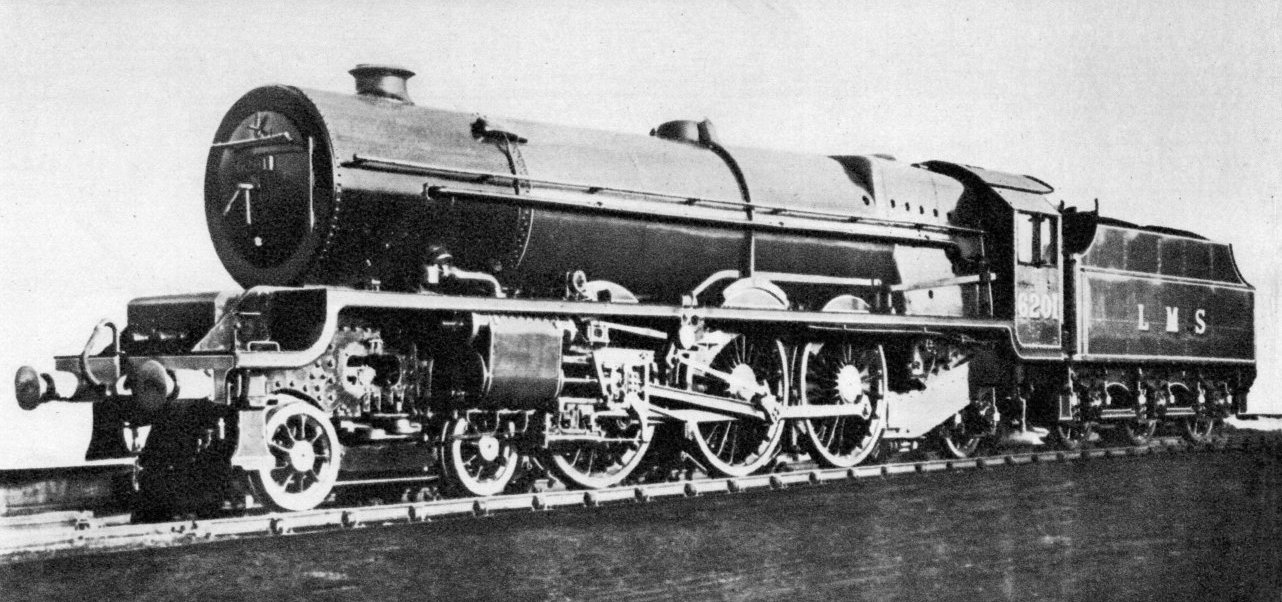

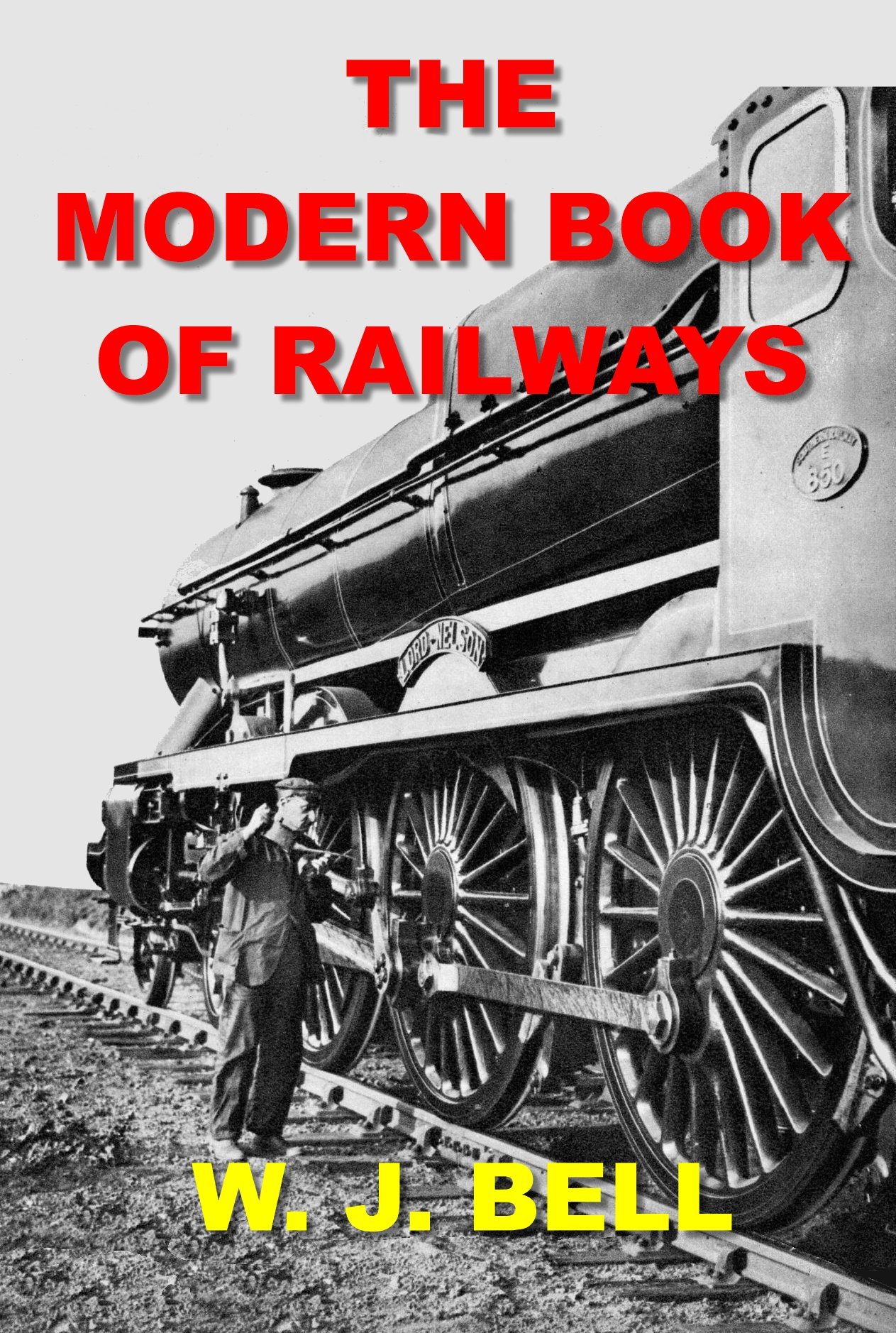

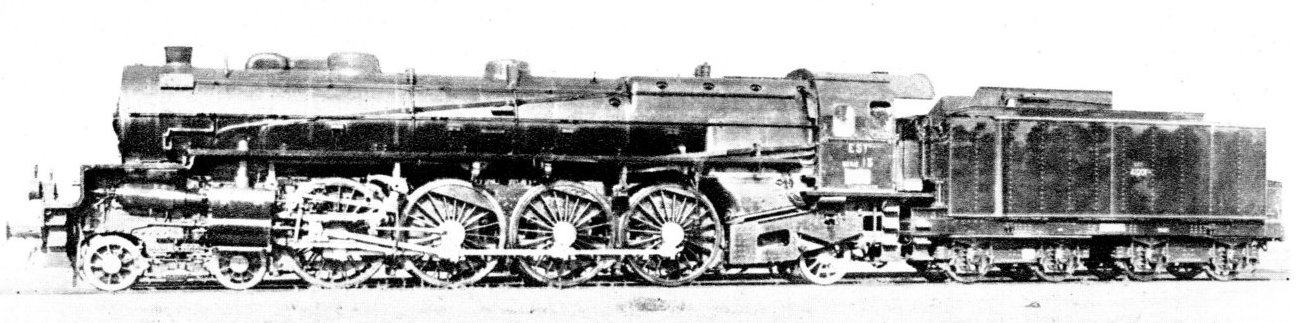

09. PACIFIC TYPE, FOUR-CYLINDER

LOCOMOTIVE, No. 6201, "PRINCESS ELIZABETH," LONDON, MIDLAND &

SCOTTISH RAILWAY.

09. PACIFIC TYPE, FOUR-CYLINDER

LOCOMOTIVE, No. 6201, "PRINCESS ELIZABETH," LONDON, MIDLAND &

SCOTTISH RAILWAY.

This

4-6-2 four-cylinder express locomotive, designed by Mr. W. A. Stainer,

was built at Crewe Works in 1933 for the London, Midland &

Scottish Railway, for working the Anglo-Scottish trains of 500 tons

between Euston and Glasgow. It has a tractive power of no less than

40,300 lbs., the boiler having a fire grate area of 45 sq. ft., and a

total heating surface, excluding superheater, of 2,713 sq. ft. The

working pressure of the boiler is 250 lbs. per sq. in. The two inside

cylinders drive the first pair of coupled wheels, while the outside

drive the middle pair. The cylinders are each 16¼in. diameter by 28in.

stroke, and the coupled wheels are 6ft. 6in. diameter. The weight of

the engine loaded is 104½ tons, and of the tender, 54 tons 2 cwts. The

overall length is 74ft. 4½in.

CHAPTER

2

PRESENT-DAY PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVES

DURING

the past ten years or so radical changes have been introduced in the

design of the steam locomotive, stimulated, no doubt, by the

competition of electricity and oil engines. The adoption of higher

working pressures seems to have opened up a new era not only in an

increase in the tractive power, but in efficiency also. When George

Stephenson built the Rocket

a

boiler pressure of 50 lbs. per sq. in. was employed, and pressures have

gradually increased until now there are many engines running in this

country working at 250 lbs. per sq. in.

The necessity for

greater locomotive power steadily increased, and engines have grown to

the maximum obtainable on the axle-loading permitted by the strength of

the permanent way and bridges, yet traffic needs more power. In the

latest types superheated steam is now universally used, considerably

increasing the efficiency of the locomotive with economies in the

consumption of fuel. Superheaters, as their name implies, are devices

for adding heat to the steam after it is generated, not only to remove

the moisture which ordinary saturated steam contains but of adding

sufficient heat to prevent condensation taking place in the cylinders,

where a portion of the energy is lost.

When increased train

loads demanded larger boiler capacity for the locomotives and a wider

fire-box, more weight had to be carried and more wheels were necessary,

consequently as the grate could no longer be accommodated between the

drivers a small pair of trailing wheels became indispensable.

This fact formed the basis of the design by H. A. Ivatt, locomotive

engineer of the G.N.R., for the first Atlantic or 4-4-2

type express engine in this country—No.

990 (now No. 3990 of the London & North Eastern Railway). The

main

characteristics are outside cylinders, two pairs of coupled wheels,

with a four-wheeled bogie at the leading end and a pair of trailing

wheels under the fire-box.

These engines were forerunners of the later Atlantics

with larger and wider fire-box boilers with 31 sq. ft. grate area, the

first of which, No. 251, left Doncaster Works in 1902. For over twenty

years they were the standard express engines of the G.N.R., and even

now they are to be seen working some of the fastest trains on the L.

& N.E. system, including the Queen of Scots

Pullman and the Harrogate and West Riding expresses.

Recent

passenger locomotives are for high speed express services, the speeding

up of which reflect their efficiency. We may take, as typical of these

locomotives, the 4-6-0 Royal

Scot, of the L.M. & S.R., 4-6-0 King George V, of

the G.W., 4-6-0 Lord

Nelson, of the Southern, and 4-6-2 Flying Scotsman

of the L. & N.E.R. The first named has three cylinders only,

18in.

in diameter ; the second and third have four cylinders, 16¼ and 16½in.

diameter respectively, two outside and two inside, while the fourth has

three cylinders, 20in. diameter.

These locomotives are fine

specimens of design, and well up to their work with the heaviest

trains. If still more powerful engines are needed, it is due to the

gradients which have to be climbed at some points. The ideal engine is

one that can take trains without help over these grades.

In 1927

the L.M. & S.R. decided to provide a more powerful locomotive

for

dealing with heavy through passenger trains by the West Coast route,

between London and Edinburgh, 400 miles, and Glasgow, 401½ miles, and

also for other main line sections of the system. With this end in view,

a three-cylinder simple-expansion superheated engine of the 4-6-0 type

was designed of sufficient capacity. The inside cylinder drives on the

crank axle of the leading pair of driving wheels and the two outside

cylinders the middle pair. The first of the series—No.

6100—was

named Royal Scot

and this

title has been applied to the whole of the class. There are seventy of

these engines in service; the first fifty were built in 1927 by the

North British Locomotive Co., and numbered 6100 to 6149 inclusive, a

further series of twenty engines, numbered 6150 to 6169, built in the

Company's workshops at Derby followed in 1930. These engines carry a

working pressure of 250 lbs. per sq. in. The three cylinders are each

18in. diameter by 26in. stroke, and the coupled wheels are 6ft. 9in.

diameter. The tractive efffort is 33,150 lbs.

In order to permit

locomotives to haul long distance non-stopping trains, water troughs

are provided at intervals which vary from 25 to 60 miles apart. This

arrangement enables water to be picked up without stopping by water

scoop apparatus fitted on the tender and operated by hand-screw gear.

By this means 1,500 gallons of water can be picked up in 20 seconds.

These troughs have on the average a length of 440 yards, and are

automatically refilled from tanks at the side of the line. This system

of replenishing locomotives with feed-water was devised by the late

John Ramsbottom, of the L. & N.W.R., back in the 'fifties.

The

L.M. & S. main line between Lancaster and Carlisle, rising from

sea-level to 915ft. up, at Shap Summit, is 32 miles and is a severe tax

on locomotive capacity. When the load exceeds thirteen coaches the Royal Scots take an

assistant engine over this gradient, which for four miles is at 1 in 75.

It will be remembered that the engine Royal Scot

was shown at the Century of Progress Exhibition, Chicago, in 1933,

after an exhibition tour of the principal cities of Canada and the

United States. To conform to American requirements, the engine was

fitted with a large electric headlight, as well as a warning bell,

which is still carried on the front end. Some of these engines bear the

names of famous regiments in the British Army, whilst others perpetuate

the names of celebrated engines of the past.

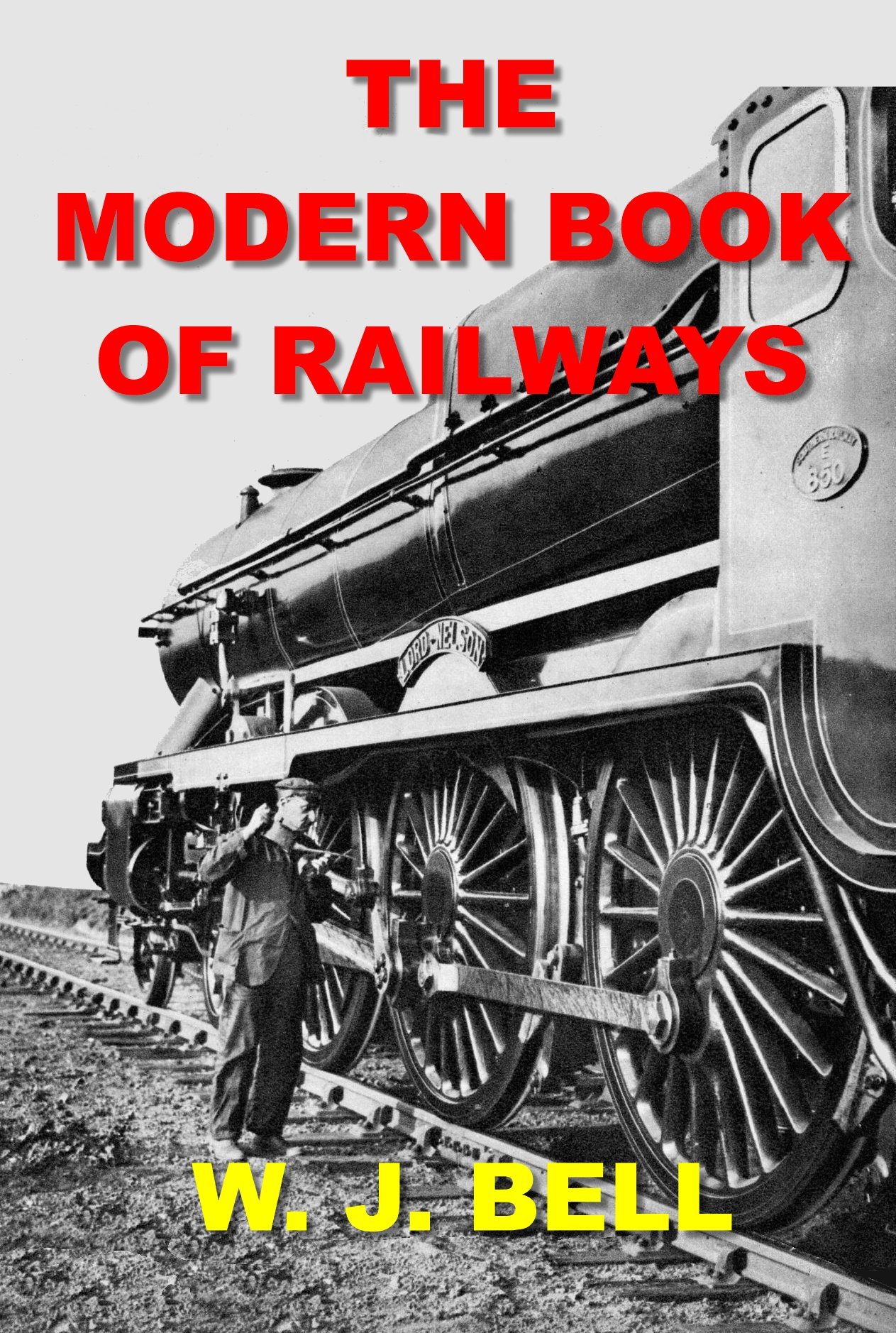

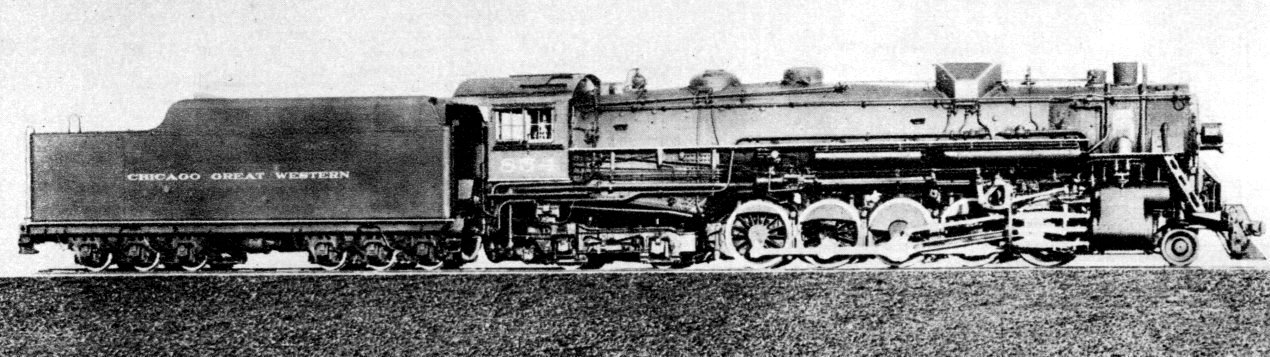

The L.M. &

S.R., in 1933, completed at Crewe Works the first two of a new class of

passenger locomotives of the "Pacific" type—the Princess Royal (No.

6200), and Princess

Elizabeth

(No. 6201), designed by Mr. W. A. Stanier, chief mechanical engineer,

for service on the heaviest expresses between London and Scotland. They

are the most powerful passenger locomotives on the system, and share

with the "King" class of the G.W.R. the distinction of being the most

powerful six-coupled type (on a tractive effort basis) in the country.

Whereas

the maximum load for the "Royal Scot" type, unassisted has been 420

tons, the new engines take trains up to 500 tons without assistance.

The four cylinders are each 16¼in. diameter by 28in. stroke, and the

coupled wheels 6ft. 6in. diameter. The boiler has a firegrate area of

45 sq. ft., and a total heating surface (excluding superheater) of

2,713 sq. ft.; working pressure is 250 lbs. per sq. in. Development of

the high tractive effort of 40,300 lbs. has been made possible by the

employment, in conjunction with the large boiler, of the four-cylinder

simple expansion arrangement, providing good balancing with a load of

22½ tons on each of the driving axles. The tender—carried on three

axles with roller-bearing journals—carries 4,000 gallons of water and 9

tons of coal. Total weight of engine and tender in working order is 158

tons 12 cwts., and the overall length is 74ft. 4¼in. These engines make

the longest regular daily through locomotive journey, from London

(Euston) to Glasgow (Central) and vice versa, 401½ miles each day,

climbing en route Shap and Beattock summits of 915ft. and 1,014ft.

above sea-level, respectively.

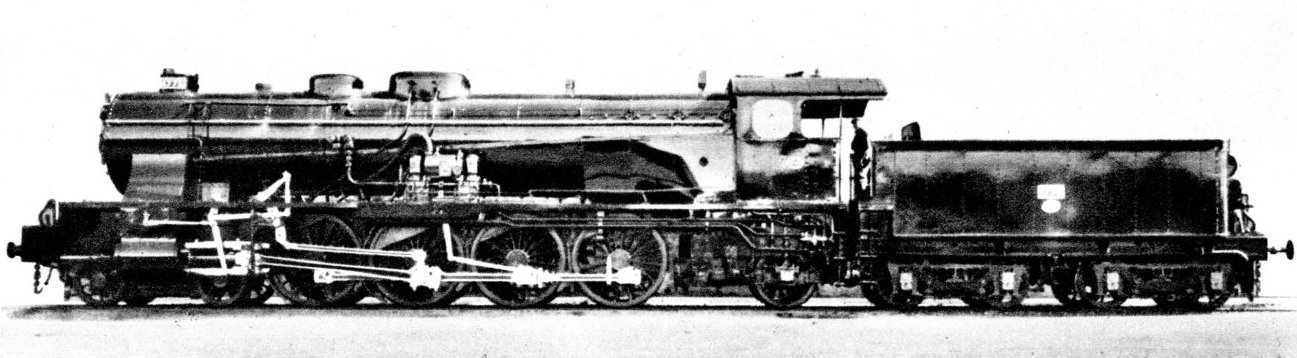

The

latest design of

three-cylinder 4-6-0 express engine of the L.M. & S.R. (5 X

class)

has a tapered boiler barrel, with a working pressure of 225 lbs. per

sq. in. The coupled wheels are 6ft. 9in. diameter, and the three

cylinders are 17in. diameter by 26in. stroke, with separate sets of

Walschaert valve gear. The boiler has an outside diameter of 5ft.

increasing to 5ft. 8⅜in., and is 13ft. 10in. in length. The feed water

is supplied through valves provided on top of the boiler. The roomy cab

has the driver's stand on the left-hand side, and is provided with

tip-up seats. The tender carries 3,500 gallons of water and 7 tons of

coal, although some have larger ones carrying 4,000 gallons of water

and 9 tons of coal. Total weight of engine and tender, loaded, is 134

tons 17 cwts.

The first of the G.W. four-cylinder 4-6-0 express engines of the

"Castle" class, the famous No. 4073, Caerphilly Castle,

was built at Swindon in 1923, and shown at the British Empire

Exhibition at Wembley of 1924. It is an enlargement of the earlier

4-6-0 express engines, with cylinders 16in. diameter by 26in. stroke.

It has a tapered boiler 5ft. 9in. diameter at the fire-box end, with a

length of 14ft. 10in. The coupled wheels are 6ft. 8½in. diameter. The

total heating surface is 2,312 sq. ft., and the grate area 30.28 sq.

ft. The working pressure is 225 lbs. per sq. in. The tractive effort is

31,625 lbs.

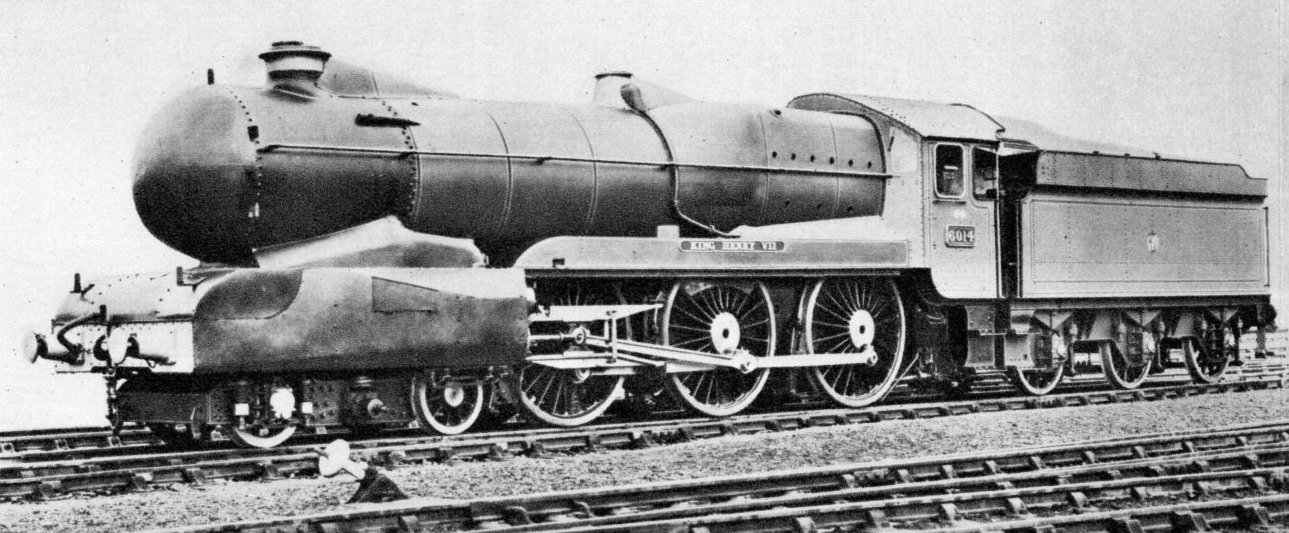

The "Castle" class proved very efficient, but a

later and heavier design is the much admired "King" type, first built

at Swindon Works in 1927, to the designs of Mr. C. B. Collett, chief

mechanical engineer. The two inside cylinders drive on the inside

cranks of the leading pair of wheels, and the outside pair are placed

farther back and drive on the outside cranks of the second coupled

axle. The four cylinders are each 16¼in. diameter by 28in. stroke; the

driving wheels are 6ft. 6in. diameter, and the tractive effort at 85%

of the boiler pressure is 40,300 lbs. The boiler has a conical barrel

16ft. long and 6ft. maximum diameter; the fire-box is of the Belpaire

type, 11ft. 6in. long outside, with a grate area of 34.3 sq. ft. The

heating surface is 2,514 sq. ft., and steam pressure 250 lbs. per sq.

in. The weight on each pair of coupled wheels is 22½ tons, and the

total weight 89 tons. The tender carries 4,000 gallons of water and 6

tons of coal. Total weight of engine and tender is 135.7 tons.

Designed

to keep time with trains weighing up to 360 tons on the heavy inclines

on the South Devon section of the main line, engines of both the

"Castle" and "King" classes have gained an excellent reputation for

efficiency in haulage, capacity and speed. One of the "Castle"

class—No. 5006, Tregenna

Castle—when

hauling the Cheltenham Flyer covered the 77.3 miles from Swindon to

Paddington in 56¾ minutes; 39 miles of this were run at an average

speed of about 90 m.p.h.

The first of the "King" class—No. 6000, King George V—was

sent to the United States to take part in the Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad Centenary celebrations, in 1927, and as a memento of the visit

was presented with a large brass bell, similar to those carried on

American locomotives, and this is still on the front buffer beam.

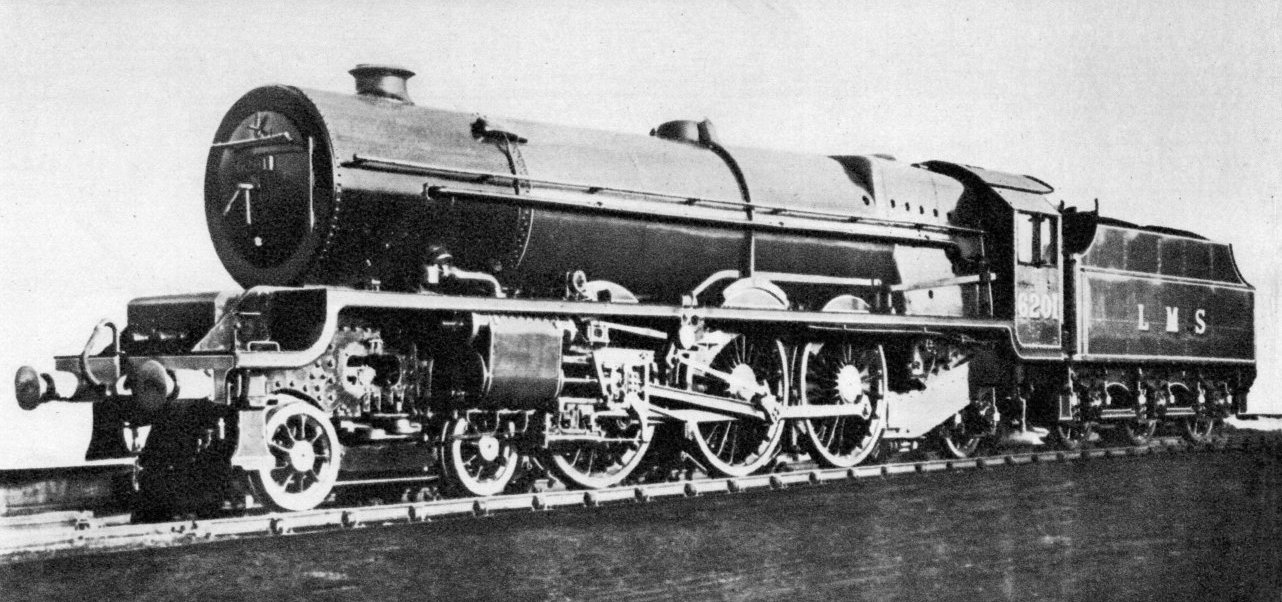

The

well-known "Lord Nelson" class engines of the S.R. will haul trains of

500 tons at an average speed of 55 miles an hour over any section of

the main lines. The four cylinders are all 16½in. diameter by 26in.

stroke, placed in line, the inside pair driving the first coupled axle

and the outside pair the second axle; each is actuated by separate

Walschaert valve gear. A peculiar feature of these engines is that, in

order to avoid a dead centre, the four cranks are set at an angle of

135° to each other. This means that four exhaust beats occur with every

revolution of the wheels. It is usual in four-cylinder engines to

simply duplicate the two-cylinder arrangement by setting all four

cranks at 90° to each other, but this still means only four efforts—or

exhaust beats—for each revolution, as in the two-cylinder type. In the

"Lord Nelson" class the cranks are so spaced that eight efforts, or

exhaust beats, are obtained per revolution, which means more even

turning effort. In other words, double the number—but smaller—efforts

are made during one revolution, and thus the stresses are not only

lower but more equalized, through each turn of the driving wheels, and,

consequently, there is less wear and tear throughout; also there is the

advantage of more even draught upon the fire, and conducive to better

combustion. The coupled wheels are 6ft. 7in. diameter, with a wheelbase

of 17ft., and the tractive effort is 33,510 lbs. The boiler has a

Belpaire fire-box; its total heating surface is 2,365 sq. ft., and the

grate area is 33 sq. ft. The working pressure is 220 lbs. per sq. in.

There

are sixteen of these engines in service between London (Victoria) and

Dover, and on the Bournemouth and Salisbury services from Waterloo.

The

bulk of the express services on the Dover, Bournemouth and Exeter main

lines of the S.R. is worked by the "King Arthur" class of 4-6-0

two-cylinder express locomotives, brought out in 1925. They are named

after the "Knights of the Round Table," and other characters mentioned

in the Arthurian legend.

Until the "Nelson" class was introduced

in 1926 they were the most powerful passenger engines on the Southern.

They have 20½in. by 26in. cylinders, and 200 lbs. per sq. in. boiler

pressure. To conform to the smaller loading gauge of the Eastern

section, modifications have been made in the shape of the driver's cab,

etc.

A number of really powerful locomotives of the 4-4-0 type,

with three cylinders, have been built since 1930 at the Eastleigh Works

of the S.R., for the main line routes to the Kentish coast resorts, as

well as to Portsmouth, where severe gradients and increasing weight of

modern rolling stock require their use. The restricted construction

gauge of the Hastings line necessitate them being as small and compact

as possible. These engines are named after famous public schools, hence

they are known as the "Schools" class.

Although not nearly as

large and heavy as the "Lord Nelson" and "King Arthur" classes, these

engines rank as the most powerful four-coupled type in the country. Due

to load limitations on the axles a round-topped fire-box was adopted

instead of the Belpaire pattern; this, however, permits a better

outlook for the driver. The three cylinders are each 16½in. diameter by

26in. stroke, and the driving wheels 6ft. 7in. diameter, spaced 10ft.

centre to centre. The piston valves are driven by three separate sets

of Walschaert valve gear. At 85% of the boiler pressure of 220 lbs. per

sq. in., the tractive effort is 25,130 lbs. The boiler barrel is 5ft.

5¾in. diameter and 11ft. 9in. long; its heating surface is 1,766 sq.

ft., and grate area 28.3 sq. ft. The superheater surface is 283 sq. ft.

The engine weighs 67.1 tons, of which 42 tons rest on the coupled

wheels. The tender carries 4,000 gallons of water and 5 tons of coal.

Between

1914 and 1922, seven large 4-6-4 type tank locomotives were built by

the L.B. & S.C.R. at Brighton Works. These conformed to the

construction gauge of the L.B. & S.C.R., which is larger than

of

other lines forming part of the S.R., and so confined their use to the

Brighton section. In view of the electrification of the lines from

London to Brighton, and Eastbourne, these engines were no longer

required for the work for which they were designed. They have,

therefore, been converted to 4-6-0 type tender engines at Eastleigh

Works. The first one dealt with is engine No. 2329, which bears the

name Stephenson.

The numbers and names allotted to the other six are: 2327, Trevithick, 2328 Hackworth, 2330 Cudworth, 2331 Beattie, 2332 Stroudley, and 2333

Remembrance.

A new cab with side windows has been fitted and also a shorter chimney,

enabling the engines to be used on almost any of the Southern main

lines. The main particulars are: cylinders, 22in. diameter by 28in.

stroke; coupled wheels, 6ft. 9in. diameter; boiler heating surface,

evaporative 1,816 sq. ft.; superheater, 838 sq. ft. Total 2,199 sq. ft.

Grate area, 26.6 sq. ft. Weight of engine in working order, 73 tons 9

cwts. The bogie tender carries 5,000 gallons of water, with a coal

capacity of 5 tons. Tractive effort is estimated at 25,600 lbs. Working

pressure has been increased to 180 lbs. per sq. in.

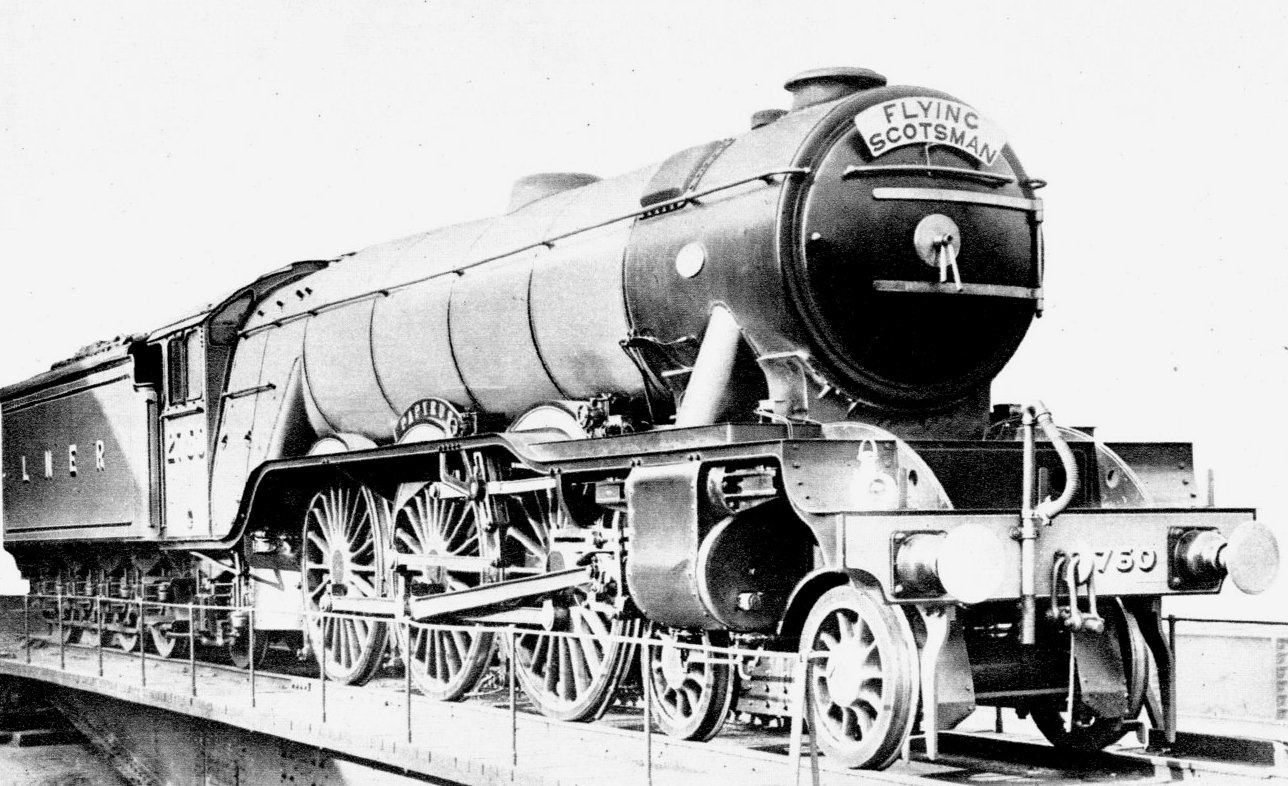

The

"Pacific," or 4-6-2 type engines of the L. & N.E.R., introduced

in

1922, work the express trains by the East Coast route to Scotland, and

during the summer cover the 392¾ miles between London and Edinburgh

without stop.

There are now seventy-eight of these engines in

service; all but six bear names after famous race-horses, the majority

of which have won the Derby or St. Leger. The striking features are the

large boiler and fire-box, in particular. The grate is wider than it is

long, with an area of 41¼ sq. ft. Further, the inner fire-box projects

forward into the boiler barrel, thus shortening the length between

tubeplates; the result is a fire-box with a heating surface of 215 sq.

ft. The boiler barrel is 5ft. 9in. diameter outside, at its least, and

6ft. 5in. at its largest diameter. Working pressure is 180 lbs. per sq.

in. The heating surface is 3,455 sq. ft., of which the superheater

contributes 525 sq. ft. Later engines of this type have been built with

boilers carrying 220 lbs. per sq. in. pressure. The engines detailed to

work the non-stop "Flying Scotsman" trains are provided with special

corridor tenders to enable the driver and fireman to be changed en

route. This tender runs on eight wheels, and carries 5,000 gallons of

water and 9 tons of coal. The total weight of engine and tender is 154

tons. These engines have 6ft. 8in. driving wheels, and three cylinders,

20in. diameter by 26in. stroke.

A good method of testing the

power of an engine is to work it on a road for which it had not been

specially built, thus the L. & N.E. and G.W.R., in 1925,

exchanged

locomotives for awhile. The G.W.R. Pendennis

Castle ran the "Flying Scotsman" between King's Cross and

York; and Victor Wild,

of the L. & N.E.R., the "Cornish Riviera" to Plymouth and back.

Both engines proved themselves able to deal efficiently with the

trains, and, although the G.W. engine was lighter and burned less coal,

general results were not decisive.

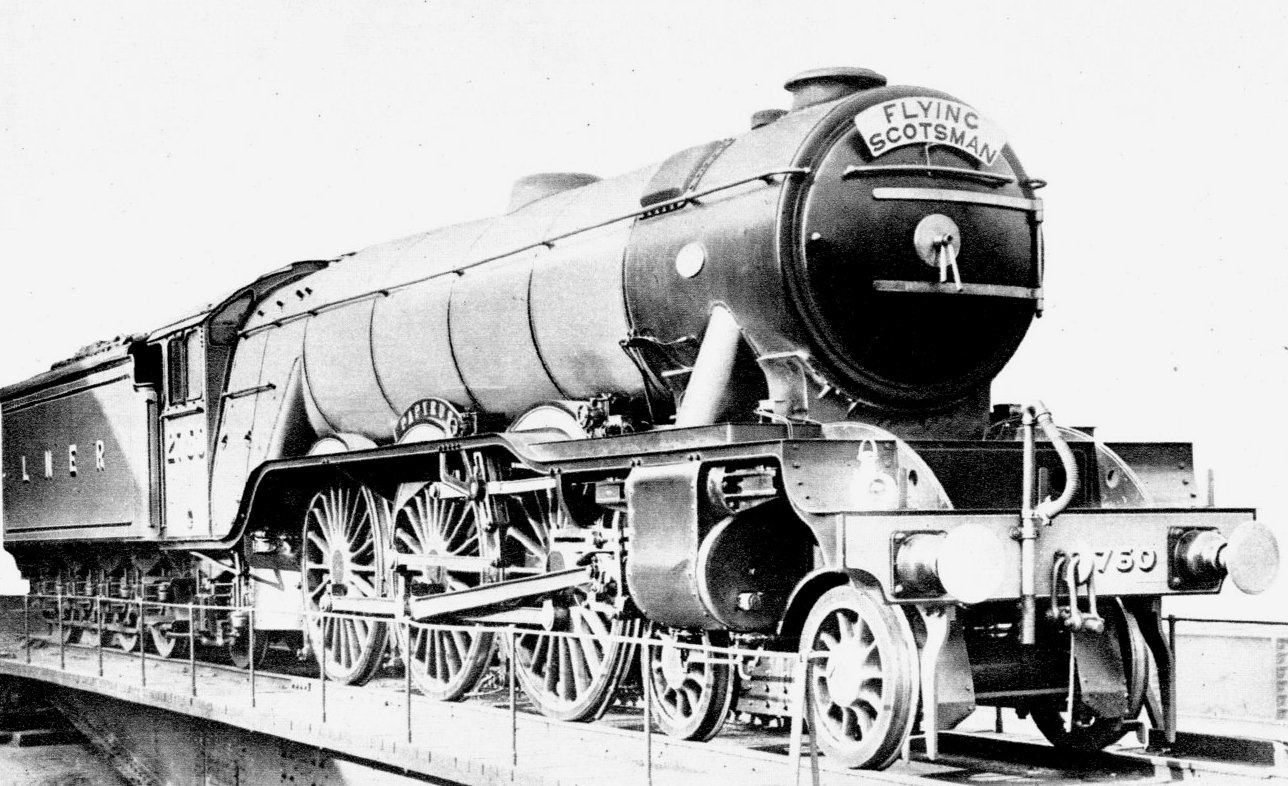

Mention should be made of a

remarkable test run made on November 30th, 1934, from King's Cross to

Leeds and back, with Pacific engine No. 4472, Flying Scotsman,

with a train of four vehicles, or about 145 tons. It left King's Cross

at 9.8 a.m. and arrived at Leeds (Central) 2 hrs. 32 mins. later, thus

achieving an average speed of 73.4 m.p.h. for the 185¾ miles. On one

stretch of 25 miles an average of 90½ m.p.h. was maintained. The return

journey, with six coaches attached, took 2 hrs. 37 mins., or 5 minutes

longer. Near Little Bytham a speed of 100 m.p.h. was attained. The

gradients run to 1 in 200 between London and Doncaster, and 1 in 100

thence to Leeds.

The L. & N.E.R. beat the world's record for

speed made by a steam train by running from London to Newcastle-on-Tyne

under four hours on March 5th, 1935, the distance being 268 miles. The

train was hauled by Pacific type engine No. 2750, Papyrus,

built in 1929, and comprised a dynamometer car, restaurant car, three

first-class corridor coaches, and brake van—a weight of 213 tons.

The

train left King's Cross at 9.8 a.m. and reached Newcastle at 1.4½ p.m.,

nearly 4 minutes ahead of schedule. As far as Doncaster, timings were

inside schedule, but owing to a derailment of some wagons at Arksey, it

was necessary to slow down and finally stop, because of single line

working ahead. In consequence, the train was a minute behind time

passing York (188 miles) in 2¼ hours, but at Darlington the lost time

had been regained; the average speed for the whole journey was 67½

m.p.h., or 68½ if 4 minutes is allowed for the Doncaster delay. The

highest speed recorded was 88 m.p.h.

At Gateshead sheds Papyrus

was found to be in excellent condition and at 3.47 p.m. the return

journey was begun. As far as Grantham schedule times only were kept, as

a long slack was necessary north of Doncaster, at the scene of the

derailed coal train, but after this driver Sparshatt took the

opportunity of showing what his engine could do. For twelve miles from

Corby and down the long drop from Stoke signal box to Tallington, the

average speed was over 100 m.p.h., whilst just south of Little Bytham

105.5 m.p.h. was registered for 30 seconds, and for 10 seconds it

reached 108 m.p.h.

The whole journey from Newcastle to King's

Cross was completed in 3 hrs. 51 mins. at an average speed of 69.6

miles an hour. The train had thus covered 536.4. miles in 7 hrs. 47½

mins.

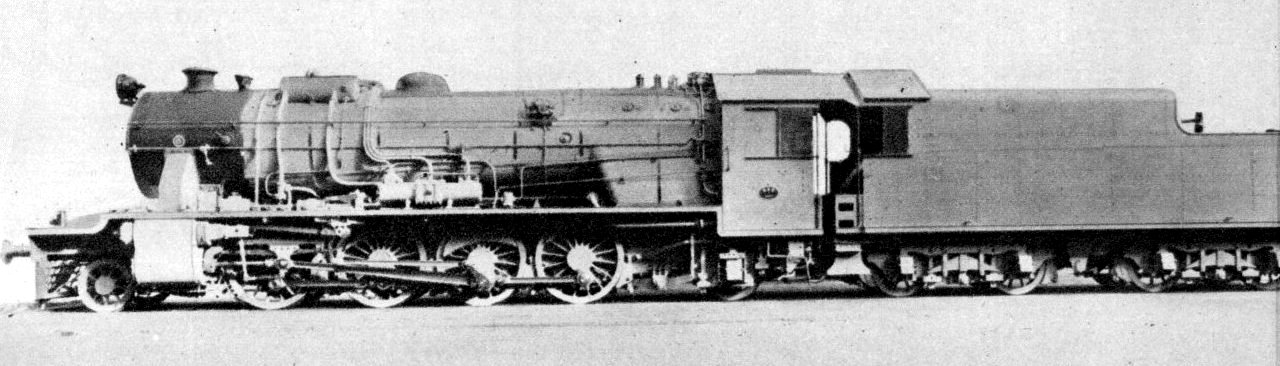

The latest design of express engine of the L. & N.E.R. is to

deal with the problem of working single-headed, trains up to 550 tons

over the Edinburgh-Aberdeen section, which abounds in heavy grades and

several speed restrictions, and needs spurts of high-speed to maintain

the running schedules. The 2-8-2 wheel arrangement has been adopted by

Mr. Gresley, so that the wheelbase has not been unduly protracted,

being only 2ft. 2in. in excess of the Pacifics. The apparent

streamlining effect is introduced mainly to raise the exhaust steam and

smoke clear of the driver's cab. The side sheets form a complete

covering, right up to the limits of the construction gauge of the

projections on the boiler barrel, and so prevent smoke eddies forming.

The long-shaped dome is covered, and acts as a steam collector,

communicating with the boiler by a number of slots; it also houses the

regulator. The grate area is 50 sq. ft., and this is the largest yet

provided on a British express locomotive. By using eight-coupled

driving wheels, a total adhesion of 80 tons 12 cwts. is obtained

without unduly loading individual axles. In working order the total

weight of the engine is 110 tons 5 cwts. Three cylinders, 21in. in

diameter and 26in. stroke, drive on to coupled wheels, 6ft. 2in.

diameter. With a boiler working pressure of 220 lbs. per sq. in., the

engine develops a tractive effort of 43,462 lbs.

The first of the class—No. 2001, Cock

o' the North—has cam-operated poppet valves and gear,

while the second, No. 2002, Earl

Marischal, has piston valves and Walschaert motion. The

tender, which accommodates 8 tons of coal and 5,000 gallons of water,

and is carried on eight wheels, weighs in working order 55 tons 6

cwts., so that the total weight of the engine and tender together

amounts to 165 tons 11 cwts.

To deal with the traffic requirements of East Anglia, a special design

of three-cylinder 4-6-0 engine was introduced by Mr. Gresley in 1928.

For its size and weight it is a powerful machine, and well suited for

the heavy gradients met with on the Great Eastern section. By

permission of H.M. the King, the first of the series, No. 2800, is

named Sandringham.

The remainder bear names of country seats, except No. 2845, which is

named the Suffolk

Regiment.

The diameter of 17½in. and the piston stroke of 26in. is common to all

cylinders. The drive is divided, the inside cylinder acting upon the

leading coupled axle, and the external pair upon the middle coupled

wheels. The boiler barrel is in two rings of 5ft. 6in. and 5ft. 4½in.

diameter, with a length of 13ft. 6in. The boiler pressure is 200 lbs.

per sq. in., and the tractive effort is 25,380 lbs.

For lighter main line and cross-country services, particularly in the

north-east of England and Scotland, Mr. Gresley introduced in 1927 a

class of powerful three-cylinder 4-4-0 express locomotives.

Twenty-eight of these symmetrical looking engines were built at

Darlington during 1927-28, and another eight in 1929, and named after

the "Shires." A further series of forty have been named after famous

"Hunts" in the districts served by the L. & N.E.R., whilst two

of the original set have been renamed after "Hunts."

The three-cylinders are in one casting, and are 17in. diameter, with a

stroke of 26in. Piston valves, 8in. diameter, with a maximum travel of

6in., are actuated by Walschaert motion for the outside cylinders, and

by Gresley gear for the inside valve, the levers for driving the latter

being arranged behind the cylinders and operated by the outside motion.

Six of the "Shire" series, and the whole of the "Hunt" class, have

cylinders served by poppet valves. The six "Shire" class engines have

poppet valves operated by Walschaert gear and oscillating cams; the

"Hunt" class have poppet valves operated by rotary cams. They have

coupled wheels, 6ft. 8in. diameter, carry a working pressure of 180

lbs. per sq. in., and have a heating surface of 1669.58 sq. ft., and

grate area of 26 sq. ft.

10. THE "TORBAY LIMITED"

EXPRESS, GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY, PASSING TWYFORD. (Photo: A. P. Reavil.)

At 12 o'clock noon, the down "Torbay Limited," one of the principal

trains of the Great Western Railway, leaves Paddington on its run of

199¾ miles to Torquay, where it is due at 3.35 p.m., maintaining an

average speed of 56.2 miles per hour. It is worked by locomotives of

the "Castle" or "King" class, and frequently comprises fourteen

coaches, weighing well over 500 tons. The running between Paddington

and Exeter, 179¾ miles in 169 minutes, averages 61.6 m.p.h.

There

are very few gradients worth mentioning on the run of the "Torbay

Limited," as from London to Reading it is nearly dead level, and thence

onward there are few trying grades other than the stiff climb from

Taunton up to Whitehall summit, so that this train is much easier to

work than the famous 10.30 "Cornish Riviera Ltd.," which has some

terribly hard climbs beyond Newton Abbot, with the load cut down to

eight coaches, or 300 tons.

11. THE "GOLDEN ARROW, PULLMAN,

LIMITED," SOUTHERN RAILWAY.

(Photo: H. G. Tidey.)

From Victoria Station, London, to Dover Marine Station, the distance is

78 miles, and the time scheduled 93 minutes, does not appear

particularly remarkable, but a congested and exacting road are reasons

why the running is not accelerated. The "Golden Arrow" is the British

portion of the Paris and London service of that name, and, when started

a few years back, was made up of Pullman cars only, but owing to the

falling off in Continental traffic now consists of four or five

Pullmans included in the ordinary 11 o'clock boat train, usually worked

by a "Lord Nelson" or "King Arthur" class engine.

12. "ROYAL SCOT"

TRAIN, LONDON, MIDLAND & SCOTTISH RAILWAY.

(Photo: H. G. Tidey.)

These expresses, which leave London and Scotland simultaneously at 10

a.m. every week-day, are made up of fifteen corridor carriages of the

most modern design, weighing about 417 tons, empty. Of these, nine work

between London and Glasgow (Central), and six to and from Edinburgh

(Princes Street). Running non-stop during the summer season from Euston

to Kingmoor (just north of Carlisle), 300 miles, engines are changed

here, and then a second stop is made at Symington to divide the train.

The 401½ miles between London and Glasgow are covered in 7 hrs. 40

mins., or at the rate of 52.4 miles per hour. In the return direction

the Glasgow and Edinburgh portions are combined at Symington, and the

next stop is at Carlisle (No. 12 signal box). The up train is due at

Euston at 5.40 p.m.

When the train is run in two sections,

the Symington stop is often omitted.

13. THE "FLYING SCOTSMAN,"

LONDON & NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY.

(Photo: H. G. Tidey)

Usually this famous train is made up of nine 60ft. cars, together with

a triplet restaurant car set, representing a load of 550 tons out of

London, when, in the summer, it makes its non-stop run between the

capital cities of England and Scotland, 392¾ miles, both north and

south in 7½ hours; the average speed is 52.4 miles per hour throughout.

Corridor

tenders are provided, so that a relief crew is carried, and a

changeover made half-way. The tender carries 5,000 gallons of water,

and picks up as much again from the six water troughs laid down on the

way. The equipment of the train includes a Louis XVI restaurant car,

electric kitchen, ladies' retiring room, hair-dressing saloon, and

Vita-glass windows.

14. THE "WEST RIDING PULLMAN"

EXPRESS, NEAR POTTERS BAR, LONDON & NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY.

(Photo: E. R. Wethersett.)

Made up of seven or eight Pullman cars, weighing between 300 and 340

tons, the "West Riding Pullman" is made up of two portions—King's Cross

and Halifax (202¾ miles), and King's Cross and Newcastle, via Harrogate

(280¾ miles), dividing at Wakefield. It leaves King's Cross at 4.45

p.m. every week-day and, after making four stops, completes the journey

to Halifax in 4 hrs. 12 mins., and to Newcastle in 5 hrs. 38 mins.

On Sundays its place is taken by the "Harrogate

Sunday

Pullman," non-stop to Leeds, where division takes place so as to serve

Harrogate and Bradford.

These trains are amongst

the fastest on the London & North Eastern Railway system, and

are

usually worked by the very efficient "Atlantic" type engines of the

erstwhile Great Northern Railway.

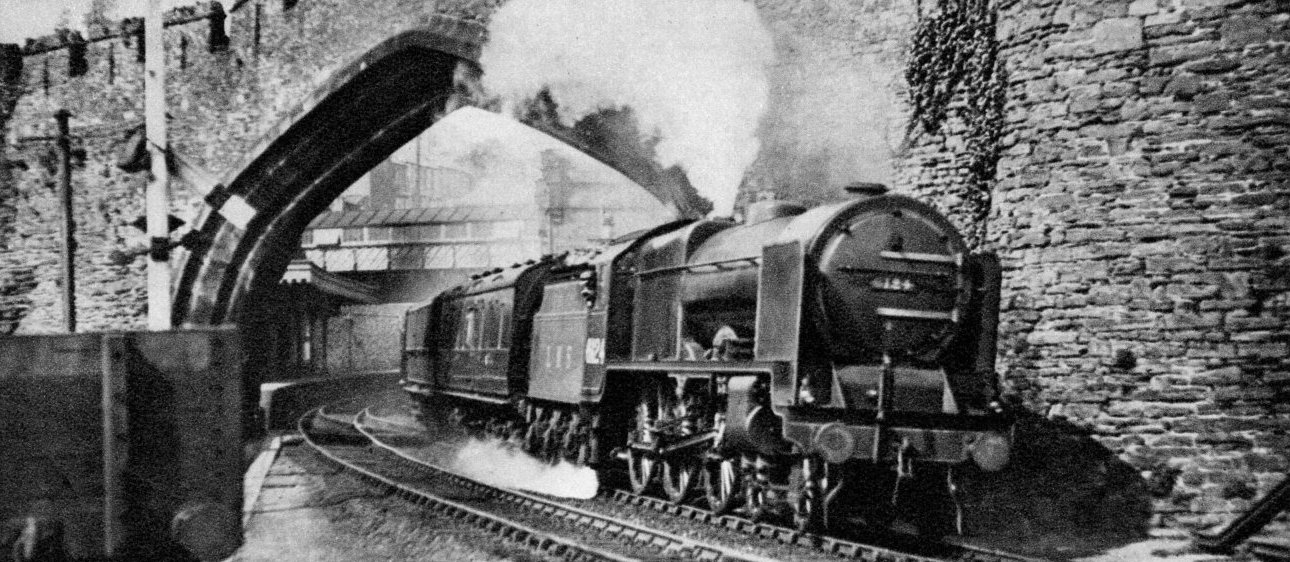

15. THE "IRISH MAIL" PASSING

CONWAY, LONDON, MIDLAND & SCOTTISH RAILWAY.

Between Euston and Holyhead—263¾ miles—there

are two "Irish Mail" trains each way on week days, for the steamers to

Kingstown, for Dublin. The trains are usually worked by 4-6-0,

three-cylinder engines of the rebuilt "Baby Scot" class, with 6ft. 9in.

drivers, which work at the high pressure of 200 lbs. per sq. inch. The

cylinders are 18in. dia. x 26in. stroke.

After

mounting the incline from Euston to Camden, the grading of the line all

the way to Holyhead is particularly good and the running easy, so that

in spite of the heavy loads, remarkably good time-keeping is the rule.

En route from Chester, the Conway river and the Menai Straits are

crossed by iron, tubular bridges. The latter, Robert Stephenson's

famous Britannia Bridge, is carried on three towers, the centre one

built on the Britannia rock, and 230ft. in height. The two main spans

are no less than 460ft. long, while the distance above water level is

more than 100ft.

The illustration shows the day "Irish

Mail" passing the picturesque ruins of Conway Castle.

CHAPTER

3

MODERN MIXED TRAFFIC, GOODS AND

TANK ENGINES

TWO

main considerations have governed the locomotive construction policy of

the British railways during recent years; first, reliability, in order

to obtain by more intensive use a greater revenue-earning mileage, and

secondly, the development of a locomotive which can appropriately

handle both passenger and freight trains.

Mixed traffic engines,

as they are termed, are generally of the 2-6-0 type and, although they

rarely have large driving wheels, can travel at fairly high speeds. The

majority have outside cylinders, whilst a number on the L. &

N.E.

and S. Rys. are of the three-cylinder type. Until recently the

standard, L.M. & S. mixed traffic engines, introduced in 1926,

had

the cylinders slightly inclined, which enabled them to be set higher

than the cranks, to clear station platforms, which they slightly

overlap. The later designs, with a higher pressure of 200 lbs. per sq.

in., have horizontal cylinders of smaller bore but providing a similar

tractive effort.

The first 2-6-0 engines of a definite mixed

traffic character appeared on the Great Western in 1910. Coupled wheels

of 5ft. 8in. diameter enable a good speed to be obtained on passenger

services, and sufficient power to be developed to work fairly heavy

goods trains.

Another numerous class of Great Western engine of

the 4-6-0 two-cylinder type with 6ft. wheels, introduced in 1928, has

proved very efficient for hauling excursion trains, as well as fast

freight; these bear names of famous "Halls" on the Great Western line.

They have 18½in. by 30in. outside cylinders, and carry a working

pressure of 225 lbs. per sq. in.; the tractive effort is 27,275 lbs.

The boiler is of the taper pattern, with Belpaire fire-box and

top-feed. Audible signalling apparatus is fitted in the cab for use

with the automatic train stop installation, with which the Great

Western main lines are now equipped. Other particulars are: total

heating surface, 2,104. sq. ft.; grate area, 27.07 sq. ft. The engine

in working order weighs 75 tons, and the tender, when loaded with 3,500

gallons of water and 6 tons of coal, 40 tons.

Mention should

also be made of the "4700" class of Great Western 2-8-0's. These

engines are exceptional, as they are the only ones in this country with

coupled wheels of a diameter of 5ft. 8in.

A numerous and very

efficient class of 2-6-0 mixed traffic engine is adopted by the S.R.

for fast goods trains to and from Southampton and the West of England,

and on the Eastern section also, as well as for excursion traffic when

required; on the heavily-graded lines west of Exeter they are used for

all classes of traffic. These have driving wheels, 5ft. 6in. diameter

and cylinders 19in. by 28in. They carry a working pressure of 200 lbs.

per sq. in.

For heavy goods trains hauled at moderate speeds,

small wheels are better adapted to the class of traffic. By coupling

the wheels with side rods the power exerted by the cylinders is

communicated to all the wheels at once; the larger the number of

coupled wheels the better the adhesion which the engine gets on the

rail. To provide sufficient tractive effort, a boiler that will

generate enough steam must be provided, and, to spread the weight over

a fair length of line, the engine must be sufficiently long.

Until

recent years the standard freight and shunting engine design of the

British railways has been the six-coupled or 0-6-0 type, and as a proof

of their general utility are still being constructed as a general

standard for the L. & N.E. and G.W. Rys. The latest examples on

the

former and used for mineral traffic in the Fife and Edinburgh districts

are of the "J 38" class, which have coupled wheels, 4ft. 8in. diameter,

and cylinders 20in. diameter by 26in. stroke. Another 0-6-0 class, the

"J 39," with larger wheels, 5ft. 2in. diameter have proved most useful

with fast goods or excursion traffic.

The

G.W.R., in 1930, built twenty 0-6-0 engines for light main line traffic

and branch line services. These engines have taper boilers and large

cabs, with side windows and up-to-date equipment, including audible cab

signalling apparatus. They have inside cylinders, 17½in by 24in.;

coupled wheels, 5ft. 2in. diameter, and work at a pressure of 200 lbs.

per sq. in. The tractive effort is 20,155 lbs.

A large number of

0-6-0 superheater goods engines were built from 1911 onwards for the

Midland Railway, and its successors, the L.M. & S.R., to the

designs of Sir Henry Fowler, then chief mechanical engineer. They have

two inside cylinders, 20in. diameter by 26in. stroke, with six-coupled

driving wheels, 5ft. 3in. diameter, on a wheelbase of 16ft. 6in. The

tractive effort at 85% of the boiler pressure is 24,555 lbs. The boiler

has a total heating surface of 1,410 sq. ft., and a grate area of 21.1

sq. ft., the steam pressure being 175 lbs. per sq. in.

The L.M.

& S.R. have thirty-three Beyer-Garratt articulated locomotives

of

the 2-6-0 + 0-6-2 type, for hauling coal trains between Toton, in

Derbyshire, and Brent sidings, near London, a distance of 126 miles on

a schedule of under 8 hours. These are powerful machines, with a light

axle loading, thus obviating strengthening many of the bridges on the

Midland division. Each engine has four cylinders, 18½in. diameter by

26in. stroke, with driving wheels, 5ft. 3in. diameter. The steam

pressure is 190 lbs. per sq. in., and the tractive effort 45,620 lbs.

Each

of the L.M. & S.R. Beyer-Garratts replaces two ordinary

locomotives

while hauling trains of about 1,400 tons weight, or 90 loaded wagons.

On the return journey they take 100 empty wagons (train limited in

length). These engines have an overall length of 87ft. 10½in., and

weigh 145 tons 14 cwts. A curious arrangement of barrel-shaped coal

bunker is provided on these engines. The coal is put into a large

cylinder, which slopes slightly towards the foot- plate. By turning a

handle in the cab the bunker starts to revolve, bringing down the coal

to the front, where the fireman can easily deal with it with his shovel—this

tends to lighten his labour; the turning is effected by a small steam

engine. Being covered in, no coal dust from the bunker is blown into

the cab when the engine is running bunker first.

For ordinary

goods and the mineral traffic from South Wales, "Consolidation," or

2-8-0 type locomotives are preferred by the Great Western, and for the

Derby and Nottingham coal trains to London by the L. & N.E.R.,

whilst the L.M. & S.R. are also using some of this type.

The

Great Western 2-8-0 engines were put into service in 1903, and were the

first of the type in this country. They have 4ft. 7½in. diameter

wheels; outside cylinders, 18½in. by 30in. and taper boilers. They work

at 200 lbs. pressure, and have 2,143 sq. ft. of heating surface. Later

ones have 225 lbs. pressure. The latest L. & N.E.R.

Consolidations

have three high pressure cylinders, all 18½in. by 26in. stroke; 4ft.

8in. diameter coupled wheels; and boilers 5ft. 6in. diameter, and on

the main line are rated to haul 80 wagons of coal (1,300 tons) from

Peterborough to London. The L.M. & S.R. has a large number of

0-8-0

type engines, as also has the L. & N.E.R. The L.M. & S.

engines

have inside cylinders, 19in. by 26in., and coupled wheels, 4ft. 8½in.

diameter. Boiler pressure 200 lbs. per sq. in. Tractive force, 28,250

lbs.

Designed to haul mineral trains of 100 loaded wagons, or

1,600 tons, on the Great Northern main line, two engines of the

"Mikado," or 2-8-2 type, Nos. 2393-4., built at Doncaster in 1925, were

the first of the type in the British Isles. Further, they were each

fitted with an auxiliary "booster" engine, working on the trailing

wheels, to assist the locomotive when starting, or ascending the

heavier gradients. These locomotives have three cylinders, 20in. by

26in. stroke. The coupled wheels are 5ft. 2in. diameter, or 6in. larger

than the 2-8-0 engine of 1921, and a higher speed can be attained. The

"booster" has two cylinders, 10in. diameter with a stroke of

12in., providing an additional tractive effort of 8,500 lbs. and making

the maximum tractive effort of the engine 47,000 lbs. The weight of the

engine and tender just exceeds 151 tons.

In 1919 Sir Henry

Fowler designed for the L.M. & S.R., for assisting trains up

the

Lickey Incline, between Cheltenham and Birmingham, two miles at 1 in

37, a large ten-coupled tender engine, with four cylinders 16¾in.

diameter by 28in. stroke, and 4ft. 7⅛in. wheels. Two piston valves only

are provided, operated by Walschaert valve gear. This engine weights

73¾ tons, and is the only ten-coupled engine in Great Britain.

Previously two 0-6-0 tank engines had to be used together for the

banking of heavy trains, but "No. 2290" does the work alone. The

incline mentioned is the steepest on any main line in the country, and

the engine spends all its working life running up and down this

two-mile stretch. A large electric headlight is used for "spotting" the

train to be banked up when coming on behind, as the engine is not

actually coupled to the train and just slacks off at the summit.

Tank locomotives are often employed on fast passenger as well as goods

trains, even for fairly long distances.

On

the G.W.R. the 2-6-2 arrangement was introduced in 1903. This engine

had 5ft. 8in. wheels, outside cylinders 18in. by 30in., taper boiler,

and tanks holding 1,380 gallons of water. A later series had larger

boilers and 2,000 gallon tanks. More recently they have all been fitted

with superheaters. Many are used for assisting trains through the

Severn tunnel. A later class—"4500"—first built in 1906, have 4ft.

7½in. wheels, outside cylinders 17in. by 24in., and tanks carrying

1,000 gallons of water. A similar, but still lighter, class for certain

small branches have 4ft. 1½in. wheels and 17in. by 24in. cylinders.

For

the L. & N.E.R. fast suburban traffic in the Edinburgh and

Newcastle areas and the services from Glasgow in connection with the

Clyde and Loch Lomond steamers a handsome tank engine of similar type

but with three cylinders was designed by Mr. H. N. Gresley, chief

mechanical engineer, and built at Doncaster in 1930 and later.

The

cylinders are each 16in. diameter by 26in. stroke, driving the second

pair of coupled wheels. Steam distribution is effected by Walschaert

gear to the outside valves and by the Gresley gear, operated by

extensions to the front of the outside valve spindles for the inside

valve. The coupled wheels are 5ft. 8in. diameter. The boiler, with a

working pressure of 180 lbs. per sq. in., is 5ft. diameter and 12ft.

2in. long.

The Great Western put into service in 1910 a 2-8-0

tank engine, known as the "5200" class, for dealing with the coal

traffic in South Wales from the pits to the port of shipment. Owing to

the falling off in the export trade they were not required for this

service, and have been converted at Swindon to the 2-8-2 type, having

larger coal and water capacity to make them suitable for main line

mineral service. They have two cylinders, 19in. diameter by 30in.

stroke; driving wheels, 4ft. 7½in. diameter; boiler pressure 200 lbs.

per sq. in. Tractive effort, 33,170 lbs. Water capacity of tanks, 2,500

gallons. Weight in working order, 92 tons 12 cwts.

An example of

the efforts made to improve the working conditions afforded enginemen

will be appreciated by comparing some of the old engines referred to

earlier in this book and the modern 2-6-4 type tank engines for fast

suburban services of the L.M. & S.R. A closed-in cab, with

let-down

windows, is provided, while the sides of the coal bunker have been

"flared" to give perfect visibility when running bunker first. There is

also a "sunshine roof," or sliding panel, in the roof of the cab, for

extra ventilation in hot weather. This engine has two cylinders, 19in.

diameter by 26in. stroke ; driving wheels, 5ft. 9in. diameter; boiler

pressure, 200 lbs. per sq. in.; tractive effort, 24,600 lbs.

CHAPTER

4

SOME

UNUSUAL TYPES OF STEAM LOCOMOTIVES

CONVENTIONAL

designs of steam locomotives are usually described by a distinctive

name, such as "Mogul," "Consolidation," "Mikado," "Atlantic,"

"Mountain," "Pacific," etc. The distinctive name is generally followed

by figures, which denote the arrangement of the wheels by what is known

as the "Whyte" numerical system of classification. Commencing at the

front, the wheels are divided into three groups: leading bogie, or pony

truck; driving wheels, and trailing truck, or bogie, wheels. Thus the

numerical classification of a "Mogul" locomotive is 2-6-0, indicating a

two-wheeled pony truck, six-coupled driving wheels and no trailing

wheels. A "Mikado" 2-8-2 signifies a two-wheeled bogie truck, eight

driving wheels and a two-wheeled trailing truck, and so on.

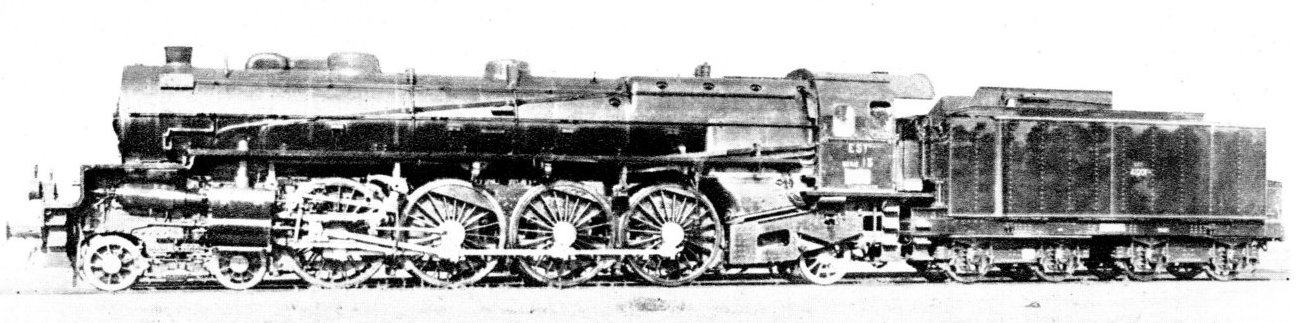

There have been many ingenious efforts to depart from traditional

designs in a desire to effectively deal with the conditions.

Gear-driven

locomotives built by the Sentinel Waggon Works for pick-up goods trains

and shunting duties, have unusual features. A vertical boiler carrying

a high working pressure, mostly 275 to 300 lbs. per sq. in., supplies

steam to one or more high-speed steam engines with vertical cylinders

and poppet valves. The engines drive a jack-shaft through gearing, and

from there one pair of wheels is driven by a pair of chains, whilst the

two pairs of wheels are coupled by a pair of chains instead of by side

coupling rods.

A novel development of this principle is embodied

in some gear-driven locomotives for a metre gauge railway in Colombia,

with steep gradients. The main frame carrying the boiler, tanks,

bunker, cab, etc., is mounted on two six-wheeled bogies. Each of the

six axles is separately driven through gearing by a small steam engine

mounted on the bogie. Separate flexible steam pipes with ball joints

connect each engine with a main throttle valve, and allow for movements

of the engine. Each engine is a double-acting compound with cylinders

4¼in. and 7¼in. diameter by 6in. stroke, driving a crank shaft carrying

at its centre a pinion which meshes with a gear wheel on the centre of

the corresponding axle; the ratio is 2.74 : 1.

As steam is

generated in a water tube boiler at the high working pressure of 550

lbs. per sq. in., ingenious arrangements are made to reduce this to 140

lbs. before it is admitted to the low-pressure cylinders when starting

up. Steam is taken to each engine from a main throttle, and to ensure

individual control the poppet valve regulator closes on to a conical

seat and has a piston connection with six ports, each admitting steam

to one engine. The tractive effort is estimated at 17,500 lbs.; as all

axles are driven, a maximum adhesive weight is assured.

Among

notable high-pressure locomotives which have been produced in recent

years, the Delaware & Hudson Railroad had one built in 1924

with a

pressure of 350 lbs. per sq. in. This engine, named Horatio Allen,

is a two-cylinder compound with a 2-8-0 wheel arrangement, the tender

being fitted with a booster. The boiler followed usual practice, but

over it, on each side, two cylindrical drums are fixed. Two shorter

drums form the lower sides of the fire-box, the front wall being formed

by a flat water space with ordinary stays. The upper drums are

connected to this water space, and pass through it. The boiler barrel

is secured to the front wall of the water space; the rear plate of the

water space is cut away for the fire-box tube-plate which is fixed in

it, and the drums are attached to it. The back end of the fire-box is

formed by a similar flat water space into which the rear ends of the

four drums are secured. The top of the fire-box between the upper drums

is formed by water tubes connecting the front and back water spaces,

and each of the sides by two rows of curved water tubes joining the

upper and lower drums. The front ends of the upper drums are

connected to the boiler barrel by headers. With this boiler about

one-third of the evaporative heating surface is in the fire-box,

whereas in ordinary locomotive boilers the fire-box surface is only

about one-tenth of the total.

A similar engine was obtained in 1927 which was called John B. Jervis.

The pressure was raised to 400 lbs. per sq. in., and a greater

superheating surface given. This was followed in 1930 by another 2-8-0

compound fitted with a water-tube boiler of the same general design,

with a pressure of 500 lbs. per sq. in., and this was named James Archibald.

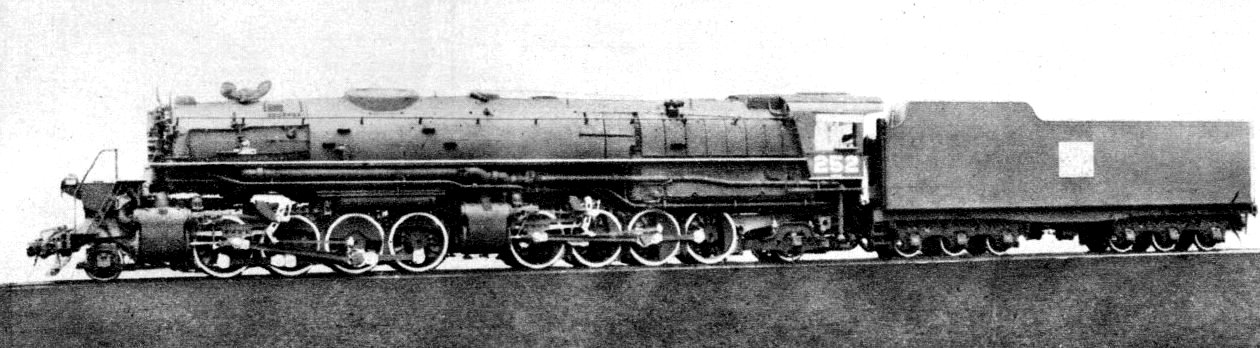

Following

these experimental locomotives, all of which have shown exceptional

thermal efficiency, the Delaware & Hudson Co. showed at the

Chicago

Exhibition of 1934 a 4-8-0 four-cylinder triple expansion locomotive,

No. 1403, L. F. Loree,

which

carries a boiler pressure of 500 lbs. per sq. in. This is the second

application of the triple expansion principle to a steam locomotive,

the first being the somewhat abortive experiments carried out on the L.

& N.W.R. in 1895. This engine of the D. & H.R.R. has

one

high-pressure cylinder, 20in. diameter by 32in. stroke, located under

the driver's side of the cab, one intermediate pressure 27½in. diameter

by 32in. stroke under the fireman's side, and two low pressure 33in. by

32in. in the orthodox position, under the smoke-box. All four cylinders

drive on the second pair of coupled wheels. Steam is distributed by

poppet valves to all cylinders. The boiler has a water tube fire-box

and a fire-tube barrel of relatively small diameter and completely

filled with water. The steam space is in the drums of the fire-box,

which are carried forward beyond the fire-box and connected to the

barrel near the front ends. In starting steam is fed to the

intermediate cylinder receiver direct from the high-pressure steam

chest through a spring loaded feed valve, which closes when a pressure

of 170 lbs. is reached in the receiver.

The coupled wheels are

5ft. 3in. diameter. The tender has one four- and one six-wheeled bogie,

the latter being fitted with an auxiliary booster engine, taking steam

direct from the boiler at 500 lbs. pressure. At starting, in simple

gear, the tractive effort is estimated at 90,000 lbs., and when working

triple expansion 75,000 lbs. When the booster is working at starting,

an additional tractive power of 18,000 lbs. is developed.

In the

experimental four-cylinder compound locomotive No. 10,000 of the L.

& N.E.R., built in 1929, it was decided to use a working

pressure

of 450 lbs. per sq. in., and adopt a Yarrow-Gresley water-tube boiler.

As its name implies, the water-tube boiler consists of a number of

tubes which carry the water, and which are surrounded by the hot gases.

The boiler has one top steam drum, 3ft. in diameter and 28ft. long, the

fire-box being formed of banks of tubes passing downwards to two lower

water drums, 18in. diameter and 11ft. long. The front part is formed of

further tubes passing to two water drums, 19in. diameter by 13ft. 6in.

long, placed at a higher level than the others. A superheater is fitted

in the front end of the main flue.

The high pressure inside

cylinders drive the front coupled axle, and are placed well forward,

while the low-pressure outside pair drive the second axle. At starting,

steam limited to 200 lbs. pressure can be admitted to the low-pressure

cylinders. The tractive effort is estimated at 32,000 lbs.

The

main particulars are: cylinders, two high-pressure, 10in. diameter by

26in. stroke; two low-pressure, 20in. diameter by 26in. stroke; coupled

wheels, 6ft. 8in. diameter; carrying wheels, front and rear, 3ft. 2in.

diameter. Total heating surface, 2,126 sq. ft. As the top of the boiler

is carried to the limit allowed by the loading gauge, no chimney can be

permitted to project above it, and this is concealed except in a front

view, by two metal wings formed by an extension of the smoke-box.

In

1920 an experimental geared steam turbine condensing locomotive built

by the Aktiebolaget Ljungstroms Angturbin, near Stockholm, was tried

out on the Swedish railways. This comprised two vehicles, one of which,

with a two-axle bogie and three carrying axles, takes the boiler, and

the other, with three motor axles and one truck axle, takes the main

driving machinery and condensing plant.

The locomotive boiler has a heating surface of 108 sq. ft. in the

fire-box and 1,130 sq. ft. in the tubes, with a grate area of 28 sq.

ft. and a working pressure of 300 lbs. per sq. in. It is fitted with a

superheater and with a hot air induced draught apparatus, the air

heater for which is located beneath the front end of the boiler. The

driver's cab and the coal bunkers are placed saddlewise across the

boiler. The turbine is rated to develop 1,800 b.h.p. at 9,200

revolutions per minute, corresponding to a train speed of 68.3 miles an

hour, the power transmitted through gearing having a ratio of 22 to 1

to the six-coupled driving wheels by means of connecting rods.

Exhaust steam from the turbine is led to a receiver and thence to the

air-cooled surface condenser, consisting of flattened tubes in series,

the cooling air for which is supplied by fans. The condensate is

returned to the boiler by a boiler-feed pump through a series of

feed-water heaters, which receive the requisite supply of exhaust steam

from the auxiliaries at varying pressures, thus ensuring a high

temperature of feed-water at the boiler. Under actual service

conditions the results appear to have been highly satisfactory and

showed a saving in fuel consumption of 50%.

In spite of its advantages, the complication and cost of the condensing

arrangement prevented a more extended adoption of this form of turbine

locomotive. The Ljungstrom Company therefore designed a non-condensing

locomotive, having a 2,000 h.p. turbine arranged in front of the

smoke-box and connected to the driving wheels by means of side rods

through a gear and jack-shaft arrangement. The engine is of the 2-8-0

type, with coupled wheels 4ft. 5⅛in. diameter, with a four-wheeled

tender, and is in service on the Grangesberg Railway, Sweden. Apart

from the turbine and its accessories, the design of the locomotive is

on similar lines to the orthodox reciprocating type engine. Steam from

the boiler at 185 lbs. pressure passes through a regulator in the dome,

thence through a superheater steam chest and strainer, to the admission

valve bolted to the casing of the turbine. This admission valve is

provided with five nozzles operated from the footplate. The regulator,

therefore, is only used as a main stop valve for the boiler, and is

opened full at the start of the run, and closed at the end. The

tractive force is 47,400 lbs.

16. SWING-BRIDGE OVER

THE GLOUCESTER & BERKELEY CANAL AT SHARPNESS, SEVERN &

WYE JOINT RAILWAY.

(Photo: Topical Agency.)

For the purpose of connecting the Severn & Wye Railway, in the

Forest of Dean district of Gloucestershire, with the former Midland

Railway at Sharpness, a remarkable bridge was built across the river

Severn, and opened in October, 1879. At the time of building it was,

with the exception of the Tay Bridge, the longest bridge in the

country, there being twenty-two spans. Two spans over the navigable

channel are 327ft. long, and there are also five spans of 171ft.,

fourteen of 124ft., and one of 200ft., the latter being shown in our

illustration. This is a swinging span over the Gloucester &

Berkeley Canal worked by a steam engine, housed on top of the girders.

The total length of the bridge is 1,387 yards, the width of the river

being 1,186 yards. The bridge carries a single line of railway, but the

swinging span has been built to accommodate two tracks, if necessary.

17. WHITEMOOR

MARSHALLING YARD, NEAR MARCH, LONDON & NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY.

(Photo: L.N.E.R.)

About thirty miles north of Cambridge, at Whitemoor, the London

&

North Eastern Railway have provided a concentration yard for dealing

with freight traffic from the coal producing and manufacturing

districts to East Anglia and London. The sidings illustrated deal with

the south-bound traffic. It consists of two main sections; ten

reception roads, into which the trains to be sorted are run on arrival,

and forty classification sidings, into which each train is sorted out,

and these two parts are connected by the "hump."

On

the arrival of a train, the shunter passes down the train, and makes a

list, noting the destination of each wagon, and marking the "cut"

according to the siding in which each wagon is to be dropped; at the

same time, he uncouples the wagons between the various cuts. He

despatches a copy to the control cabin, and a copy is also given to the

foreman at the top of the hump. When all is ready the shunting engine

commences to push the train up over the hump at such a speed that a

train of sixty or seventy wagons, having, say, forty cuts, can be

disposed of in six or seven minutes. The hump is designed to provide

momentum to carry wagons into the sorting sidings. Four hydraulic rail

brakes are provided at the foot of the hump, one on each of the first

four leads after the main points. They slow down the wagons, which are

travelling too fast, and keep a suitable spacing between them.

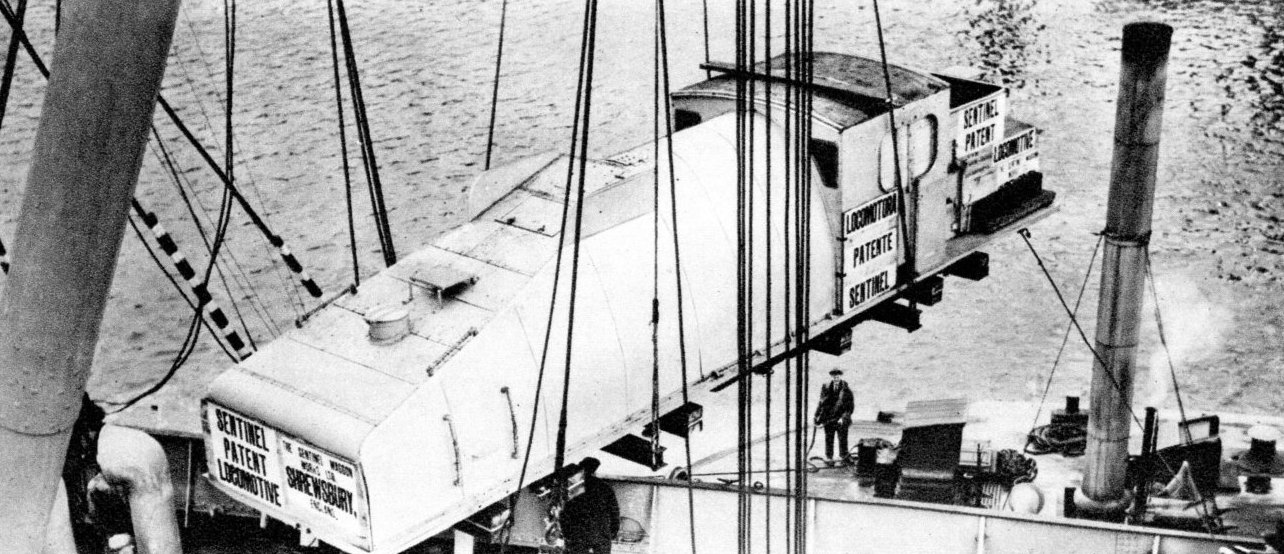

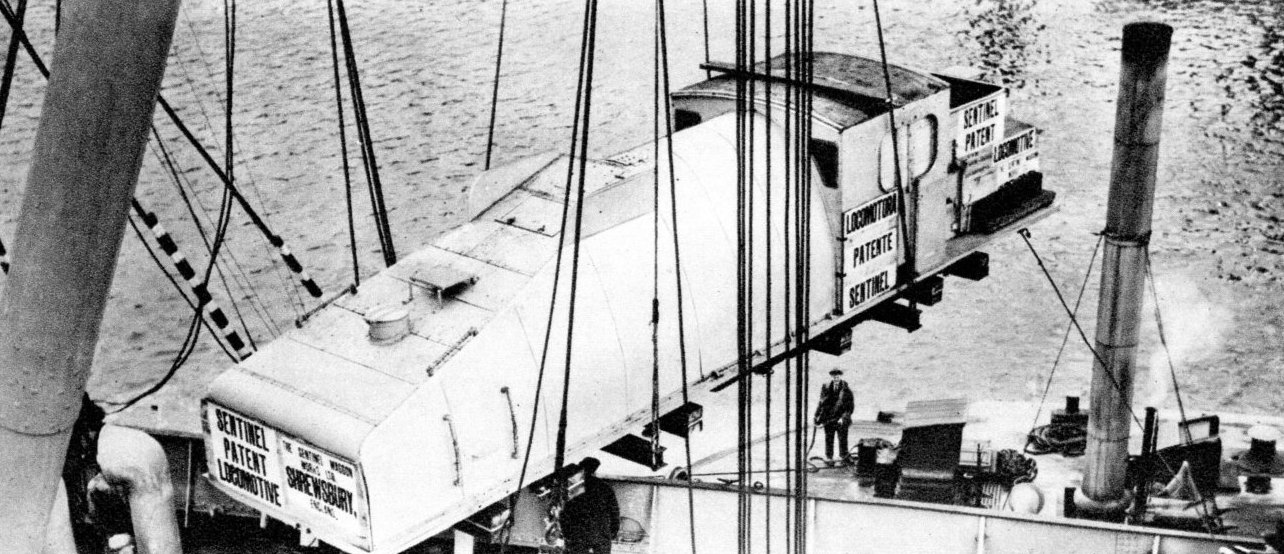

18. SHIPPING A

"SENTINEL" STEAM LOCOMOTIVE FOR SOUTH AMERICA.

(Photo: Sentinel Waggon Works.)

Of late years the usual practice in delivering locomotives for overseas

railways is to send them in shiploads, fully erected, ready to be put

into service immediately on arrival at destination.

The accompanying illustration shows a six-engined

Sentinel

steam locomotive being loaded for shipment to a metre-gauge railway in

Colombia, South America. It will be noticed this is being lifted by a

derrick on the vessel itself, capable of taking lifts up to 120 tons.

19. STREAM-LINED 4-6-4

TYPE LOCOMOTIVE, NEW YORK CENTRAL LINES, U.S.A.

The first American stream-lined steam locomotive has been named Commodore Vanderbilt,

after the founder of the New York Central Lines, and is of the

Central's famous 4-6-4 Hudson type of passenger locomotives. Both

locomotive and tender have been stream-lined in accordance with the

latest researches in aero-dynamic science. In addition to the wheels of

the tender and engine trucks, the 6ft. 7in. driving wheels are provided

with roller bearings.

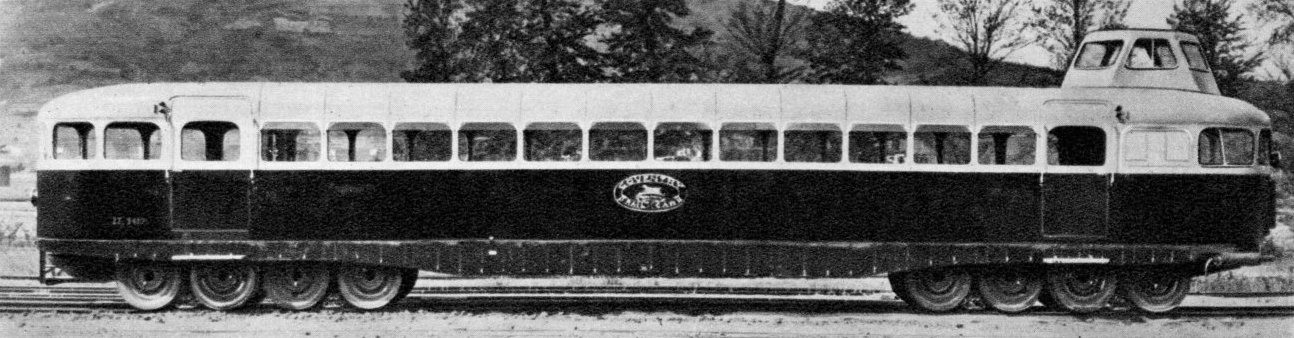

20. 240 H.P. COVENTRY RAILCAR ON

THE LONDON, MIDLAND & SCOTTISH RAILWAY.

One of the latest types of pneumatic tyred rail-car has recently been

brought over from France, and tried on the main line of the London,

Midland & Scottish Railway. It is a 56-seater, with a 240 h.p.

petrol engine and mechanical transmission driving on one of the two

eight-wheeled bogies. The wheels are fitted with pneumatic tyres,

having steel flanges, and any loss of pressure in a tyre causes a

hooter to sound in the driving cab. On a test run from Leighton Buzzard

to Euston, 40¼

miles, were covered in 42½

minutes, with a maximum speed

at Watford of 65 miles per hour. The running of the car is particularly

steady and silent.

21. ROYAL TRAIN, SOUTH

AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS.

When making his recent tour of the Australian Commonwealth, H.R.H. the

Duke of Gloucester travelled over the 5ft. 3in. gauge lines of the

South Australian Railways in a train replete with every possible

convenience. The lounge of the Royal Saloon is equipped with radio,

fans, clock and electric speedometer. It weighs 52 tons, and is

approximately 80ft. long. Adjoining the lounge are three sleeping

compartments, one having a beautifully appointed bathroom. The kitchen

is also nicely fitted up and provided with hot and cold water, a wood

burning stove, and an electric refrigerator of ample capacity. Finally,

the dining-room, which is of plain design, is well finished, and

lighted electrically by fittings flush with the roof of the car.

22. 6-CYLINDER GARRATT

LOCOMOTIVE, No. 2395, LONDON & NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY.

For "banking" heavy mineral trains on the Worsboro' branch, in South

Yorkshire, which has a gradient of 1 in 40 for two miles, the London

& North Eastern Railway use the most powerful locomotive in the

British Isles. This is of the six-cylinder Garratt articulated type,

built in 1925 by Beyer, Peacock & Co., Ltd., of Manchester. The

engine is of the 2-8-0 + 0-8-2 type, each unit being a 2-8-0

three-cylinder engine, with the same cylinders, valve motion, etc., as

those of the London & North Eastern Railway standard mineral

engines.

CHAPTER

5

LOCOMOTIVES FOR MOUNTAINOUS

COUNTRIES

POWERFUL locomotives are necessary in mountainous countries where steep

and long gradients are traversed. Besides special classes of huge tank

and tender engines, most of which have one or more pairs of wheels

without flanges to ease running on sharp curves, in many instances a

flexible or articulated type of locomotive is required to meet the

special conditions of working.

Ordinary adhesion steam engines are employed on the 1 in 25 grade

extending for 74 miles on the Callao-Oroya section of the standard

gauge Central Railway of Peru, on the 1 in 28 narrow gauge Darjeeling

Himalayan Railway, and on a 1 in 12 section of the Leopoldina Railway

of Brazil. There are quite a variety of articulated locomotives for

adhesion working, in which two or more units—each steam driven—are

connected together in such a way that one can take up an angular

position with respect to another section without difficulty when

rounding sharp curves, especially on lines which have heavy traffic

which must be hauled by large, long and powerful engines. In these

circumstances the articulated locomotive alone meets the

case.

The

"Fairlie" double engine, of which about half a dozen were built for

standard gauge railways in this country, in addition to a few for the

Festiniog Railway (1ft. 11½in.

gauge), provided a type with large

tractive force, capable of passing round sharp curves. The whole of the

weight was available for adhesion. The engine had a double boiler, each

part with an independent fire-box, both boxes being in one casing and

fired from the side. The boilers were carried on two steam bogies by

means of saddles under which the pivots formed part of the bogie

frames. The steam pipes were led into a special fitting forming a

prolongation of the lower part of the smoke-box. Here a swivelling and

sliding joint was provided through which steam passed to the cylinders

by the centres of the bogies where these pipes were articulated. Ball

and socket joints were also provided on the exhaust pipes. Many

"Fairlie" locomotives were supplied to Mexico, Burma, New Zealand,

Chili, Portugal, Russia, etc.

The "Mallet" locomotive, the most

highly-developed articulated locomotive in the world for heavy freight

service, was patented in the early 'eighties by Anatole Mallet, a

famous French engineer. In the "Mallet" engine, which is really a

semi-articulated one, the boiler and cab are fixed rigidly to the rear

motor bogie, the front motor bogie being close coupled to the rear

motor bogie by a vertical hinge pin, the centre of which is fixed at a

point midway between the two sets of wheels, thus assisting the guiding

of the rear bogie into curves. The boiler attached to the rear bogie

protrudes forward over the front engine, the weight being taken by

bearings on the front engine. A spring centring device on the boiler

bearing assists recovery on leaving curves. The cylinders are located

at the front of the motor bogies, the high pressure being fixed to the

rear unit, and thus integral with the boiler and the low-pressure

cylinders at the front of the engine. Large "Mallet" locomotives have

been built by Continental and British builders, but its great

development has been brought about in the United States. Long distances

between important centres and heavy traffics have fostered its adoption

there. Some large size "Mallets" of recent years are fitted with four

high-pressure cylinders.

On the Virginian Railroad are some huge

2-10 + 10-2 "Mallet" engines, built for working coal trains of nearly

5,000 tons on the heavy grades over the Blue Ridge Mountains. Since the

electrification of this line these engines act as bankers at the back

of 14,000 ton coal trains, which are headed by one of the most powerful

electric locomotives in the world.

The Erie Railroad have a

Triplex "Mallet"—that is, with three sets of coupled wheels—and on

a

test run it hauled a load of about 15,000 tons, but a banking pilot was

necessary to start the train.

Another articulated type is the

"Kitson-Meyer," the first of which were built in this country in 1894.

This has a single boiler carried by a girder supported by the steam

bogies. There are two sets of coupled wheels below it, each with its

own cylinders arranged at the outer ends of the bogies. In the early

"Meyer" locomotives the cylinders were located at the centre of the

engine. Among recent examples built for the Kalka-Simla Railway (India)

and the Colombian National Railways, the bogies are arranged well

apart, and special provision is made for ensuring maximum flexibility,

not only in the horizontal but in the vertical direction.

As a

special purpose articulated locomotive and a very efficient one,

mention should be made of the "Shay" locomotive, first built in 1880.

It is suitable for severe grades and sharp curves which cannot be

economically worked by the ordinary adhesion type locomotive. Designed

for duty in North American lumber camps it soon passed to other useful

spheres, and has been extensively used for contractors' work and

industrial establishments. In this locomotive the vertical engines are

placed on one side of the centre line for balancing purposes and are

strongly supported on the frame. Three cylinders are generally used, so

as to bring the setting of the cranks to 120 degrees. These drive on a crank shaft, which in

turn is connected with the main longitudinal shaft, which is built in

sections and rendered flexible by universal joints. The shaft drives

pinions which mesh with bevel wheels attached to the outer face of the

running wheels, so that every wheel is a driver. The engines are

situated alongside the boiler, the latter being placed "off centre"

sufficiently to balance the locomotive.

Combined rack and adhesion locomotives with two sets of engines are in

successful service on some lines. One pair of cylinders drives the

smooth wheels, and the second pair the rack mechanism, both sets being

worked simultaneously on rack sections requiring maximum tractive

power. On the Furka-Oberalp Railway (metre gauge), one of the few lines

still worked by steam locomotives in Switzerland, combined rack and

adhesion compound engines of the 2-6-0 type are used. In addition to

the three-coupled axles for work on the adhesion sections of the line,

driven by outside high-pressure cylinders, there are two inside coupled

axles supported by internal longitudinal framing for driving the rack

pinions; these are driven by the low-pressure cylinders placed inside.

The locomotive works as a "simple" engine on the adhesion sections of

the line, and as a compound on the rack sections. To provide sufficient

space for the large low-pressure cylinders the main framing is placed

outside the wheels.

Purely rack locomotives are used where the ruling grade is practically

continuous for the whole length of the railway. On the rack railways of

Switzerland and other mountainous countries the old system introduced

by Blenkinsop as far back as 1812 is revived. The object is the same,

namely, to increase the tractive power with the minimum dead-weight of

the engine. The rack is placed centrally between the ordinary rails,

and in the Abt system two rack bars (and sometimes three) are used, and

the method of laying these, one in advance of the other, differentiates

the position of the teeth, and ensures smooth running.

For the first rack mountain railway—that from Vitznau, on Lake

Lucerne—up the Rigi to Kulm, 5,905ft. above sea-level, a decided

variation from orthodox design was made in the special type of

locomotive, which like the railway itself was an entirely new

departure. It was provided with a vertical boiler set at such an angle

as to reduce, as far as possible, variations in the water level, due to

the difference in gradients. After a few years service, this vertical

boiler was abandoned in favour of the horizontal pattern, but this also

has the appearance of tilting forward, because changes in the water

level have to be allowed for. The grade of the Rigi is 1 in 4 for a

large proportion of the way.

DURING the past few years there has been a general speeding up of the

main line railway services of this country, as well as those of the

more important railways of Western Europe and several Overseas and

Colonial lines, especially those of the United States and Canada. The

narrow gauge systems of South Africa, New Zealand, Java and Japan have

also accelerated their important trains.

It is for advertising purposes that certain expresses running long

distances are given names that appeal to the general public. The oldest

is the Flying Scotsman

of the L. & N.E.R., which commenced running in June, 1862. The

down train has left King's Cross ever since, at 10 o'clock every

week-day morning for Grantham, York, Newcastle, Berwick and Edinburgh;

the up train leaves Waverley Station, Edinburgh, at the same time for

King's Cross, making an additional stop at Darlington. Since 1928,

during the summer months, the train runs non-stop in both

directions—the world's record daily non-stop run of 392¾

miles.

The trains are made up of nine 60ft. cars, and a restaurant car set of

three articulated coaches. The order, beginning from the engine, at

King's Cross, being a third-class brake and a first and third composite

for Perth, a third-class car, third-class restaurant-car, kitchen-car,

first-class restaurant-car with cocktail bar, composite and third-class

car, with hairdressing saloon, for Edinburgh, and composite,

third-class and large brake for Aberdeen. Roughly, when loaded, the

weight is 550 tons behind the engine tender.

Other important Anglo-Scottish expresses of the L. & N.E.R.

include the "Highlandman," 7.25 p.m. ex King's Cross to Inverness and

Fort William; the "Aberdonian," 7.40 p.m., and the "Night Scotsman,"

10.25 p.m. trains to Aberdeen.

The "Scarborough Flier" runs non-stop to York during the summer season.

Leaving King's Cross at 11.10 a.m. it covers the 230 miles to

Scarborough in four hours at 57.5 miles an hour.

By way of Leeds and Harrogate the "Queen of Scots" Pullman express

leaves King's Cross at 11.20 a.m. and reaches Glasgow—453½

miles—in

nine hours, and the "West Riding" Pullman, by the same route, departs

from King's Cross at 4.45 p.m., of which one portion arrives at

Newcastle—280.8 miles—in 5 hrs. 38 mins., and the other at

Halifax—202.8 miles—in 4 hrs. 12 mins.

From Liverpool Street the 10 a.m. "Flushing Continental," 7.42 p.m.,

"Esbjerg Continental," 8.15 p.m., "Hook of Holland Continental," and

8.30 p.m. "Antwerp Continental," all connect with the cross-Channel

boat services, and cover the 69 miles between London and Parkeston

Quay, Harwich, at an average speed of over 50 miles an hour, over a

very heavy road. On Sundays the "Clacton Pullman" from Liverpool

Street, at 9.55 a.m., is a popular fast train to the East Coast resort,

the 70¾

miles being covered in 97 minutes. During the summer this

train forms the "Eastern Belle," which is run on week-days to seaside

resorts on the East Coast.

On May 7th, 1903, the G.W.R. ran a 250 ton train hauled by the 4-4-0

engine, City of Bath,

from Plymouth to Paddington, 246¾

miles in

233½

minutes—i.e. 63.3 m.p.h. Just twelve months later the 4-4-0

locomotive, City of

Truro (now preserved at the York Railway Museum),

brought the American Mail over the same route as far as Bristol, and

made a wonderful run. Exeter was passed dead slow in just under 56

minutes from North Road, Plymouth, a distance of 52 miles three chains

over one of the heaviest roads in the country. Then followed a climb to

Whiteball summit at a speed never below 62 m.p.h. Coming down the

Wellington Bank a maximum speed of 102.3 m.p.h. was attained, the

highest speed ever reached in this country by a steam train until the

L. & N .E.R. made its record run at 108 m.p.h. on March 5th

last, with the "Pacific" type locomotive, Papyrus. From

Bristol to

London the train was hauled by the 4-2-2 engine, Duke of Connaught,

with 7ft. 8in. driving wheels, which maintained an average speed of 78

m.p.h. between Wootton Bassett and Westbourne Park—81¾

miles.

These runs were the prelude to the introduction in March, 1932, of the

famous "Cheltenham Flyer," until lately the fastest steam-worked train

in the world, which with unfailing regularity makes the journey from

Swindon to Paddington, six days out of seven, in 65 minutes, a start to

stop speed of 71.4 m.p.h. Frequently the train reaches Paddington in

front of time. On one of its runs the speed of 87½

miles an hour was

maintained for 70 miles of the journey, 28 of which were covered at a

speed of 92.3 m.p.h.

In three months the "Flyer" only lost 7½

minutes on its schedule

timing. During the first ten months of its running the total time lost

was 634 minutes for 306 journeys, an average of 21/10

minutes per

journey. It was on time 172 trips, and 134 times late owing to heavy

traffic and fog. The load is generally six to eight corridor coaches,

with dining car facilities, making a weight of 190 to 250 tons, and

seating 250 to 364 without the dining car (35

seats).

THE "CORNISH RIVIERA LIMITED," G.W.R.—Until the L. & N.E.R.,

in 1928, started the non-stop run of the "Flying Scotsman," the record

for the longest run without halt was held for nearly a quarter of a

century by the "Cornish Riviera Limited," of the G.W.R., the famous

"10.30 Limited," the distance between Paddington and North Road