one in whom I took

a special feeling of pride. Some years ago he was a telegraph boy. I

formed a flying club for those boys, and to get on easy terms with

them, I had myself fitted out with telegraph boy’s uniform. The biggest

boy was told to give me his uniform, which formed a bond of friendship

between us which existed till his death in June, 1950. When an aircraft

manufacturer offered to teach one of my telegraph boys to fly, I chose

the one whose uniform I had inherited. On such irrelevant trivialities

careers turn, for before that Jeep Cable had no thoughts of flying. He

became chief helicopter test pilot to the Ministry of Supply.

Another

of these pilots was a London policeman in the blitz. He transferred to

the Fleet Air Arm because he found a "copper's" uniform too hot in

summer!

All were boys of great determination, and their success

in getting into flying, often against great odds, should be examples to

boys reaching their adolescence. Many of them were Fighter

Boys

who helped to save the world in the Battle of Britain, or Bomber Boys

who helped to pulverise Germany. Most of them have taken part in events

which stirred the world at the time.

It has been interesting to

find what caused them to take an initial interest in flying, and how

pioneers such as Sir Alan Cobham, who toured Britain with an "air

circus" brought flying at first hand to many boys who are now

test

pilots.

I have included the first of them all, J. T. C.

Moore-Brabazon, who is now Lord Brabazon of Tara, who has written an

introduction to this book. When he first flew in 1908, every flight was

a test flight!

Some of these have appeared serially, in

dehydrated form, in the Air

Reserve Gazette, Wings

(S. Africa),

Canadian Aviation,

and White's Aviation

in New Zealand.

I would

like to give full credit to John Yoxall of Flight, for giving

me the

idea. Some years ago he wrote a rather similar series in Flight of

which he is the art editor. I thought they were some of the most

interesting aviation articles I had ever read. I was extremely

disappointed when John concluded his series. As I was most anxious to

go on reading about the current series of test pilots, the only

solution seemed to be to write them myself. And this I have now done

with John Yoxall’s blessing.

To the victims, the test pilots themselves, my thanks for being so

patient with me.

GEOFFREY DORMAN.

30 Redburn Street, Chelsea, London, S.W.3. 1st November,

1950.

CONTENTS

Click on the blue dots  to access the various chapters directly

to access the various chapters directly

Dedication

Dedication

Preface

Preface

Introduction by the Rt. Hon.

Lord Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.

Introduction by the Rt. Hon.

Lord Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.

J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, now the

Rt. Hon. Lord Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.; the first of them

all

J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, now the

Rt. Hon. Lord Brabazon of Tara, P.C., M.C., F.R.Ae.S.; the first of them

all

R. P. Beamont, D.S.O. and Bar,

D.F.C. and Bar, D.F.C. (U.S.A.), A.R.Ae.S., English Electric

Co. Ltd.

R. P. Beamont, D.S.O. and Bar,

D.F.C. and Bar, D.F.C. (U.S.A.), A.R.Ae.S., English Electric

Co. Ltd.

T. W. Brooke-Smith, A.R.Ae.S.,

Short Bros. & Harland Ltd.

T. W. Brooke-Smith, A.R.Ae.S.,

Short Bros. & Harland Ltd.

G. R. Bryce, Vickers-Armstrongs

Ltd.

G. R. Bryce, Vickers-Armstrongs

Ltd.

F. J. Cable, A.F.C., Chief

Rotary Wing Test Pilot, Ministry of Supply

F. J. Cable, A.F.C., Chief

Rotary Wing Test Pilot, Ministry of Supply

Leslie R. Colquhoun, G.M.,

D.F.C., D.F.M., Supermarine Division, Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

Leslie R. Colquhoun, G.M.,

D.F.C., D.F.M., Supermarine Division, Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

R. M. Crosley, D.S.C., Short

Bros. & Harland Ltd.

R. M. Crosley, D.S.C., Short

Bros. & Harland Ltd.

J. Cunningham, D.S.O. and two

Bars, D.F.C. and Bar, de Havilland Aircraft Co.

Ltd.

J. Cunningham, D.S.O. and two

Bars, D.F.C. and Bar, de Havilland Aircraft Co.

Ltd.

John Derry, D.F.C., de Havilland

Aircraft Co. Ltd.

John Derry, D.F.C., de Havilland

Aircraft Co. Ltd.

Group Captain E. M. Donaldson,

D.S.O., A.F.C. and Bar, R.A.F. High-Speed

Flight

Group Captain E. M. Donaldson,

D.S.O., A.F.C. and Bar, R.A.F. High-Speed

Flight

Neville Duke, D.S.O., D.F.C. and

two Bars, A.F.C.,

M.C.(Czech)

Neville Duke, D.S.O., D.F.C. and

two Bars, A.F.C.,

M.C.(Czech)

George Errington, A.F.R.Ae.S.,

Airspeed Ltd.

George Errington, A.F.R.Ae.S.,

Airspeed Ltd.

E. Franklin, D.F.C., A.F.C., Sir

W. G. Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft

Ltd.

E. Franklin, D.F.C., A.F.C., Sir

W. G. Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft

Ltd.

A. E. Gunn, Boulton Paul

Aircraft Ltd.

A. E. Gunn, Boulton Paul

Aircraft Ltd.

H. G. Hazelden, D.F.C., Handley

Page Ltd.

H. G. Hazelden, D.F.C., Handley

Page Ltd.

Wing Commander J. A. Kent,

D.F.C. and Bar. A.F.C., A.R.Ae.S., Royal Aircraft Establishment,

Farnborough

Wing Commander J. A. Kent,

D.F.C. and Bar. A.F.C., A.R.Ae.S., Royal Aircraft Establishment,

Farnborough

J. O. Lancaster, D.F.C., Sir W.

G. Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Ltd.

J. O. Lancaster, D.F.C., Sir W.

G. Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Ltd.

P. G. Lawrence, M.B.E.,

A.R.Ae.S., Blackburn & General Aircraft Ltd.

P. G. Lawrence, M.B.E.,

A.R.Ae.S., Blackburn & General Aircraft Ltd.

M. J . Lithgow, Supermarine

Division, Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

M. J . Lithgow, Supermarine

Division, Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

G. E. Lowdell, A.F.M.,

Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

G. E. Lowdell, A.F.M.,

Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

H. A. Marsh, A.F.C.,

A.F.R.Ae.S., Cierva Autogiro Co. Ltd.

H. A. Marsh, A.F.C.,

A.F.R.Ae.S., Cierva Autogiro Co. Ltd.

J. H. Orrell, A.R.Ae.S., A. V.

Roe & Co. Ltd.

J. H. Orrell, A.R.Ae.S., A. V.

Roe & Co. Ltd.

A. J. Pegg, M.B.E., Bristol

Aeroplane Co. Ltd.

A. J. Pegg, M.B.E., Bristol

Aeroplane Co. Ltd.

Harald Penrose, O.B.E.,

F.R.Ae.S., Westland Aircraft Ltd.

Harald Penrose, O.B.E.,

F.R.Ae.S., Westland Aircraft Ltd.

R. L. Porteous, Auster Aircraft

Ltd.

R. L. Porteous, Auster Aircraft

Ltd.

W. B. Price-Owen, A.R.Ae.S.,

Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Ltd.

W. B. Price-Owen, A.R.Ae.S.,

Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Ltd.

H. A. Purvis, D.F.C., A.F.C. and

Bar, Civil Aircraft Test Section, Ministry of Supply

H. A. Purvis, D.F.C., A.F.C. and

Bar, Civil Aircraft Test Section, Ministry of Supply

Michael Randrup, D. Napier

& Son Ltd.

Michael Randrup, D. Napier

& Son Ltd.

R. T. Shepherd, O.B.E.,

Rolls-Royce Ltd.

R. T. Shepherd, O.B.E.,

Rolls-Royce Ltd.

R. G. Slade, Fairey Aviation Co.

Ltd.

R. G. Slade, Fairey Aviation Co.

Ltd.

J. B. Starky, D.S.O., D.F.C.,

Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Ltd.

J. B. Starky, D.S.O., D.F.C.,

Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Ltd.

J. Summers, O.B.E.,

Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

J. Summers, O.B.E.,

Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd.

L. P. Twiss, D.S.C. and Bar,

Fairey Aviation Co. Ltd.

L. P. Twiss, D.S.C. and Bar,

Fairey Aviation Co. Ltd.

G. A. V. Tyson, Saunders-Roe Ltd.

G. A. V. Tyson, Saunders-Roe Ltd.

T. S. Wade, D.F.C., A.F.C.,

Hawker Aircraft Co. Ltd.

T. S. Wade, D.F.C., A.F.C.,

Hawker Aircraft Co. Ltd.

Air Commodore Allen Wheeler,

O.B.E., Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough

Air Commodore Allen Wheeler,

O.B.E., Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations

Fatalities

Fatalities

The chapters have deliberately not been numbered, so that no one can be

alleged unlucky—or lucky—thirteen. For it will not be

known whether to start numbering from the introduction, or from

Moore-Brabazon or Beamont!

WE

ARE taught to-day that travel by aeroplane is entirely safe. I would

not for a moment dispute such instruction, but I reserve to myself my

own opinion on the subject, based as it is on a good deal of inside

knowledge, and will keep it to myself.

No one, however, will

dispute that new types are subject, shall we say, to "growing pains".

The intensity of these pains vary a good deal, from slight aches to

veritable spasms of agony.

Test pilots have the duty imposed on

them of taking, for the first time, into the air, the hopes

and

confidences of the designer. Of all people I think the test pilot will

agree that aeronautics is still not an exact science!

Faced with

a dazzling collection of dials, imposed upon a five manual organ, with

controls all in new positions, the first take off of a new type must be

what the French so well describe as a moment emotional.

When

your back is to the wall, many people are capable of very brave

actions. I count them as nothing to the bravery of the man who

deliberately steps into a new machine and for the first time unsticks

to prove it works.

These are tremendous people that Geoffrey

Dorman writes about. It is fit and proper that those who do these great

jobs should be appreciated, revered and known, and it is for

that

reason I commend, to all who are interested in the development and

perils of air, this admirable book.

BRABAZON OF TARA.

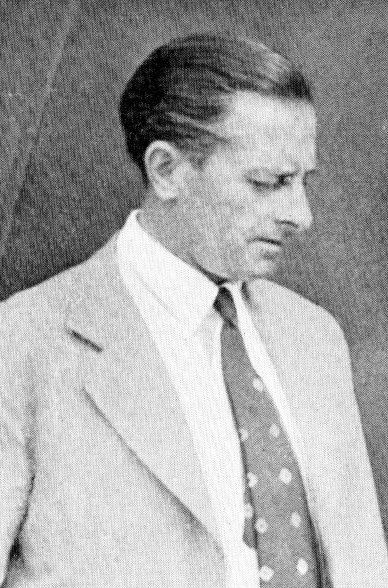

J. T. C.

MOORE-BRABAZON

The first of them all; now the

Rt. Hon.

LORD BRABAZON OF TARA, P.C.,

M.C., F.R.Ae.S.

I

START this book on the current series of British Test Pilots with

J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon very properly; for though he is now Lord

Brabazon of Tara, and so is no longer current as Moore-Brabazon nor as

a test pilot, he is, as I write this in 1950, happily as active as ever

in all other ways, and may he long remain so. He is one of the most

beloved, of many of the beloved pioneers who seem to be about as

deathless physically as they will always be in aeronautical history.

Brab,

as he is affectionately called by so many, was never quite a test

pilot, in the sense that phrase is used to-day, but when he

began flying in 1908, and during all his active life as a pilot, every flight

was indeed a test flight.

At the opening of the Twentieth

Century, well-off young men found outlets for their exuberant energy

and youthful high spirits in motoring and ballooning. One such young

man was John Theodore Cuthbert Moore-Brabazon, who was an undergraduate

at Cambridge with another young man in similar circumstances, the Hon.

C. S. Rolls, who later founded what is now the Royal Aero Club of the

United Kingdom, and Rolls-Royce Ltd. Charlie Rolls was Brab's closest

friend and between them they owned a balloon which they named Venus.

On

one occasion when the pair of them had been ballooning, returning to

College late, Brab explained to his tutor that he had been ballooning

and had been unable to get his train back to Cambridge. His tutor,

probably a bit sceptical, said that was the most extraordinary excuse

ever given to him for lateness!

Brab began motor-racing in 1903

and drove a big 120 h.p. Mors in a race on the sea front at Brighton,

and in many races on the Continent, winning the Circuit of the Ardennes

in 1907. He was at once attracted by the first aeroplanes of the Wright

Brothers, Santos Dumont, Farman, Blériot, and other pioneers. He went

to France in the latter part of 1908 and bought a big biplane, which

even then looked a bit clumsy, called a Voisin, made by two French

brothers, and he had learned to make short flights on it by the end of

1908.

The first picture on the first page of the first issue of Flight, January,

1909, shows Moore-Brabazon flying his Voisin in France at

Issy-les-Moulineaux in Paris.

Early

in 1909 he brought this Voisin to England and erected it at Shellbeach

in the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, where the Aero Club of the United Kingdom

(not Royal till 1910) had made a flying-ground with a club-house—the first flying club in

Britain! He had named his Voisin Bird

of Passage

and he began making short hops with it. On 2nd May, 1909, he made quite

a short flight of half a mile—a bit more than a hop—which was

recognised by the Royal Aero Club many years later, after careful

investigation of many claims, as being the first real authenticated

flight by a British subject in Great Britain.

I vividly remember reading each week in Flight and the Aero (the

predecessor of the Aeroplane)

of the flights made each week in the Isle of Sheppey by young

Moore-Brabazon. Even then he had the impish sense of fun, which has

developed so pleasantly, and is such a joy at any gathering at which

Brab speaks. There was a current phrase of those days, "Pigs might

fly", to suggest the fantastically impossible. Brab very soon debunked

that. He obtained a pig in a crate, and strapped it on the leading edge

of a biplane beside him with a notice on the crate, "I am the first pig

to fly", and he took it tor a short flight!

Being anxious

to start British aviation, he ordered a machine designed by Short Bros.

Ltd. with a 50 h.p. Green motor. It was very different from the Short

Solents which have been taking 39 passengers and six crew so

comfortably and spaciously through Central Africa, or the 1950

Shorts which Brookie Brooke-Smith and Mike Crosley test. On it he won a

prize of £1,000 offered by the Daily

Mail for the first circular flight of one mile by a

British subject on a British-built aeroplane with a British motor.

On

that aeroplane he also won the first British Michelin cup with a flight

at Eastchurch of 19 miles. Though this was officially the 1909 Cup, he

made the flight on 1st March, 1910, as the prize was not offered till

1st April, 1909, and was current for a year. As was usually the case

then, when performance increased measurably from day to day, the winner

made the flight in the last month of the competition!

He

continued flying until the middle of 1910, and when the Royal Aero Club

began issuing F.A.I. Aviators' Certificates, Brab was awarded No. 1 and

Charlie Rolls got No. 2. When Charlie Rolls was the first British

aviator to be killed, in July, 1910, in an aviation meeting at

Bournemouth, Brab retired from active flying as a protest against what

he described as the encouragement of dangerous circus tricks at flying

meetings.

During the 1914 war he joined the Royal Flying Corps

and was in charge of the development of aerial photography from the

beginning, ending that war as a Lieut-Colonel.

After that war he

entered Parliament as Conservative M.P. for Rochester, the home of

Short Bros. Ltd., and in 1923 was made Parliamentary Secretary to the

Minister of Transport. When in that office he acquired for

himself the very appropriate car registration number "FLY 1".

He

was made Minister of Transport in Churchill's Government of 1940 and at

the height of the Battle of Britain he was made Minister of Aircraft

Production in succession to Lord Beaverbrook. About that time he was

raised to the Peerage.

While he was Minister of Aircraft

Production he said, in a speech at a private dinner, that he thought it

would be of immense value to us that the Russians and Germans would now

be fighting one another, which would enable us to receive less

attention from Germany. That speech was viewed with grave displeasure

by the Communists in this country. Mr. Tanner raised the

matter at

the Trades Union Congress, and Brab was forced to resign from the

Govemment!

He is President of the Royal Aero Club of the United

Kingdom and President of the Royal Institution, Past President of the

Royal Aeronautical Society, and Past President of the Fédération

Aéronautique Internationale.

He gives his name to the Bristol

Brabazon airliner which was first tested in September, 1949, by Bill

Pegg, as recounted in the chapter on Pegg. In the first place the

project was named "Brabazon I" as it was the first and largest of a

number of airliners which were recommended by the Brabazon Committee

presided over by Lord Brabazon, which was set up in 1943 to examine the

needs of British Civil Aviation when the war of 1939-45 ended. Three or

four years ago, the Bristol Aeroplane Co. Ltd., who were building the

"Brabazon I" decided to give it the type name of "Brabazon"

in honour of a greatly respected and loved British pioneer aviator. Brab

is indeed the prototype British test

pilot.

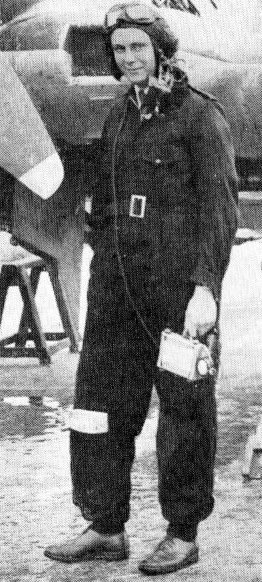

R. P. BEAMONT

D.S.O. & BAR, D.F.C.

& BAR, D.F.C. (U.S.A.), A.R.Ae.S.

ENGLISH

ELECTRIC CO. LTD.

WING

COMMANDER ROLAND PROSPER BEAMONT, D.S.O. (and bar), D.F.C.

(and

bar), D.F.C. (U.S.A.), A.R.Ae.S., became Chief Test Pilot to

the

English Electric Co. Ltd. in May, 1947. In May, 1948, when on a visit

to the United States to fly an experimental aircraft, he flew the North

American P 86 Research fighter at a Mach Number of 1.005 and thereby

became the first British pilot to exceed the speed of sound.

I

am not quoting Beamont when I say it was only that well-known

"caginess" and silly secrecy complex from which our Ministry of Supply

so severely suffers, which prevented the British public hearing at the

time of this feat by a young British pilot. For this was three months

earlier than when John Derry, in the DH 108, was the first to exceed

the speed of sound in the United Kingdom.

Beamont, who is known to his friends as "Bee", was born at Chichester

in Sussex on 10th August, 1920.

He

became interested in aviation at a very early age, because of the

nearness of the R.A.F. station at Tangmere to his home. "I spent a

large proportion of my early life rubber-necking on the boundary of

Tangmere, worshipping my heroes who flew Armstrong Whitworth Siskins,

and later, Hawker Furies," he told me.

After going to school at

Eastbourne College, he made strenuous efforts to get into the R.A.F.,

and as soon as he reached the age of 18 he began to train for a Short

Service Commission in the latter part of 1938. Early in 1939 he learned

to fly at the Reserve School, operated by de Havillands at White

Waltham, on Tiger Moths. When war came in September, 1939, he was at

No. 13 Flying Training School at Drem and continued his flying on

Hawker Hart biplanes, after which he was posted, "fully trained" and

wearing his Wings, to No. 11 Group Fighter Pool at St. Athan where he

graduated on Hawker Hurricanes. It is noteworthy that from the days of

Drem, and right through his operational period, he flew

mainly on

the designs of Sidney Camm, the famous Hawker designer.

Bee

entered the Battle of Britain at the age of 20, and is very typical of

the keen-type Fighter Boys, who went full of enthusiasm and seemingly

tireless into that great battle above the English countryside. How very

young they all seemed, and how "flat out" they were. Even

before

the Battle of Britain began Bee had seen service with No. 87 Squadron

in Hurricanes in France and Belgium during the Battle of France. When

that battle was lost, he returned to England and was first stationed

with his squadron near Exeter.

His first combat with the enemy

occurred during the retreat on Dunkirk when, to use his own words, "I

was a highly experienced (and highly ignorant) Hurricane pilot with 180

hours total flying experience". He went on to tell me how he found

himself cut off from his formation somewhere south of Brussels,

apparently entirely surrounded by Me. 110s.

"The latter all

behaved in a most hostile manner," he said, "and as I had never been in

close combat before, I was too petrified to do anything more than

attempt to disappear in the usual manner in ever decreasing circles!

But eventually one Me. 110 blocked my view for an appreciable period

and got both his motors stopped for his foolishness. However, the air

in my immediate vicinity continued to be so full of tracer that I did

the only possible thing and aileron-turned straight down to ground

level.

"Reaching this strategic position in one piece, I

straightened out in the rough direction of home, apparently over the

top of a whole series of flak posts. Then, to add insult to injury,

horizontal tracer quite close to the cockpit indicated that I was not

only being shot at from the ground, but on looking round I found a

large and corpulent Dornier, sitting some 200 yards behind, insolently

potting away at me with his front gun.

"This pilot, by the way,

was as capable as I was incapable, and when turning round under his

tail I found I had run out of ammunition, and thereupon attempted to

break off the engagement, he did not return the compliment and it took

me some highly energetic minutes to get away from him. None of

this was very glorious, and it was all rather frightening.”

I am

sure that all readers will agree with 20-year-old Bee that this was a

frightening experience for a mere boy in his first battle for life, but

even if he thinks it was not very glorious, it showed he had that

discretion which is the better part of valour. If he had carried on the

fight against unequal odds, no doubt he would have died gallantly

for his country. As it was he lived for his country to destroy

eight enemy aircraft in the air, and many on the ground; to destroy 35

locomotives and trains; and 32 V.1. flying bombs or doodlebugs; and

become one of Britain's leading test pilots.

In August, 1940, he was mentioned in despatches for his work over the

Dunkirk area.

He

served with No. 79 Squadron as flight commander flying Hurricanes from

1941 to 1942 on the night defence of London, escorting bombers over

occupied territory, and offensive sweeps, during which tour of duty he

was awarded his first D.F.C.

In 1942 he took command of No. 609

Squadron equipped with the new Typhoons, during which command he

introduced to Typhoons the new art of train-busting by day and by

night. This art consisted of dislocating the German supply by shooting

up trains with cannon fire, causing chaos and crippling

shortage

of rolling-stock. In three months his squadron destroyed 100 trains, of

which Bee’s personal score was 25.

In 1944 he formed the first

Wing equipped with the new Tempests at Dungeness, and later operated

from Brussels and Volkel. He and his Wing operated over the Normandy

beach heads from D Day, 6th June. Bee himself shot down the first enemy

to fall to a Tempest two days after D Day. That was a Me. 109.

He

and his Wing went into action from 16th June, 1944, against the

doodlebugs during which the Wing destroyed 640 of which he scored 32.

He

led his Wing to Holland in September, 1944, and went into action over

the forward areas and Germany itself. An unlucky incident when low

straffing over Germany put an end, for a time, to his useful career. On

13th October, 1944, he was captured and spent the remaining few months

of the war as a prisoner.

During his very hectic war career, the

hazards of combat were not, by themselves, sufficient fun for young

Bee. So all "rest" periods from operations were spent in learning the

art of test flying. Being highly experienced with Hawker aircraft in

combat, he got himself posted to the firm for a spell. From December,

1941, to July, 1942, he tested production Hurricanes and Typhoons. Then

he had a further 14 months as No. 2 experimental test pilot to George

Bulman. Before he returned to operations in March, 1944, he shared the

development test flying of the Tempest with Bill Humble.

In

January, 1943, he was awarded a bar to his D.F.C. for his

train-busting, and in May the same year he won his first D.S.O. In

July, 1944, he was given a bar to his D.S.O. for dealing with

doodlebugs, and in March, 1946, came his United States D.F.C.

On

repatriation at the end of the war, he was posted to command the Air

Fighting Development Squadron at the Central Fighter Establishment.

He

then spent a time as experimental test pilot with Gloster Aircraft, and

with Eric Greenwood did much of the development flying with the Meteor

4, preparatory to the successful attack on the world speed record in

1945. He reached a true speed of 632 m.p.h. on test. He then had a

period with the de Havilland Aircraft Co. as military demonstration

pilot. I well remember the wonderful show he made at the first post-war

Society of British Aircraft Constructors' Air Show at Radlett

in

September, 1946, with a Vampire.

His flying of the Vampire first

brought him into contact with the English Electric Co., as this firm

built all the first production Vampires when de Havillands were too

busy with Mosquito production to build this later design of theirs.

The

English Electric Co. had previously "dabbled" with their own designs,

having built an ultra-light plane, the Wren, in 1923 and one or two not

very successful flying-boats.

Their experience with the Vampire

and Halifax provided a good background for setting up their own design

department, and in 1949 they produced the Canberra, the first British

jet bomber to the design of W. E. Petter who had previously designed

the Westland Whirlwind, Welkin, and Lysander. Bee made all

the

prototype tests and caused something of a sensation by his handling of

it at the 1949 Air Show at Farnborough. The hard-bitten spectators

gasped with surprise as he threw it about as though it were a small

fighter. There was an emotioning moment too, on that first day, when

after a roll, bits were seen to fall from the aircraft. But the "bits"

were loose rags and bits of cloth, which fell from the

bomb-bay

whose doors he had opened to slow up.

In all he has flown close

on 2,800 hours on 98 different types, including 10 different jet types.

He has made over 1,700 test flights. His operational hours against the

enemy totalled 650, all of which is a surprisingly high total for one

who looks so

young.

T. W. BROOKE-SMITH

A.R.Ae.S.

SHORT

BROS. AND HARLAND LTD.

SINCE

March, 1948, Thomas William Brooke-Smith, A.R.Ae.S., has been Chief

Test Pilot to Short Bros. & Harland Ltd., succeeding John

Lankester

Parker who filled that post for the record time of 29 years, and

Geoffrey Tyson.

Tom Brooke-Smith was born in Lincolnshire on

14th August, 1913, when Parker had already begun testing for Short

Bros. He was quite a small boy when his attention was first turned to

aviation problems.

"Rudimentary steps were with a cat. Little

beast that I was, I could not resist projecting it through my nursery

window and seeing it land the right way up, regardless of the attitude

when launched," he told me. "Those experiments were carried a

stage further a year or so later. On sunny afternoons, and when the

gardener wasn't about, I tried my hand at parachuting off a 10 ft. wall

on to an asparagus bed with the aid of my father's best umbrella!"

Both

those incidents show that "Brookie" began his early enquiries into the

aerodynamical future in an exceedingly practical manner, both as

regards undercarts and life-saving devices.

His first real

contact with an aeroplane came in about 1926 when he was about eight

years old. An Avro 504k was giving joyrides from a small field near his

home, and he remembers how much he was impressed by the pilot with his

leather flying-coat, helmet, and goggles.

"I was also most

impressed," he said, "with the strong smell of castor oil, and from

then on this smell had only one meaning for me—aeroplanes.

This, of course, was the start of it all, and some few years later, at

school, when I was about twelve years old, I was asked if I had given

any thought to a future career. 'Yes,' I said, 'aviation'."

He

was educated at Bedford, a school which produced many names now famous

in aviation such as Claude Grahame-White and R. J. (Spitfire) Mitchell.

Cardington, near Bedford, was then the home of the airships R 100 and R

101 which the Bedfordians referred to as "ours". Brookie watched the

take off of the 101 on its disastrous start for India when it crashed

in France killing most of its crew. He recalls that the ship behaved

with sullen obstinacy when ascending from the mast, and many who saw

her, shook their heads to one another. "I never went much on

airships after that," he said!

After leaving Bedford College he

entered the College of Aeronautical Engineering in 1934. Many of his

friends have heard a story that he ran away from school to learn to

fly, after watching aeroplanes at the R.A.F. base at Henlow, but that

is quite untrue.

After completing his course at the College of

Aeronautical Engineering, he joined the Brooklands School of flying

under Duncan Davis. "The day I passed through 'Shell-Way', the road

into the famous Brooklands Track, en

route for my first lesson, will stay in my memory

so long as I live," he told me recently.

He

flew solo for the first time on the day following his seventeenth

birthday, his age having disqualified him for doing so any earlier.

That is, of course, the greatest milestone in any aviator's career, and

of course Brookie was thoroughly thrilled by it. It was not many days

before he made the necessary flying tests for his Royal Aero

Club Aviators' Certificate and his Pilot’s "A" Licence.

"It

was here at Brooklands," he told me, "watching people like Mutt Summers

and Jeffery Quill of Vickers, Hindmarsh and Dick Renell of Hawkers, in

action, that I made up my mind then and there, that I would, at all

costs, ultimately become a test pilot myself."

A few weeks

after gaining his "A" Licence he became a private owner, a very proud

private owner, of a red and silver Puss Moth. With that aeroplane he

had what he describes as "a good many escapades, more than a few near

misses, and a lot of fun".

When flying about England he

preferred to use fields rather than aerodromes, and a lift in the

baker's cart as far as the village from a neighbouring meadow was a

frequent occurrence on his week-end visits to his father in

Lincolnshire.

During the next two years, which separated him

from the qualifying age for a Pilot's "B " Licence, he thought he would

like to get some practical experience of everyday running and

maintenance of aeroplanes.

He joined Continental Airways Ltd., a

well-known air line firm at Croydon. He was taken on as a labourer, and

worked six days out of seven, with a night shift every other week. His

pay packet contained twenty-five shillings weekly, and he set out to

live on

that.

After deducting Health Insurance Contribution, that left nothing except

just enough for board and lodging.

At

first he had little to do but clean cowlings in a paraffin bath. The

only times he came into contact with aeroplanes would be after a bumpy

trip when malaise de

l'air

had wrought its usual distressing results in the cabin, which Brookie

had to clear up. But he says that in spite of all that "naturally I

enjoyed it"!

Soon after his nineteenth birthday he got his "B"

Licence and he took a job with a small joy-riding and charter firm.

Almost his first job was to take a middle-aged couple to France. He was

completely green as regards Customs formalities, but put on an

outward show of confidence.

"The flight went off well," he

said, "and on taking leave of my customers a piece of paper was pressed

into my hand. It was a five pound note, and more than my week's wages;

and it was the first time I had ever been tipped in my life."

He

had another regular customer, always beautifully dressed, whom he flew

to Le Touquet about twice a week to play roulette. This passenger

practiced with his own wheel in the air. Brookie thought he was

probably a wealthy stockbroker, but ultimately discovered that he was a

curate!

When war came on 3rd September, 1939, he was with the

Hon. Mrs. Victor Bruce's Air Dispatch Ltd. and operated much in France

in the very hard winter of that year. He told me that the Air

Registration Board would have shown severe displeasure if they had

known of his use of a paraffin stove in the cabin to keep from freezing!

Then

came the opportunity to fly many varied types of aircraft during a

period with Air Transport Auxiliary, which ferried Service aircraft

from factories to squadrons.

In 1942 he joined Short Bros. as a

junior test pilot. Lankester Parker was then Chief Test Pilot. He

started with Stirling bombers and Sunderland flying-boats from the

production line. He can justly claim more than a modest share in flight

testing many of those famous aircraft as well as Sandringhams, Hythes,

Plymouths, Bermudas and Solents.

At the beginning of 1947, he

"went back to school", for a course at the Empire Test Pilots' School

from which he graduated the same year, and when Geoffrey Tyson left the

firm, Brookie was appointed Chief Test Pilot. Since then his has been

the main responsibility for testing the Sealand Amphibian, Sturgeon 2,

and the latest type of Mark 4 Solents delivered to Tasman

Airways.

He

has logged 4,500 hours flying on 120 different types which include

fighters, bombers, airliners, seaplanes, sailplanes, amphibians, jets—and of course flying-boats.

Brookie

told me that his narrowest escape from the obituary column was in a

motorcar! He went to sleep at the wheel and ended half way up a railway

embankment!

He had two "near-misses" in the air. First he was

flying an aircraft which was over-flapped and under-elevatored. His

first landing was baulked. When he opened up for another circuit, the

aircraft took a determined header for the water. "Handfuls

of elevator made not the slightest difference; the flaps

operated

just quick enough to save my life," he says.

When flying a

Hurricane, a nut, left behind by a careless fitter, stripped the glycol

pump. Hot steaming atomised glycol came up into the cockpit and covered

him from head to foot. Having no oxygen, he was forced to open the

canopy to breathe and to see. That made matters worse by

creating

a 'forced draught'. The motor got the glycol internally and began

coughing it out through the exhaust stubs on both sides.

This is

Brookie's own account of what then happened: "Becoming blind,

I

realised I had to get out of the sky smartly, or else jump for it. I

made for an expanse of grass, of which I managed to get occasional

glimpses, and somehow arrived in one bit—hurriedly

leaving the aircraft where it had rolled to a standstill. The place was

an Elementary Flying Training School grass aerodrome, and it was

swarming with Tiger Moths doing circuits and bumps. I leant on the tail

plane and wondered how the hell I happened to roar in among such a

swarming melée of Tigers without hitting

one!"

G. R. BRYCE

VICKERS-ARMSTRONGS LTD.

A

SCOTSMAN born and bred, it is hardly surprising that Gabe Robb Bryce is

known to all his friends as Jock; for his two Christian names are not

those which would come easily or familiarly to a Sassenach!

Since

the beginning of 1946 jock has been "right hand man" and assistant

chief test pilot to Mutt Summers at Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd., at Wisley,

Surrey.

Under the guidance of Mutt Summers, Jock was introduced

to the arts and crafts of test-flying in the first Viking; he is the

first to agree that he could not have learnt the gentle art from a

better man than Mutt who has been test-flying Vickers aircraft since

1929.

Jock attributes his interest in aviation to a proximity to

Prestwick in his youth. He was born in Scotland on 27th April, 1921,

within easy range of Prestwick. Aviation was brought right into the

Bryce family circle when his elder brother was on the first R.A.F.V.R.

course at Prestwick in 1936. Quite naturally the fifteen year old

Jock was thrilled with the thought of being a pilot himself

one

day, to emulate his brother, who was killed in April, 1941, flying a

Bristol Blenheim 1 in action in Greece against a Me. 109.

Jock’s

first close introduction to flying was as a greatly admiring spectator

of the pupils of the R.A.F.V.R. flying de Havilland Moths and Hawker

Harts.

As soon as he was old enough Jock joined the regular

R.A.F. early in 1939, and was lucky enough to be stationed at

Prestwick. He was fortunate enough to become aircrew at once, but was

not satisfied because he was trained as a navigator and not a pilot. At

that time the great importance of navigators had not been realised,

especially by the young and impatient, all of whom wanted to be

"drivers".

He continued with his navigator's course after war

came in September, 1939, now more impatient than ever, and completed

the course at No. 10 Bombing and Gunnery School at Warmwell. He was

posted to a newly-formed Operational Training Unit in South Wales

equipped with Boulton Paul Defiant 2-seat fighters, and eventually

established for himself a position in a Special Duties Flight attached

to Fighter Command.

Early in 1942 he transferred to Coastal

Command and served as a navigator in Wellingtons, where one of his

contemporaries as an air gunner was John Derry.

About the middle

of 1942 the Air Officer Commanding Training Command was becoming

somewhat worried about the personnel material available for

pilot-training and so he selected 500 tour-of-duty-expired navigators,

wireless operators, and air gunners to take a Pilot Course. Jock was

one of the lucky ones to be selected, as also was John Derry.

It

had become a very sore point with tour-expired semi-unemployed aircrew,

who found it was impossible to remuster as pilots, to see many bank

clerks, salesmen, insurance canvassers, journalists, which impatient

air types always seem to regard as less suited than themselves for it,

going to Canada or South Africa for the much sought-after pilots'

course.

Jock was posted to Canada and completed his training as

a pilot in 1943, in a somewhat dubious state of mind. He had by now a

considerable sum of experience as a navigator, but a total of only 61

hours in the "1st Pilot" column. That was the condition in which Jock

found himself when he reported for duty, wearing his coveted Wings, at

No. 45 Atlantic Transport Group at Dorval, Montreal.

He at once

began the job of ferrying aircraft across the Atlantic, from Gander to

Prestwick. Atlantic flying had not really begun to be the routine job

it is to-day, so it might seem rather a frightening first assignment

for a new and very young pilot. Jock took it in his stride, and by 1945

he had become a seasoned old hand, having completed 32 crossings on

Dakotas, Mitchells, Bostons, Liberators, and Lancasters.

He

made

his first trip as Captain in full charge after his flying time had

increased to only 157 hours; he flew a Dakota from Montreal to French

Morocco. There was one rather "dicey" occasion when he was taking a

Boston from Gander in Newfoundland to North Africa. "I landed at the

Azores with such a minute quantity of fuel left that the very thought

still makes me wonder!" he told me. "Then there was that return Ferry

Service on B.O.A.C. Liberators from Prestwick to Montreal

direct

in 17 hours. There were no seats, no heating, one sleeping bag

between us, one box of rations, and a chromium plated piece of

ironmongery on the passengers bulkhead neatly labelled 'Iced Water'. We

had to use oxygen for 11

hours of the 17." Passengers in the comparatively luxurious airliners

of to-day can just ring a bell for a steward or stewardess and complain

that the cabin is too hot or too cold, or a well-cooked meal is not

quite to their liking, in mid-Atlantic!

There

was one incident, when ferrying a twin-motor aircraft from Prestwick to

the South of England on a very dark night during the war, which might

have ended much more unhappily. The night was more than usually dark

when his port motor quit. He was still struggling along

hoping to

find a landing-ground, and had dropped to 2,000 ft., when the other

motor also stopped. Jock had no option but to land straight ahead as

best he could, which might well have been in the middle of a town, or

he might have hit a hillside or a building at flying speed. He did all

the necessary drill for a blind forced landing, and hoped for the best.

He was lucky, for he landed comparatively safely in a wood.

He

then was posted for a 12-month tour with No. 232 Squadron, the only

Skymaster Squadron in the R.A.F., which opened up a new route for

R.A.F. Transport Command from Ceylon to Sydney. In July, 1945, he flew

the trans-Australian route from Perth to Sydney in 8 hours 50 minutes,

establishing a new Australian record, unofficially. When the war ended

he ferried the last R.A.F. Skymaster from Ceylon to the United States,

which operation was organised by Air Commodore E. H. ("Mouse")

Fielden, the Captain of the King's Flight. That contact resulted in

Mouse appointing Jock as Captain of the 3rd aircraft of the Royal

Flight.

This proved to be a short appointment. The flight was

being equipped with Vickers Vikings, and Jock was thus brought into

contact with Mutt Summers who was building up the post-war team of

Vickers test pilots. Apart from Jock being a type whom most people

would like on first sight, he had acquired a fine record and

reputation. Mutt told me a couple of years ago that Jock was just the

type for whom he had been looking. I do not think he has had any cause

to revise his original estimate. Having learned the art of testing on

the first Vikings, Jock flew with Mutt on the first flights of the

Nene-Viking, Varsity, and Viscount. He has done over 500 hours flying

in the Viscount, making the tests for the new International Civil Air

Organisation standards before the normal Certificate

of Airworthiness was granted.

He has also flown more than

80 hours in the Nene-Viking, which although it is regarded as just a

flying test-bed, was in fact the first jet airliner to fly. The honour

of being the first jet airliner designed as such from the start, goes,

of course, to the de Havilland Comet.

The Nene-Viking has a

magnificent ceiling. On at least one occasion in its very early life it

was intercepted at nearly 40,000 ft. by a flight of Gloster Meteors.

The maximum ceiling of a normal Viking is not more than 15,000 ft., so

the R.A.F. pilots were extremely puzzled at meeting what they at first

took to be a normal Viking up in the stratosphere. Closer inspection

revealed unfamiliar engines in a familiar airframe and solved the

puzzle for them!

Jock is a worthy follower in the slip-stream of

the great men who have tested for Vickers, who include Harold Barnwell,

Gordon Bell, Jack (later Sir John) Alcock, Stan Cockerell, Tommy Broom,

Tiny Scholefield, and Mutt Summers. He has flown 4,500 hours on 54

different types. He was very largely responsible, with Mutt, for the

quick way in which the Viscount, the world's first turboprop airliner,

progressed from the unknown experimental to the reliable operational

type which it soon

became.

F. J. CABLE

A.F.C., A.R.Ae.S.

CHIEF

ROTARY WING TEST PILOT, MINISTRY OF SUPPLY

F.

J. CABLE was one of those comparatively rare birds who only flew with

rotary wings. He considered that fixed wing aircraft which stall, and

therefore land, at a high rate of knots, are highly dangerous waggons.

He had flown in fixed-wing aeroplanes as a passenger, but only when

there was no heli-go-round going his way. He was known to a large

circle of friends as "Jeep", which name was bestowed on him in 1933

when he first flew autogiros, and therefore before the days of the Jeep

car. In the "Pop-eye" cartoons there was a curious animal

called

a Jeep which used to send messages called jeep-o-graphs with its tail,

and Cable was alleged to do the same; whether he did this "by Cable" on

the ground or in the air, I wouldn't know!

He had completed nearly 2,000 hours as a pilot, entirely on rotary wing

aircraft, both autogiros and helicopters.

In

this series of articles I ask each victim to tell me how he first came

to be bitten by the aviation bug. But I have no need to ask Jeep that,

as it was I who first supplied the bug!

'Way back in 1931, there

were no youth organisations to help boys who were keen on flying, and

there was no A.T.C., so I formed a flying club for telegraph boys of a

cable company. To get on easy terms with the boys, I had myself made a

cable messenger, and was fitted out with messenger's uniform. I was a

fairly large size, and the question of fitting me with a uniform was

something of a problem, so the biggest messenger was sent for and was

told to take off his uniform which I donned. That messenger was No. 161

F. J. Cable of Stratford in east London, and the rapid exchange of

clothing formed a bond of friendship between us, which endured.

I

took the boys to aerodromes at week-ends and wangled free flights for

them. I got certain companies to undertake to teach some of them to

fly. Señor Don Juan de la Cierva, inventor of the autogiro, agreed to

take one, so I selected Jeep. After he had learned to fly an autogiro,

he showed such promise that he was taken on the strength of the Cierva

Autogiro Co. Ltd.

He qualified for his Royal Aero Club Aviators'

Certificate on an Autogiro C 19 Mk 4 on 21st September, 1932. A few

days later I was his first passenger when he was not yet seventeen; we

were both in our telegraph-boy uniforms. When he reached the years of

discretion we often wondered at my bravery or foolhardiness. Now I am

getting much older and wiser, but I had complete confidence in the

autogiro and in Jeep's sound common sense, which I now know was not

misplaced.

At that time, he was the first pilot in this or any

other country to qualify for his Aviators' Certificate on rotary wings,

and he was certainly the youngest to fly an autogiro.

He gained

his "A" and "C" Ground Engineers licences in June, 1936, at the

Autogiro Co's works at Hanworth airfield, and his instructors'

endorsement in April, 1939, and did such useful work for the rotary

wing units of the R.A.F. after the outbreak of war that he was

commissioned in the R.A.F. on lst January, 1941.

Right from the

start of his air career, he served under Reggie Brie and Alan Marsh to

both of whom he owed much of his success. He was regarded as No. 3

Helicopter pilot of Great Britain, and should rightly have been awarded

R.Ae.C. Helicopter Certificate No. 3 if these had been issued in

chronological order instead of in order of application.

He was

the second Britisher to fly the Sikorsky helicopter, in 1943; and on

22nd January, 1944, he was the first in the United Kingdom to fly a

Hoverfly, from ship to shore, which he did off M.V. Daghestan

off Liverpool. Within a week he flew the machine from Speke to

Hanworth, the first helicopter cross-country flight in this country.

After

that he instructed the first batch of test pilots and instructors in

Britain on helicopters. In the early days of the war he did valuable

Radar work with autogiros for No. 60 Group. He reached the rank of

Squadron Leader by the end of the war, and was awarded the A.F.C.

He

considered that his narrowest escape was in 1945 when he was giving

instruction on a Hoverfly to Squadron Leader "Pat"

Hastings, A.F.C., A.F.M., a test pilot from Boscombe Down. Jeep

told me, "Pat was

flying the aircraft and the first I knew that something

was wrong

was when the stick started to hit my leg and we were still flying

level. I took over and made to get back to the 'drome. We were about

1,000 ft. at the time, and over the houses which border the 'drome. At

about 700 ft. the control fell apart with quite a bit of vibration to

the aircraft, and we spun down almost vertically, and hit the barbed

wire just on the edge of the 'drome. That undoubtedly cushioned the

impact. The stick went through the seat I had been sitting on, but

fortunately I had leapt out of it just before we hit, and was holding

on to Pat's neck. Although the aircraft was finished, we were only

slightly scratched."

As he knew that all Hoverflys would be

grounded pending enquiry into the cause of the accident, he at once

flew another machine before the ban could be imposed, so as to restore

his rather shaken nerves.

Towards the end of the war he was

appointed Officer Commanding the first Ministry of Aircraft Production

Rotary Wing unit, formed at Hanworth, and later he moved with the Unit,

now of the Ministry of Supply, to Beaulieu. When he was demobilised, he

was appointed Chief Rotary Wing Test Pilot to the Ministry of Supply at

Beaulieu, which post he held until his death. Soon after that posting,

I had my second flight with him, in a Sikorsky S 51, which he was

demonstrating at Harrods' Sports Ground near Hammersmith. I was

particularly impressed by the difference between the raw 16-year-old

sprog of 1932 and the experienced star helicopter pilot of

1947.

He had less than 100 hours to do before completing his 2,000 hours. If

he had completed that time, he would have been the first in the world

among those who had only flown on rotary wings to log that coveted

2,000 hours.

Jeep was married with a family. Aviation, and

particularly rotary wings, had got so deeply into his system that he

never recovered from it. He should be an example to all boys and young

men in all walks of life, as a man who, perhaps by luck, had a

wonderful opportunity put in his way, which he seized with both hands

and never let go. The road to failure is paved with lost opportunities.

Moreover, Jeep, unlike so many others, never forgot what he thought he

owed to those who helped him. I am proud to be one of those whom he did

not forget. If he had not been made of the right stuff he could

not have achieved his success.

I am sure he would have made

good in any walk of life which he had chosen; and I am also sure he

would not have got as much fun out of life as he did from

heli-go-rounds. I was very proud to think that I was primarily

responsible for launching a boy, such as he then was, on a career which

brought him such success.

On 13th June, 1950, Jeep was flying,

as second pilot, with Alan Marsh in the Cierva Air Horse near

Southampton, when the machine crashed, due to some structural failure

at about 400 ft., and both Jeep and Alan, with a flight engineer, were

killed.

Having been primarily responsible for getting Jeep into

aviation I feel I am in part responsible for his death, but I know that

the past 20 years had brought him so very much happiness and interest,

and so many staunch friends that I cannot feel blameworthy. In the loss

of Jeep and Alan the world has suffered a very great loss for their

combined knowledge and experience of helicopter flying is incalculable.

When I think back less than 20 years, when I first met Jeep in his

telegraph boy's uniform, it is indeed a romance, though a very sad one,

that I can truthfully write of his death as so great a loss to the

world. It will be long before I meet another friend so true. He will

not be

forgotten.

LESLIE R. COLQUHOUN

G.M., D.F.C., D.F.M.

SUPERMARINE DIVISION,

VICKERS-ARMSTRONGS LTD.

LESLIE

ROBERT COLQUHOUN, G.M., D.F.C., D.F.M., is assistant test pilot, under

Mike Lithgow, to the Supermarine Division of Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd. He

has his headquarters at Chilbolton aerodrome in Hampshire near which he

lives with his wife and three daughters. Though Les looks a bit young

to be the father of such a family he is, at the time of writing in

August, 1950, just over 29 years old.

He was born at Hanwell,

London, on 15th March (the Ides of March), 1921; but no one issued any

stern warning to any dictators, though well they might!

He was

educated at Drayton Manor Grammar School. He does not remember any

special reason for taking up flying. When war broke out in 1939, he

thought, as others have thought before him, that if he had to go into

battle it would be much more comfortable to do so sitting down in a

nice warm aeroplane than plodding on his flat feet !

Soon after

he was nineteen he applied to join the R.A.F. as a pilot, and in due

course was called before a selection committee. "I did not put

up

a very good show," he told me, "as I could not do their sums. I was no

good at maths and told them so. At first they put me down as an air

gunner. They then asked me a few commonsense questions which I

answered, so they crossed out 'gunner' and put down 'wireless op';

after that they asked me a few questions about French Somaliland which

I was able to answer as I had just read about it in the

papers.

The result was that they crossed out 'wireless op' and put me down as a

pilot."

Like most sensible types, Les does not like having

anything shot at him, be they shells, bullets, or questions. Questions

particularly scare him stiff, and he recalls that selection board as

one of the most frightening events of his career!

He is one of

those people who is not scared easily in the air, but who is put into a

state of nervous prostration when taking a test or sitting for an

examination. He is an outstanding example of how wrong are the present

Air Ministry authorities in placing such importance in exams, when

selecting aircrew. If Les had to pass through the nonsense of present

day A.T.C. Proficiency tests and what is thought to be necessary to get

into the R.A.F. as aircrew, now that 'know-how' and keenness are not

considered sufficient, he would very likely be among those turned down.

Soon

after he joined the R.A.F. as an L.A.C. he passed through No. 18

Elementary Flying Training School at Fairoaks on Tiger Moths. This was

the time of the Battle of Britain and naturally, like all boys, he

wanted to become a fighter pilot. After qualifying for his

Wings

he was posted to No. 603 City of Edinburgh Squadron as a Sergeant-pilot

in October, 1941. This squadron was then stationed at Hornchurch, and

equipped with Spitfires. In November, 1941, Les went north with the

squadron to Dyce, which became the civil airport of Aberdeen. In

February, 1942, he went south to Benson near Oxford, which was the home

of Photographic Reconnaissance Units (P.R.U.) equipped with Spitfires.

In April, 1942, he was one of a party detailed to fly some P.R.U.

Spitfires to Cairo. They flew via Gibraltar and Malta.

They

reached Malta just at the time when the Island was in a state of seige

and was receiving the bombing attentions from the Luftwaffe several

times daily. Les recalls making a wide circuit of the beleaguered

island before landing, and thinking how lucky he was that he would soon

be on his way again to safer places. When he landed at Luqa aerodrome

he was told that he and his Spit would be remaining at Malta as a

P.R.U. machine was badly needed. He thought this was shattering news at

the time and quite a lot of sleep was lost that night which could not

altogether be attributed to the unwelcome attentions of the Jerry

bombers. However, no suitable excuse could be found to wriggle out of

the situation so he stayed. Though he was there in the hottest days of

the battle, he now considers himself to have been lucky to have been

there in Malta's greatest days.

He flew a Spitfire 4, with no

guns. It was used solely for reconnaissance and photography and relied

on its speed for protection. Les does not admit to having any really

dangerous moments or narrow squeaks, but he admits to two incidents

which "upset me most". The first of these was on a flight over Sicily.

His squadron had just received a consignment of chocolate, which was

considered almost as valuable as gold. Les took a packet with him to

eat during flight.

"I

was flying over Cape Passero, the south

eastern extremity of Sicily, and came down to 16,000 ft. to take off my

oxygen mask to eat some chocolate before setting course for Malta.

Suddenly I saw a shadow and just behind me, almost in formation, was an

Me. 109. His guns must have jammed, or he was out of ammunition, or was

a pupil on a training flight, for he did not fire at me, and of course

I had no guns. I called up Luqa madly for help, but the 109 flew away

and all ended well for me!"

That

incident must have been extremely upsetting, for it seems fairly

certain that the Me. 109 guns had jammed; a Hun on a training flight

would not have been nosing around a Spit, nor would he have done so if

his ammunition was running low. He obviously had evil intent!

In

June, 1942, Les had the job of flying around Italian ports, including

Naples, Taranto, Messina, Augusta, and Palermo, to find out the

disposition of the Italian fleet. Late on the evening of 14th June that

year, when the light had faded too much to take photographs, he saw a

force of two cruisers and four destroyers steaming out from Palermo.

About this time a British convoy was coming through the Med en route

for Malta. The information Les brought back enabled the necessary

action to be taken and one cruiser was subsequently damaged by a

British submarine. For this valuable reconnaissance, after months of

difficult and dangerous unarmed P.R.U. work, he received the D.F.M.

Shortly after this, he was commissioned.

During his eight months

in Malta he did an enormous amount of flying over enemy territory and

sea; he logged over 500 hours in that time so thoroughly earned his

promotion and decoration. He was in Malta most of the time of its worst

peril from possible assault and during the worst of the bombing. He

went back to the United Kingdom in December, 1942.

At the

beginning of February, 1943 he was posted to the P.R.U. at Dyce again,

but this time as an instructor, and he remained on that job until

October, 1943. Then he was posted to No. 642 P.R.U. Squadron at Tunis,

and in December of that year moved with his squadron to Italy

and

served with them at San Severo until October, 1944, when he returned

once more to Dyce to serve as an instructor with No. 8 Operational

Training Squadron. He moved with them to Haverford West and in

February, 1945, when Jeffery Quill, Chief Test Pilot of the Supermarine

Division of Vickers, wanted another test pilot, Les was sent to join

him at High Post in Wiltshire as his qualifications and temperament

were just what Quill wanted.

The signal that he had been

selected and was to be posted to Supermarines was one of the big

moments of his life and has shaped his destiny—so far as it has gone.

He proved to be a good man on production test work, and he continued on

this work as a flight lieutenant until April 1946, when he was

demobilised.

"The only difference that made to me," said Les,

"was I arrived one day for normal work in uniform, and the next day in

civvies as a complete civilian on the test pilot staff of Supermarines."

Apart

from his work in testing production machines, he had an interesting

diversion when he went as second pilot on the delivery flight to Buenos

Aires of the President's personal Viking. The route was via Iceland,

Greenland, U.S.A., Nassau, Jamaica, Natal, and Rio.

Since the

retirement of Jeffery Quill as Chief Test Pilot, Les has been second to

Mike Lithgow who succeeded Quill. In that capacity he has flown the

Swift, Attacker, and Seagull in their early prototype stages.

Rather

more "upsetting" than the incident of the chocolates and the Me. 109

was an occurrence on 23rd May, 1950, for which he was awarded the

George Medal. He was flying the first production Attacker making some

experiments with the dive brakes. When he was making a fast run near

Chilbolton aerodrome at 450 knots (about 520 m.p.h.) he heard a loud

bang, and to his amazement he saw that the starboard wing tip, a

section 3 feet 6 inches in span, had folded up and was standing

vertical. His first thought was to use the ejection seat, and his hand

moved to grasp the handle which jettisoned the cockpit cover to bale

out, but after the initial temporary loss of control the aircraft still

seemed the right way up so he decided to attempt to land it. Aileron

control had gone because when the wings of an Attacker are

folded,

the ailerons are automatically locked in neutral. He found that by

coarse use of the rudder it was possible both to keep the aircraft

level and control it directionally in a limited way. He made a wide

circuit and began the final run in at 230 knots.

"It was then

that I realised the real difficulties, and that a very fast touch down

speed would be necessary," he told me, "as at speeds below 230 knots

(265 m.p.h.) the aircraft could not be kept lined up with the runway,

nor could it be kept laterally level. I crossed the aerodrome

boundary at this speed and touched down on the end of the runway at 200

knots (230 m.p.h.). By juggling with the elevator and brakes to keep

the aircraft on the ground, I finally pulled up ten yards short of the

end of the 1,800 yard runway, the only further damage being a

burst port tyre which was due to the heat generated by the excessive

braking required to stop the aircraft; for 200 knots is almost twice

the normal touch down speed of the Attacker."

He landed the

Attacker mainly intact so that the machine was examined for the cause

of the failure and the defect was put right so that it could never

happen again for the same reason.

By his pluck in remaining with

his aircraft Les saved the country many thousands of pounds and no

doubt prevented months of delay to Attacker production, pending further

experiments.

The whole aircraft world was delighted to hear that

the King had awarded him the George Medal for his pluck. A test pilot's

work is always full of unknown hazards, and it has been said that is

what they are paid for. As I have said in other cases, that may be so;

but all test pilots are paid thoroughly inadequately, in my opinion,

for the valuable work they do. Here is an example of how much money a

good conscientious pilot can save his firm. That is my opinion

entirely, and the thought has not been put into my mind by Les or any

other test pilot.

The incident happened on the Tuesday of

Whitsun week. The next day Les flew a Wellington and then the firm

closed down for Whitsun. That break from flying gave him time to think

and he had a slight reaction of nerves three days later, which was not

helped by having to endure the natural suspense of becoming a father.

He has flown just over 3,000 hours on about 25 different types of

aircraft.

R. M. CROSLEY

D.S.C.

SHORT BROS. AND HARLAND LTD.

LIEUT.-COMMANDER

ROBERT MICHAEL CROSLEY, D.S.C. and Bar, has been assistant test pilot

to Short Bros. & Harland Ltd. at Belfast since 1948. He was

born at

Liverpool on 24th February, 1920. "That was only because my mother

happened to be there at the time, for we were a Hampshire family," he

said. He went to school at Winchester, first at the Pilgrims' School

and then at the famous public school founded by Edward VI. On

leaving school Mike entered for the Navy but failed in 1937

so he

joined the Metropolitan Police with the idea of a course at Hendon

Police College in mind. He had just finished his training when war

broke out in September, 1939.

During the early months of the war

the weather was very hot and Mike found that a policeman's uniform was

unpleasantly so. Therefore he made early application to join the

R.A.F., and the Fleet Air Arm, as he felt he would be of more use as a

pilot than as a policeman. Making a simultaneous application to the

R.A.F. and the Navy caused quite a bit of muddle at the time, and did

not get him any quicker out of the Police Force. He passed medical

examinations and interviews for the R.A.F. and F.A.A. all over the

place, and was eventually "poured into bell-bottoms" and began training

as a cadet at Gosport in October, 1940.

"After so much blitzing

as a 'copper' in the West End of London," he told me, "it was a welcome

relief to be out of the police and into bell-bottoms. Thank goodness

there was a shortage of pilots and not observers, but I was even keen

to be an observer! My father had been against my joining the R.A.F. in

peace-time, as it was a short service commission and had no future. In

any case he asked me how I knew I could be good at flying, for he said

it would get me nowhere being just mediocre. I was, of course,

absolutely certain I would be a first-class pilot. After all I had

never been either airsick or seasick, and could drive a car really

dangerously at times!"

After

Gosport he was posted to Luton where Shorts were operating the

Elementary Flying Training School. He was initially trained on

Magisters which were monoplanes, and liked to think this gave him a

better chance of becoming a fighter boy than if he had gone to the

other Naval Elementary Flying Training School at Elmdon which flew

Tiger Moths. The pupils on Mike's course were quartered in some very

draughty stables at Luton Hoo and everyone else caught 'flu or

pneumonia, so he managed to progress quickly and went on an earlier

course than his contemporaries, to Netheravon, flying on Hawker Harts

and Fairey Battles.

"By this time we were, of course, real old

hands," Mike told me, "having nearly 50 hours flying to our credit!

There was one incident which I recall, during the time I was building

up this 'colossal' total of hours. I had a friend who had contrived to

fly solo at the same time as myself one fine sunny morning. We played

around in and out of some lovely cumulus clouds and got lost. He made a

perfect landing in a field near St. Albans and asked someone where he

was, and flew back to Luton, and no one else was any

the wiser. I,

like an ass, nearly ran out of petrol before I really admitted to

myself that I was lost. I selected a field for a forced landing,

overshot completely, and landed in the next one, just missing a horse

which did not even see the aircraft and completely ignored me. The only

damage was that the railings on the far side of the field dug into the

main plane leading edge. It was useful experience though."

After

passing through his Secondary Flying Training School at Netheravon,

Mike was allowed to shed his bell-bottoms and climb into

sub-lieutenant's uniform for the first time. "I can never remember a

happier moment than when I donned that new uniform for the first time,

got into my very ramshackle M.G. car (of course it had to be an M.G.)

and drove to Yeovil town to begin a course with an Operational Training

Unit on Hawker Hurricanes."

After a delightful period of training there in the summer of 1941 he

was appointed to the carrier, H.M.S. Eagle, which he

joined on a very rainy night at Liverpool—his birthplace. No one could

quite understand why he had come, for the Eagle