The book reminds us that citizens in Victorian England lived in a patriarchal society. With two exceptions, the text mentions females rarely and only in minor roles. Of the two ladies found worthy of more detailed consideration, one was a famous actress. Fanny Kemble found herself enthralled both by the primitive steam locomotive on which she was offered a ride and by its driver and designer, George Stephenson. The other lady, of course, was the monarch reigning over the great nation and its empire and whose name became the epithet defining the era. Mr Acworth is happy to enlighten us as to the queen's preferences when travelling on the railway.

Perhaps less expected are alleviations to the Dickensian harshness of life for working men on the Victorian railways. We discover that one of the railway companies manufactures prosthetic limbs to replace those lost in industrial accidents and another has instituted an insurance scheme for its employees which compensates for the weak employer liability legislation then in force.

We note the author's sceptical views of future technology that today we take for granted. By the time 'Railways of England' was published, developments in steam locomotive design had allowed trains to run at continuous speeds of 60 miles per hour, although the author cannot believe that 80 will be routinely exceeded. Likewise he haughtily dismisses the concepts of 'aerial carriages' and the Channel Tunnel. Experimental electrically-powered trains are not much more than 'scientific toys'. It is easy to disparage lack of foresight, but thirty years ago, who would have anticipated the explosion of mobile phones whose number will soon exceed the world's population, not to mention the applications they support? On this subject, we find in this book reference to the new 'telephone' device that will supplement the universal telegraph in facilitating communication. It is worth remembering that the patent for this device was filed by Alexander Graham Bell a mere 14 years before the publication of this book.

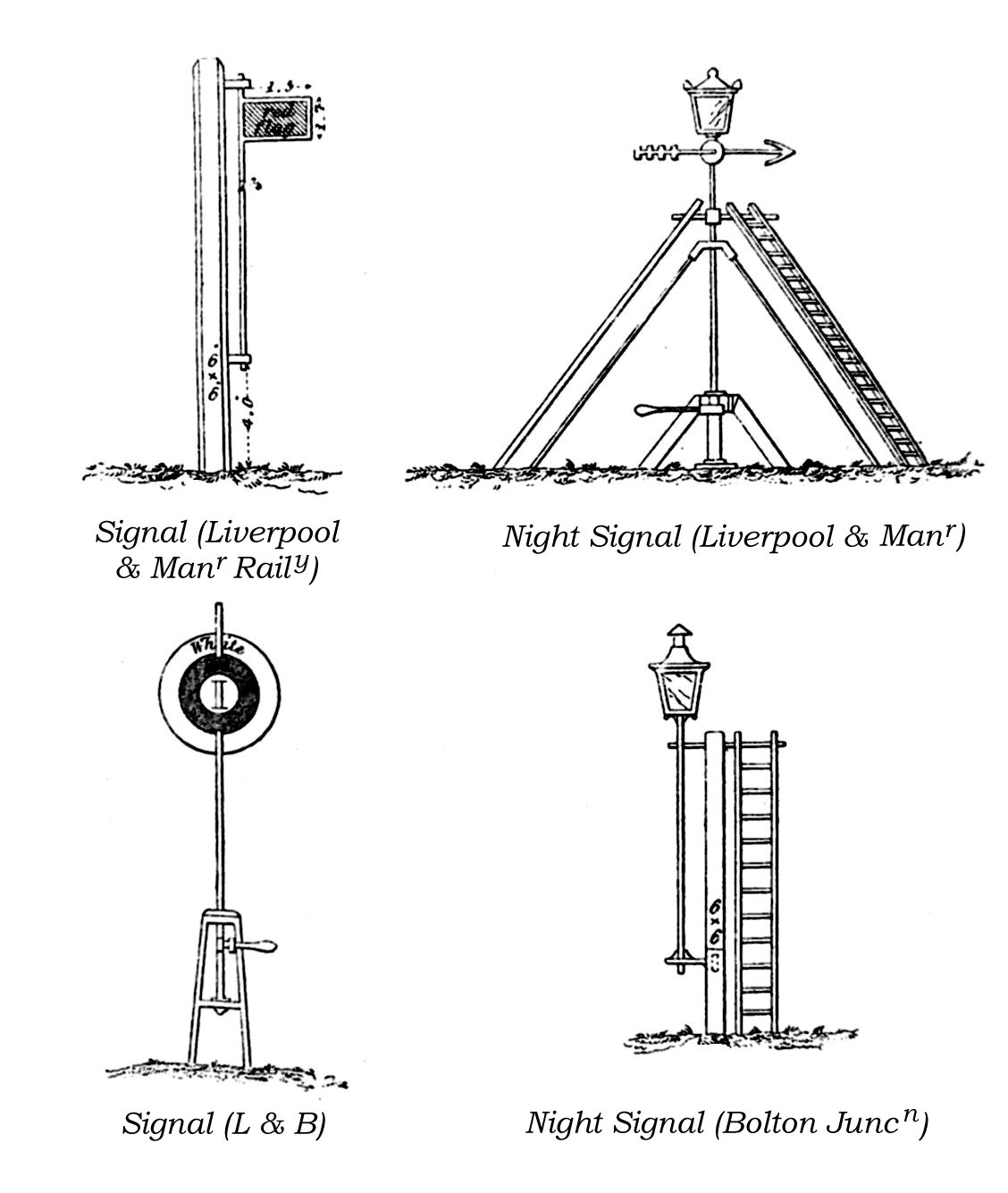

Much of the new technology described by Mr Acworth improved the safety of railway operation. Two examples are the upgrading of braking systems and better signalling. He tells us that continuous brakes are to be found on almost all passenger trains and increasingly on goods trains. We read that the 'block system', protecting trains from collision, relies on mechanical interlocks to prevent signals being cleared when it is unsafe to do so. We also note experiments in alerting drivers to signal aspect in foggy conditions using automatic devices, a forerunner of the Great Western Railway's Automatic Train Control and today's Automatic Train Protection. We read of apparatus which detects the occupancy of railway track by rolling stock and thereby prevents signalmen who control approaches to stations directing trains towards platforms already occupied. The apparatus precludes incorrect signal selection by electrical interlocking. This technology will later be developed into track circuiting protecting running lines. As always, the railway directors have to balance shareholder interest (supremely important in Victorian times) against the cost of safety features and several decades will pass before track circuiting is universally installed on British railways. Likewise, it took an Act of Parliament to force the companies to install automatic braking systems, prompted by the dreadful accident in Armagh which occurred the same year Mr Acworth's book went to press. Eighty lives were lost after inadequate brakes failed to stop a runaway train.

In the matter of carriage lighting the author notes approvingly that old-fashioned oil-lamp lights are being superseded by gas-burning systems, and experimentally on some lines, electrical systems. The potential dangers of gas lighting apparatus in wooden bodied railway carriages are not mentioned. Sadly, a quarter of a century later, in Britain's worst railway disaster, wooden carriages shattered in a three-train collision will be set on fire by ruptured gas-lighting cylinders, ignited by red-hot coals spilling from locomotives. More than two hundred soldiers will lose their lives at Quintinshill after errors by signalmen. It is worth noting that this terrible accident could never have occurred had track circuiting been installed on the section of track controlled by the adjacent signal box.

A development mentioned in Mr Acworth's text is the imminent demise of Brunel's broad gauge on the Great Western Railway at the end of the Battle of the Gauges which started five decades earlier. We also find precursors of future problems such as overcrowded trains and stations in the London area and village shopkeepers deploring the new trend of their customers preferring to travel by train to the city to make their purchases rather than patronising local establishments. In the modern version of course the car has taken the place of the train and the shopping mall that of the city.

Another glimpse of the future is to be found in the description of a 'gas engine', a precursor of the internal combustion engine found in nearly all of today's non-railway ground transport vehicles. The engine in Mr Acworth's book (literally powered by gas) is a humble device for driving a dynamo which charges the accumulators in coaches featuring electric lighting. The shape of things to come is also hinted at in the form of trials of liquid fuel for locomotives, albeit as a substitute for coal in steam engines.

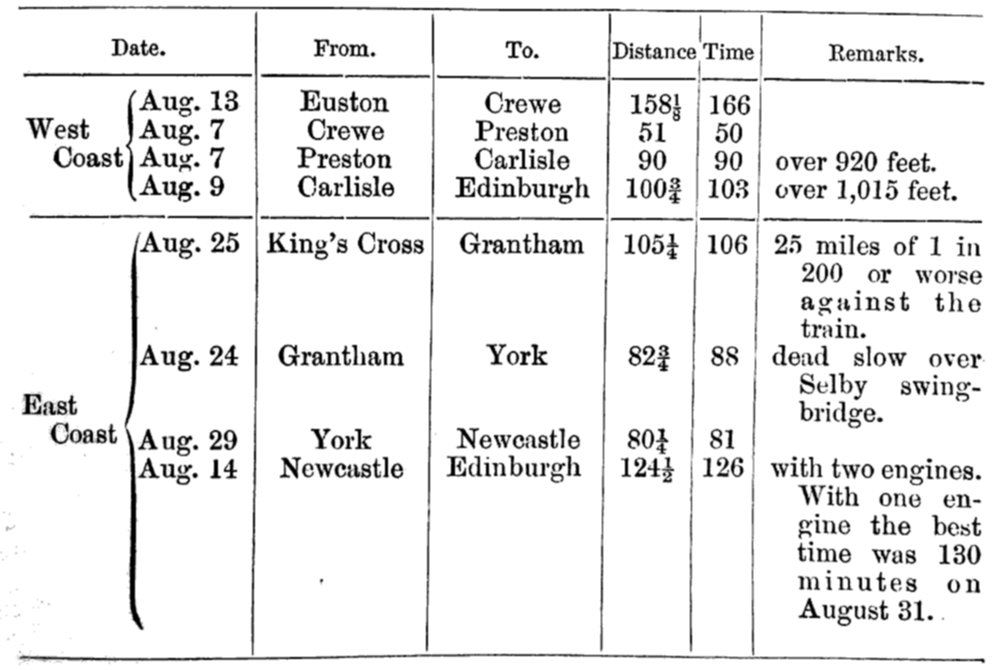

In some regards Mr Acworth exemplifies the typical Victorian Englishman, confident that he is a citizen of the greatest nation on earth. He takes pride in the superiority of English railways in speed, comfort and economy compared to Continental and American railways. He warns us of the folly of state control and laments the 'red tape' that hinders private enterprise. We are informed that the Great Northern runs the fastest trains in the world. At the time the book was written the railway companies were unofficially competing in the 'Race to the North' between London and Scottish cities. In today's Britain, of course, high speed trains are notable by their absence. Whether this situation should be rectified is still stirring controversy.

Mr Acworth does not shy away from finding fault with foreigners. The weight of German passengers triggers uncomplimentary reference and the honesty of Americans is unfavourably compared to that of the English. The author also quotes another writer who mentions the 'heartfelt inertia' of the French porters at Calais.

A thread running through the book deals with the financial aspects of railway operation, including construction and running costs, passenger fares, rates for carriage of goods, wages for workers and shareholder dividends. The British pound (Latin libra, worth roughly £100 in today's money) was divided into twenty shillings (Latin solidus), each of which was in turn divided into twelve pence (Latin dinarius), giving rise to the abbreviation £ s d for the nation's currency. This antiquated currency system survived until decimalisation in 1971.

There are one or two curiosities to divert us as we make our way through this treatise on Victorian railways. Commenting on the design of locomotives, Mr Acworth tells us: 'modern practice, however, has shown that engines with a high centre of gravity not only run more smoothly and are less hard upon the permanent way, but actually are safer in running round sharp curves at a high rate of speed.' This judgement seems to deny the laws of physics and we cannot know the derivation of the author's belief. In an opinion diametrically opposed to modern concern about burgeoning levels of carbon dioxide (which when hydrated produces carbonic acid) in our atmosphere, a railway engineer quoted by Mr Acworth says: 'engines ought to employ their power in impregnating the earth with carbonic acid and other gases, so that vegetation may be forced forward despite all the present ordinary vicissitudes of the weather, and corn be made to grow at railway speed.'

More light-heartedly we find—several decades before the Reverend W Awdry invented Thomas the Tank Engine to amuse his son—a cartoon satirising the poor performance of the Eastern Counties Railway, in which a locomotive (hauled by a donkey) features an unhappy face drawn on its smokebox. The caption to the cartoon derives from the famous painting 'Rain, Steam and Speed' by William Turner, an evocative depiction of an early Great Western express. Below our grim-faced engine in this book we find: 'Rein, Steam and Speed.' Did the Good Reverend find his inspiration in Mr Acworth's book?

The author's writing style looks somewhat quaint to modern readers but is probably typical of the era. Constructions are sometimes convoluted, frequently encumbered by multiple qualifying clauses. Sometimes a sentence must be read more than once to extract its meaning. This Victorian English style is closer to its Germanic origins than today's language, which explains the plethora of commas peppering the text, the greater prevalence of subjunctive verbs and constructions such as 'five-and-twenty' rather than 'twenty-five'. We also find a fair sprinkling of Latin words and phrases, as would be expected from the pen of an educated man. Some words look strange to modern eyes, such as 'se'nnight' (seven nights, meaning a week) and 'twelvemonth' (year) and some are spelled differently, such as 'tire' for 'tyre', 'under weigh' for 'under way' and the names of foreign cities. The meaning of some words has changed during the intervening years. The 'casino' mentioned by the author refers to a public dance hall rather than a gaming establishment. And when we read of 'vans' and 'lorries' we must remember that these are horse-drawn vehicles in Victorian Britain. Mr Acworth frequently uses the word 'road' when talking about railway lines or routes, a practice still common in the United States and indeed amongst railway operating personnel in modern Britain.

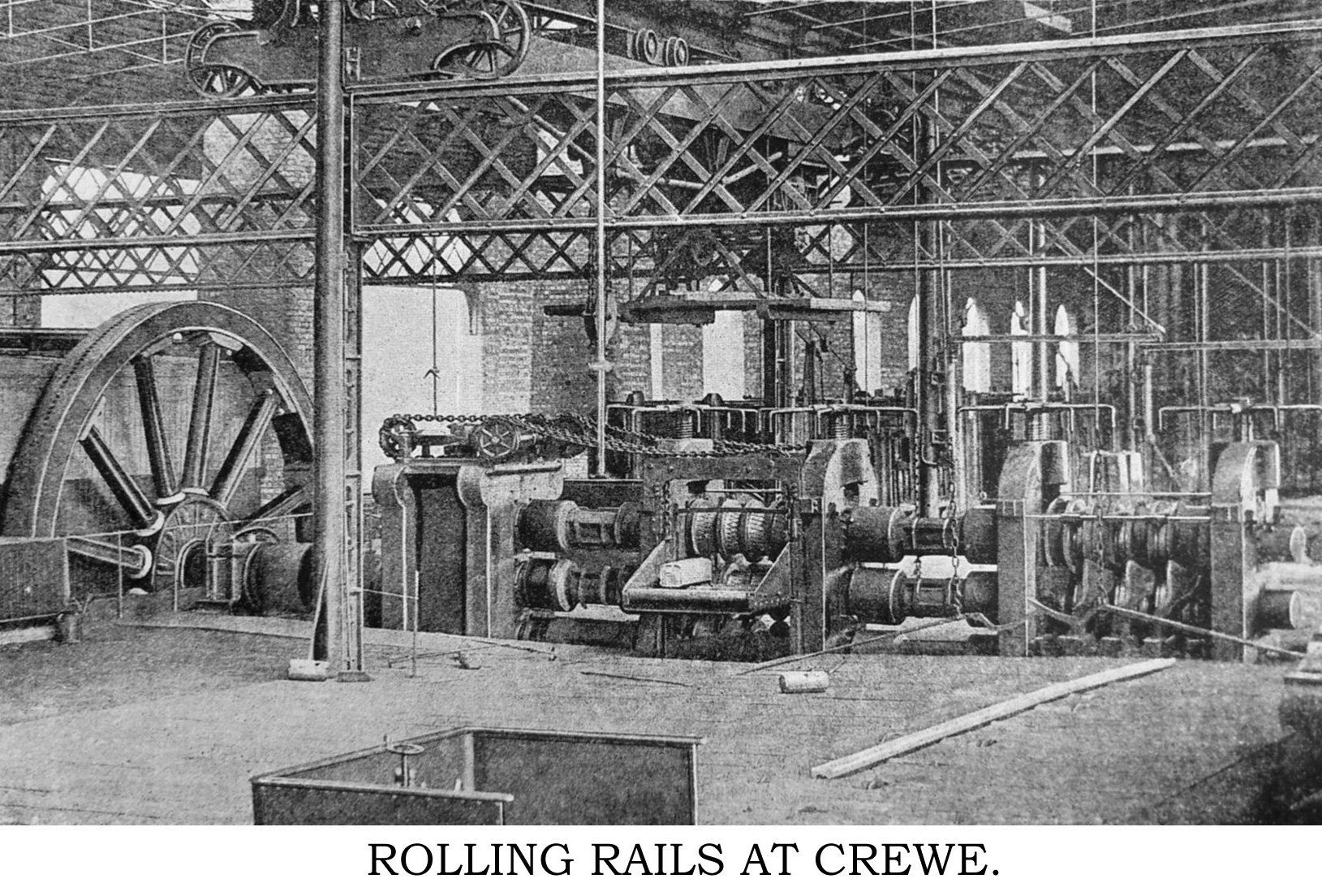

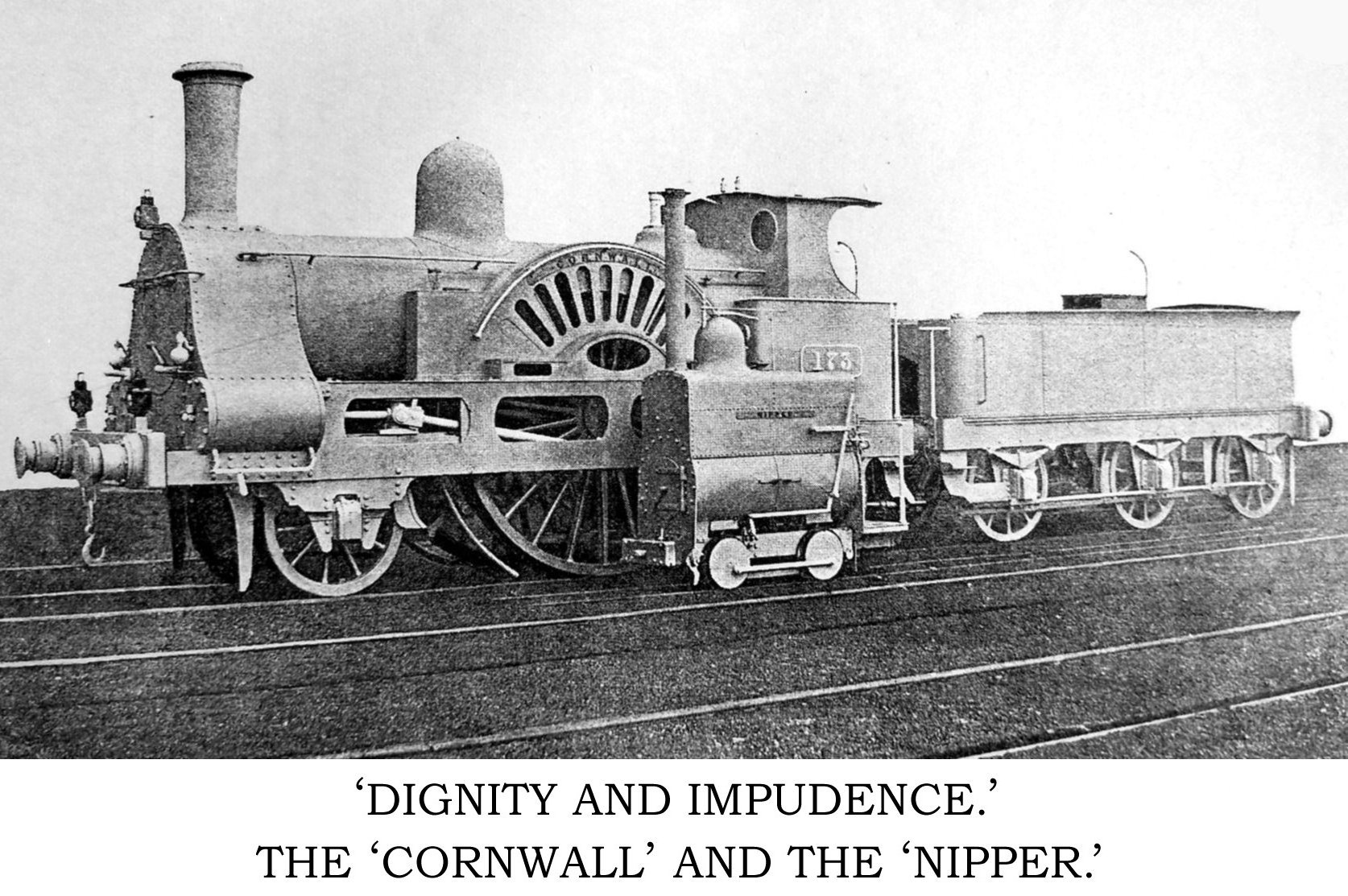

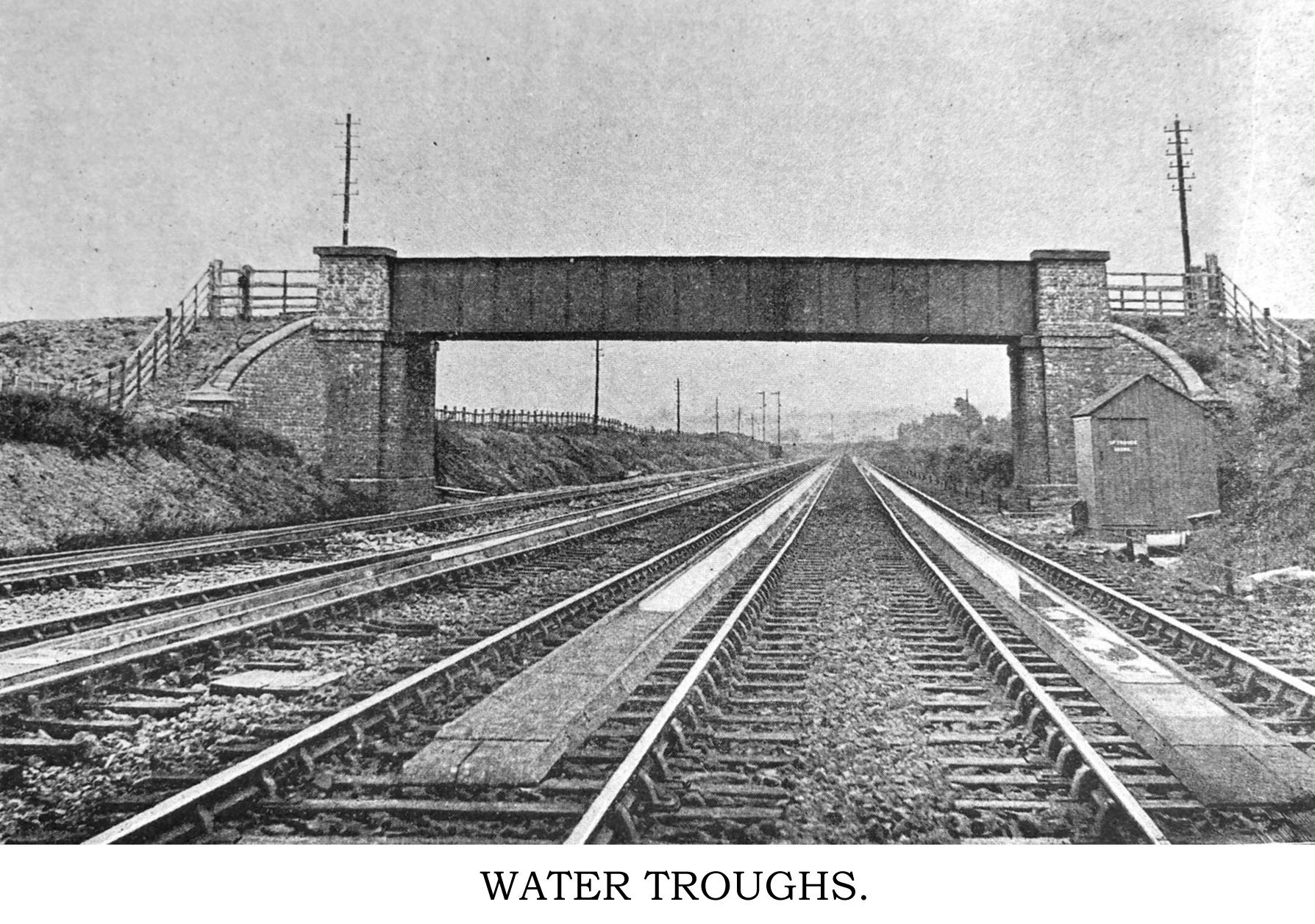

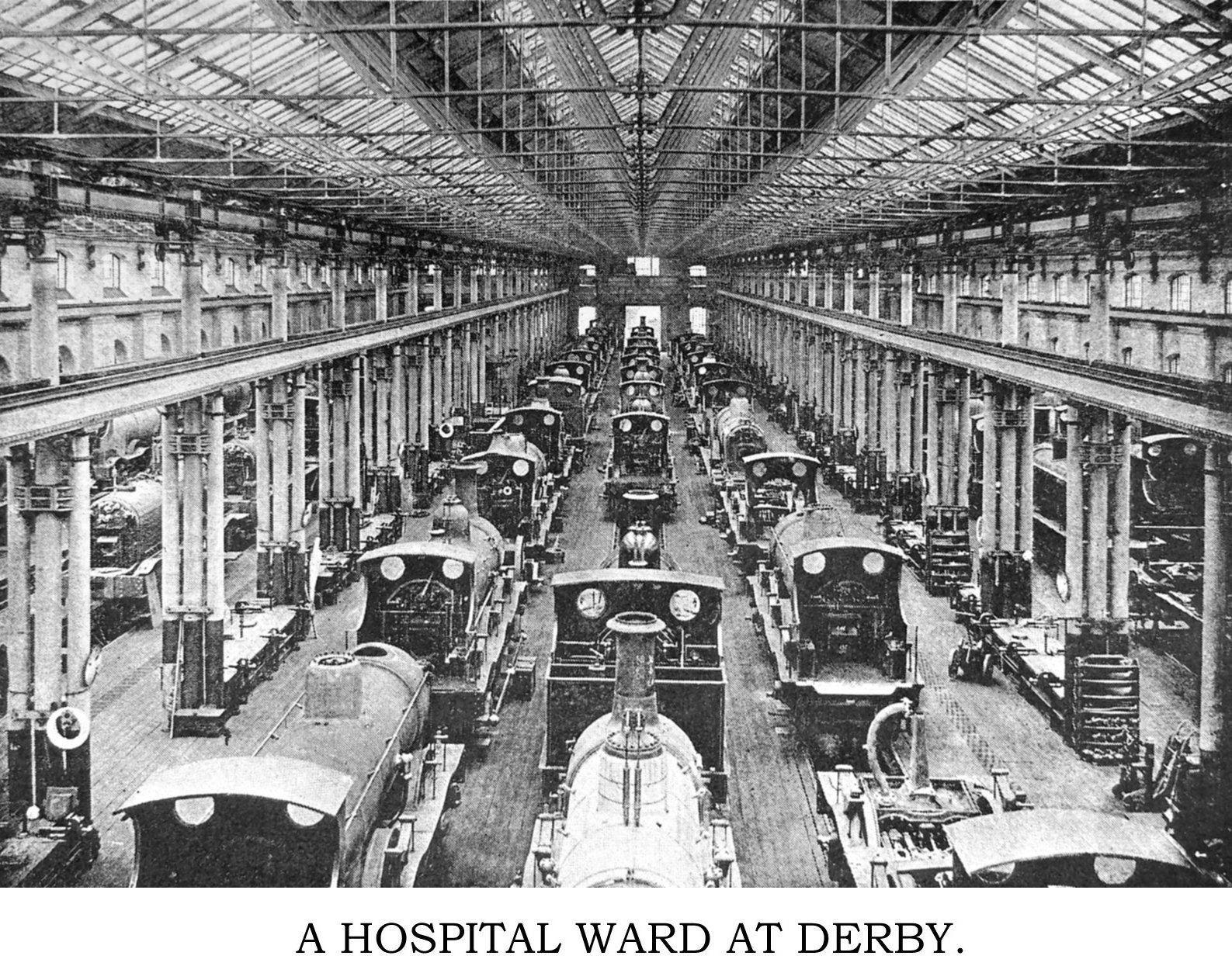

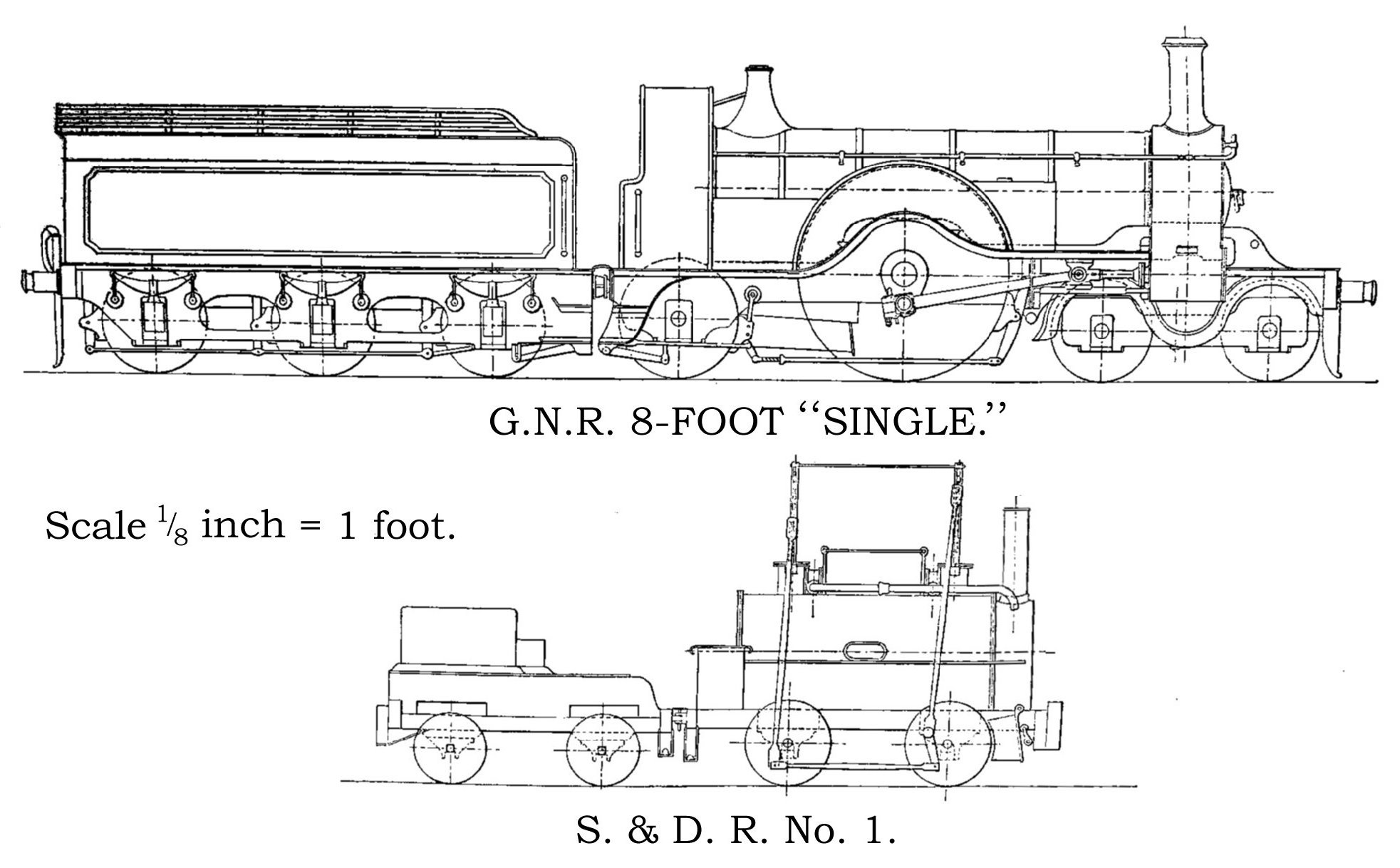

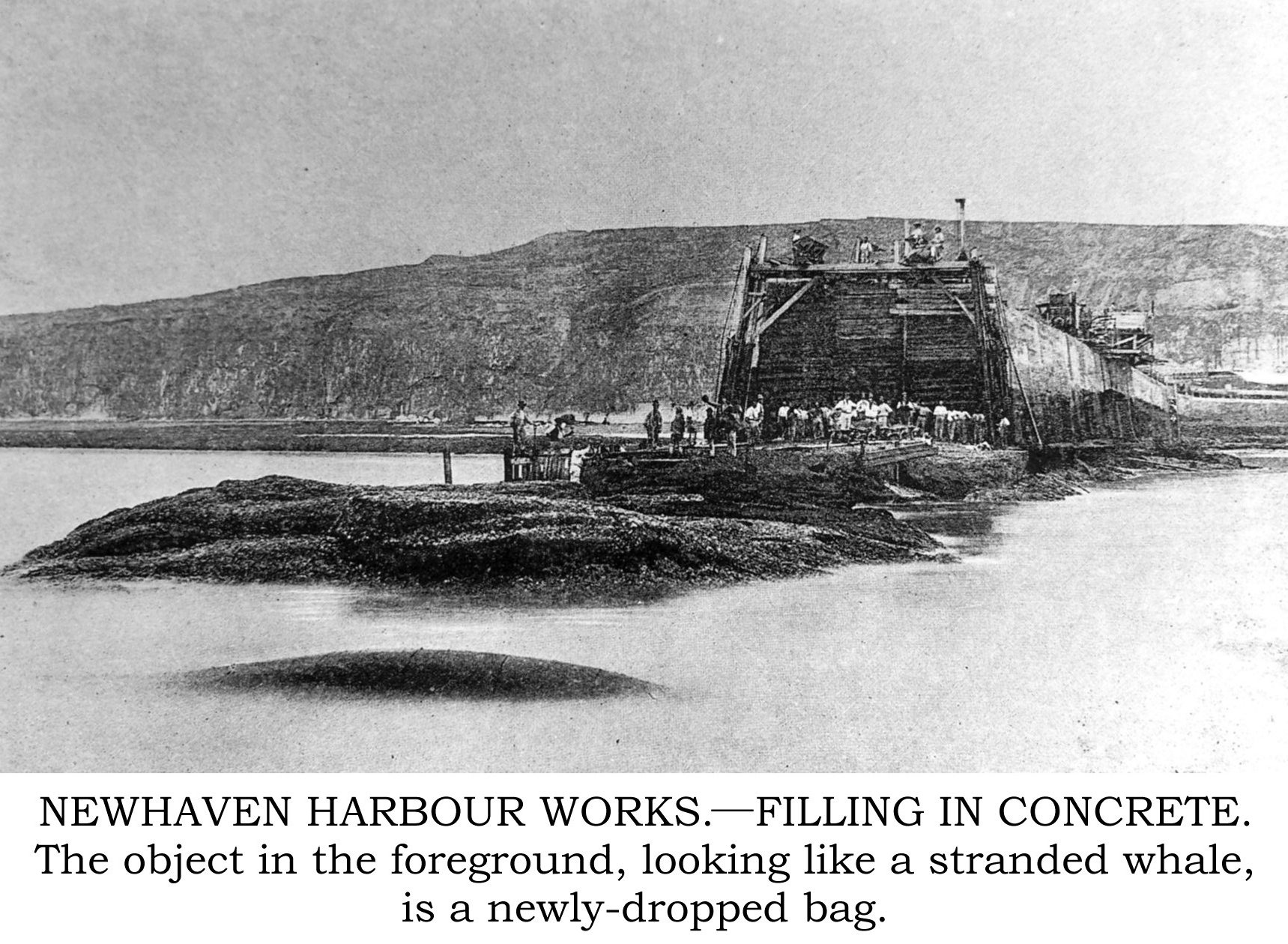

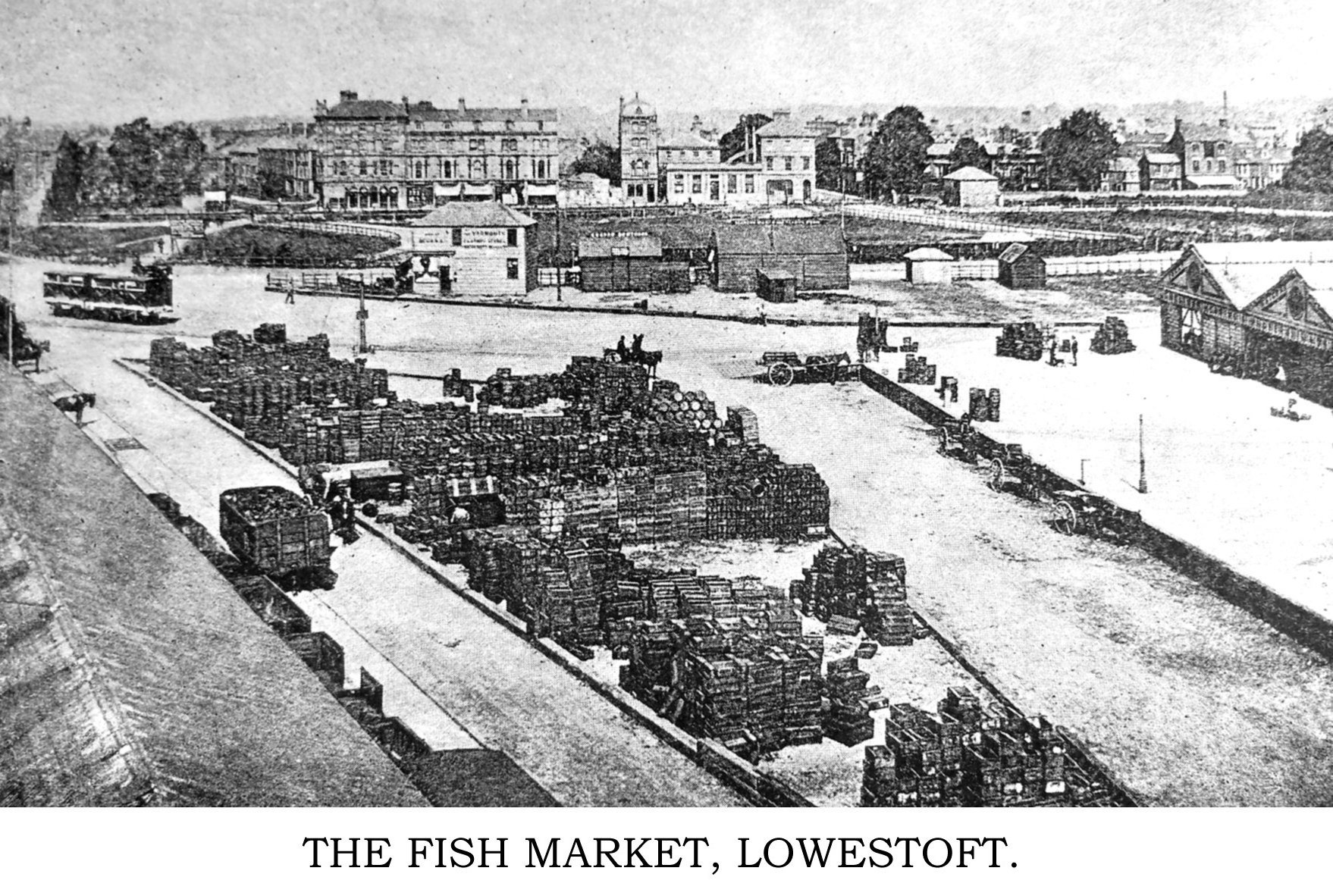

In formatting this book for republication I have corrected obvious typographical errors and stylistic inconsistencies where detected but otherwise have stuck as closely as possible to Mr Acworth's original text. I have presented footnotes in parentheses and in italic script and have positioned them as closely as possible to the text to which they refer. The quality of the photos illustrating the book is poor by modern standards but it must be remembered that in the 1880s the art of photography (and of processing photos for inclusion in books), while no longer an infant, was still in its formative years. A higher quality photo, featuring a Great Northern Stirling 8-foot Single locomotive (courtesy Tony Hisgett) follows these notes. This machine represents the pinnacle of British steam traction in that decade.

I hope readers of this edition of 'Railways of England' are satisfied with the results.

I have published before now not a few criticisms (which were meant to be scathing) on English Railways anonymously. I find myself using, under my own name, the language of almost unvarying panegyric. This is partly to be explained by the plan of the book, which professes to set before the reader those points on each line which best merit description—its excellences, therefore, rather than its defects. Much more, however, is it due to a change of opinion in the writer. The more I have seen of railway management—and in the course of the last two years I have seen a good deal—the more I have realised the difficulty of the problem set before the railway authorities for solution, and the more I have appreciated the success with which, on the whole, they have solved it. I have found in so many cases that a satisfactory reply existed to my former criticisms, that I have perhaps assumed that such an answer would be forthcoming in all; and, if I have taken up too much the position of an apologist, where I should have been content to be merely an observer, let me plead as my excuse that I am only displaying the traditional zeal of the new-made convert.

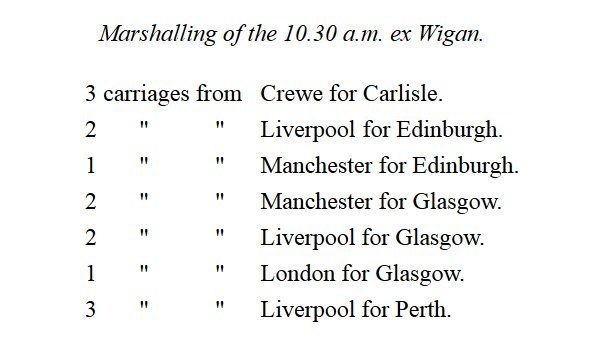

Further, it seems only right to disclaim any idea that what I have written is a complete and symmetrical gazetteer of the whole English railway world. I have only professed to deal with railways terminating in the Metropolis. The mention of the rest is only incidental and complementary to these. Again, "Never refuse traffic" is the motto of every railway manager in the country, and there is not a line but carries passengers, and goods, and minerals of all classes. I have, however, as a rule, dealt with each class of traffic but once, and described it under the railway in whose business it formed the most prominent feature. Without this explanation it might seem invidious—to take instances from the first two lines mentioned in the book—to ignore the fact that the Midland carries many millions of letters, and that the North Western carries many million tons of coal.

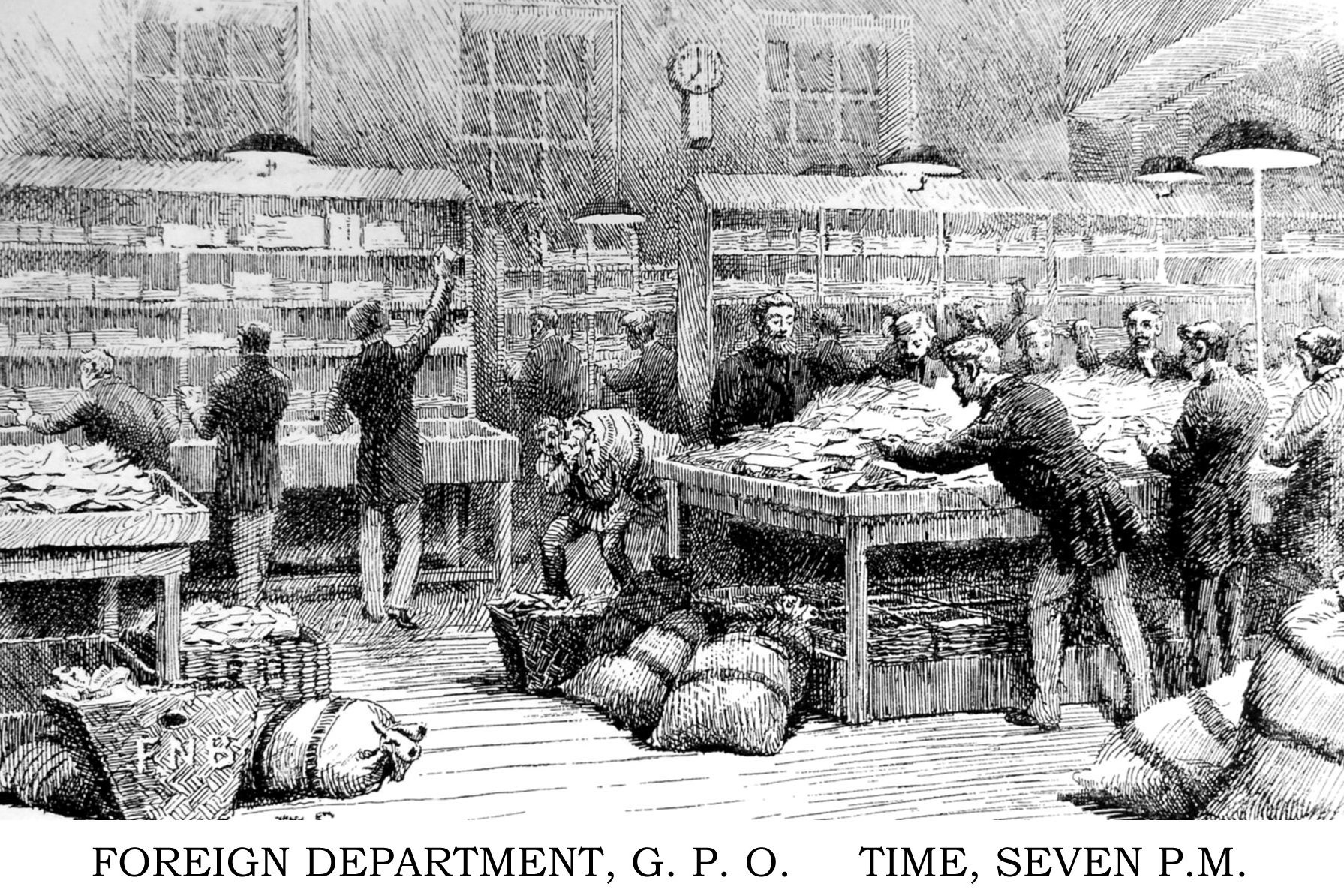

I have also to express my much more than merely conventional gratitude to the officials and servants of the various companies, without whose assistance—as must indeed be obvious on every page—this book could never have been written at all. To mention each of them by name is impossible; to do so would be to run through the list of the heads of departments of almost all the great lines in the country. And even then I should have neglected to thank innumerable inspectors, signalmen, and engine-drivers, and others, who have contributed not a little to my education and instruction. From the universal readiness to permit an outsider to go where he liked, and see what he liked, and to get answers to any questions he chose to put, it would appear that English railway managers can have but few skeletons in their cupboards. I have also to thank the authorities of the Post Office for the facilities which they have in all cases courteously placed at my disposal.

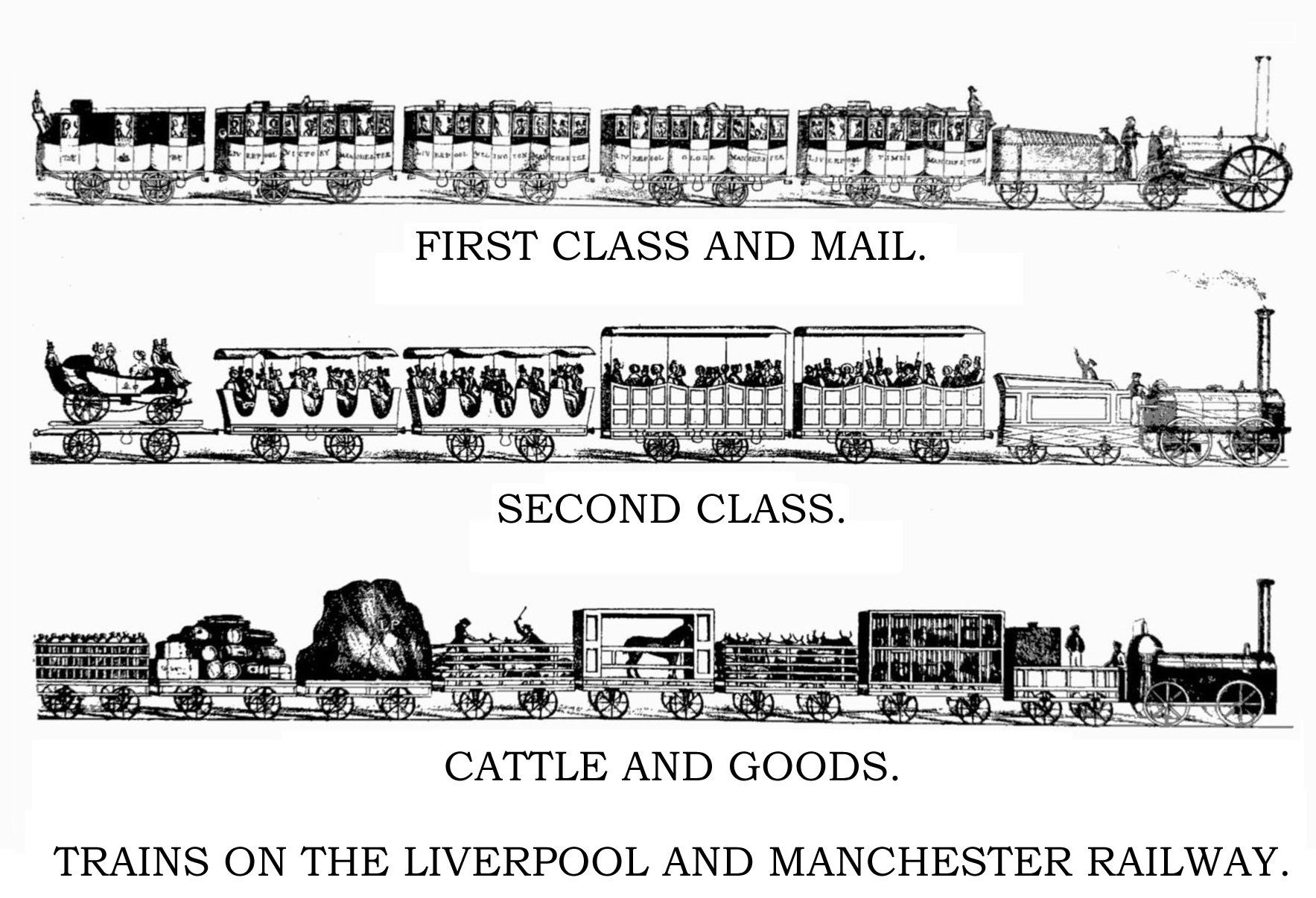

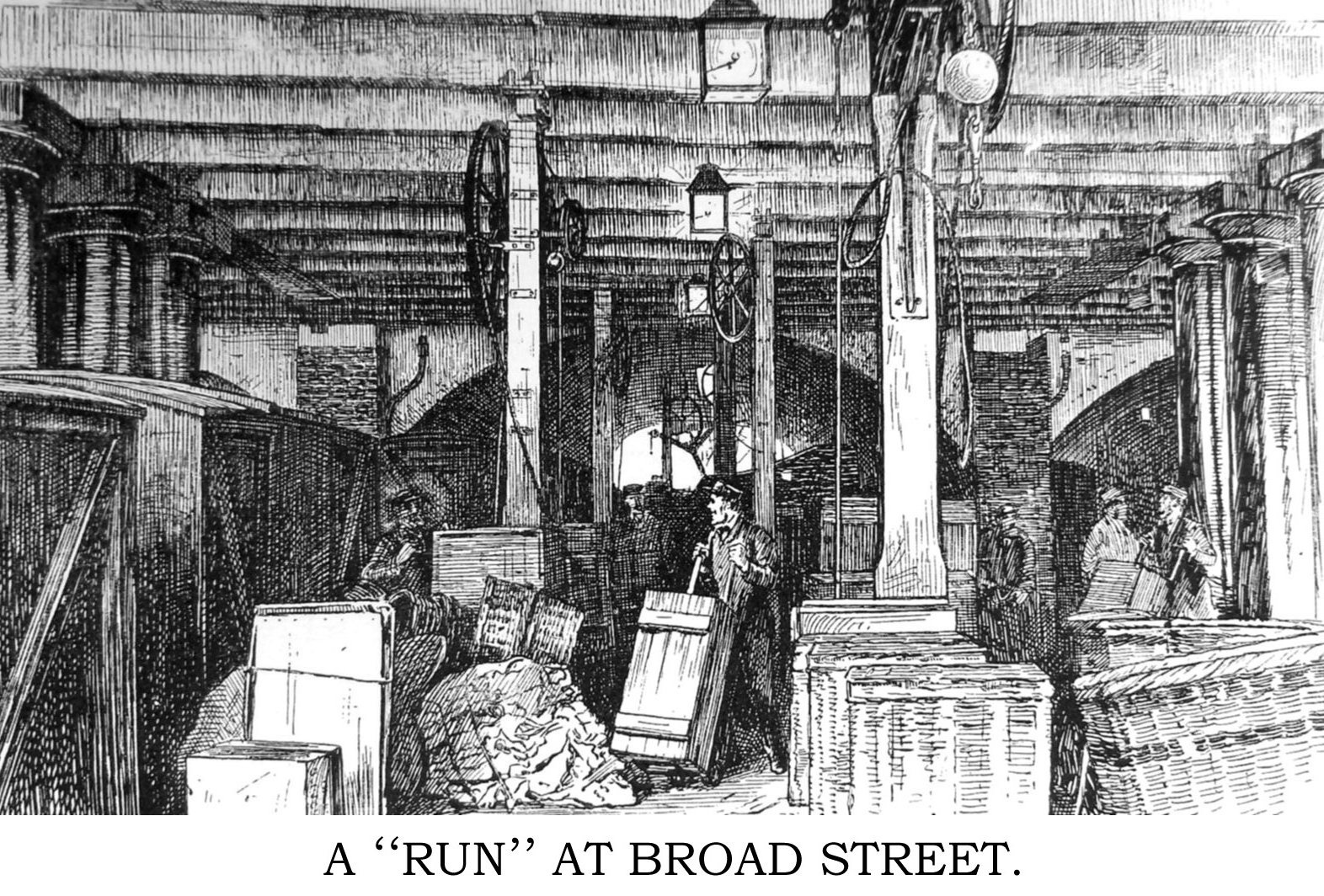

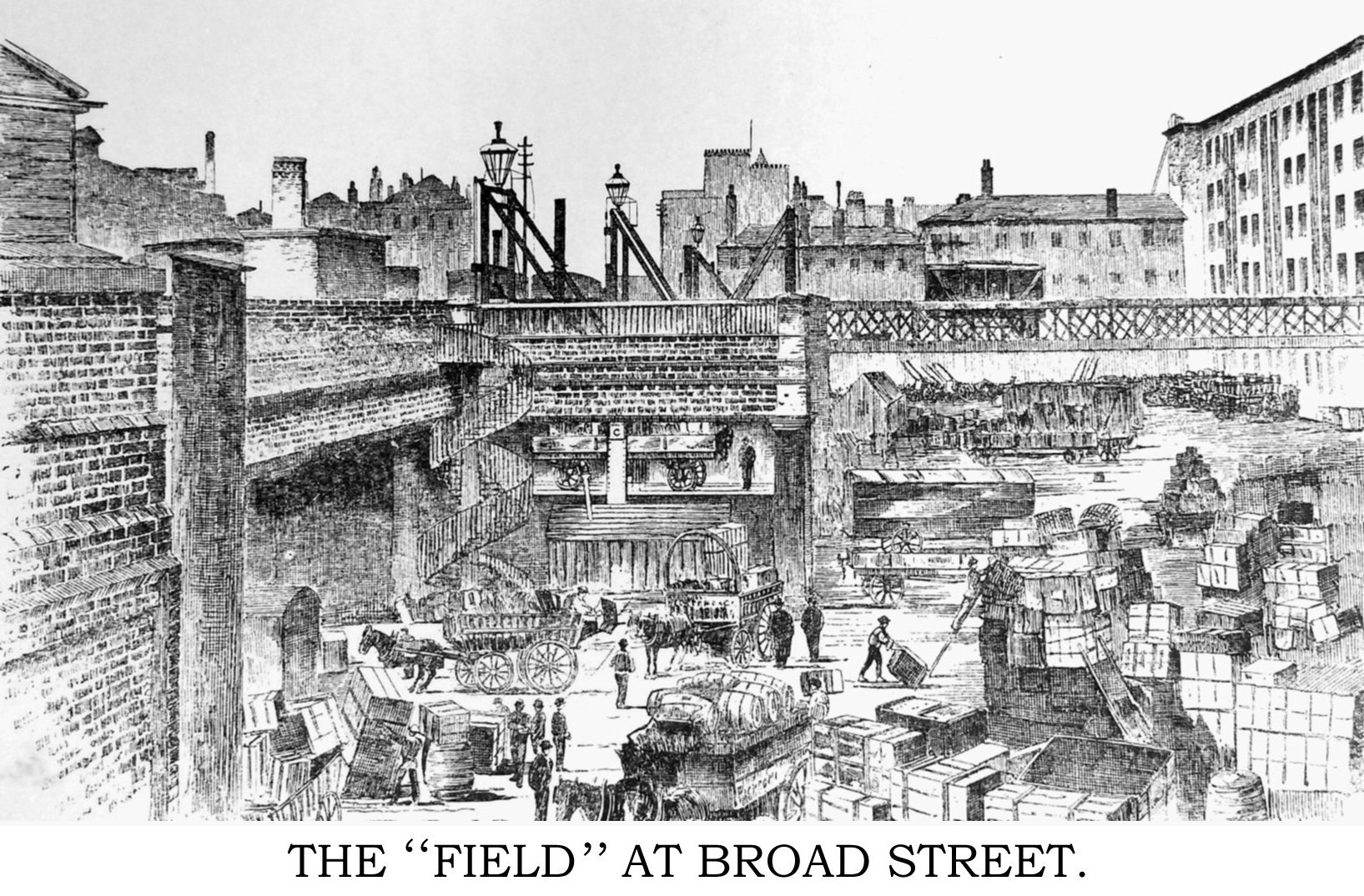

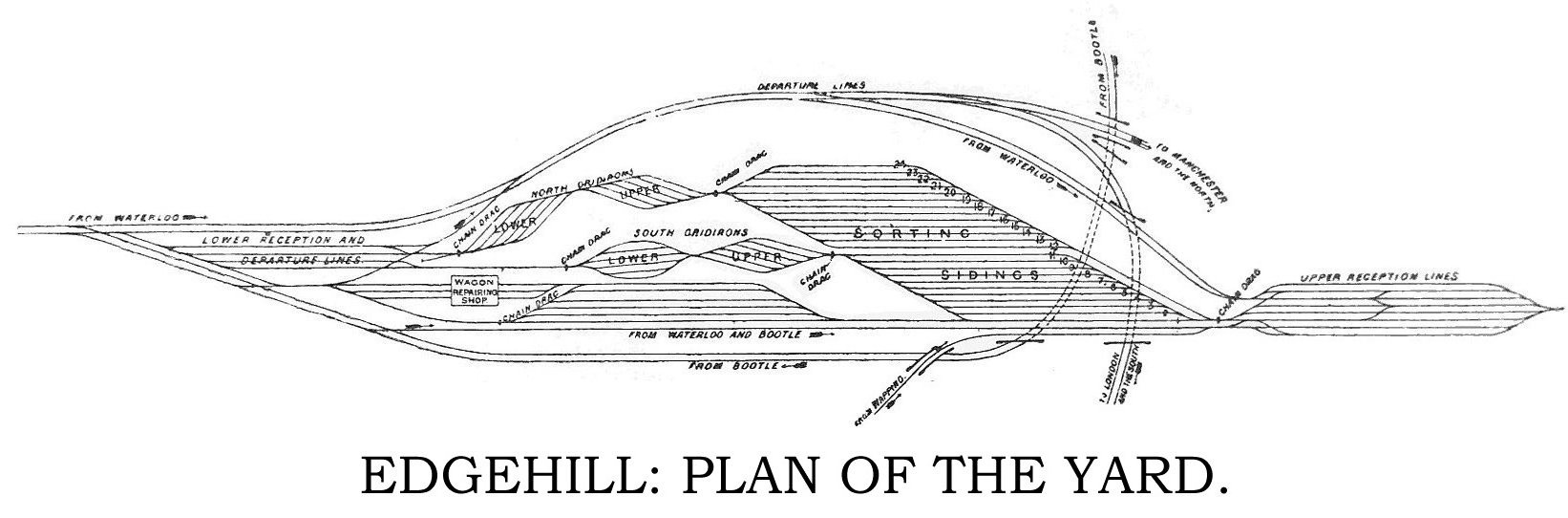

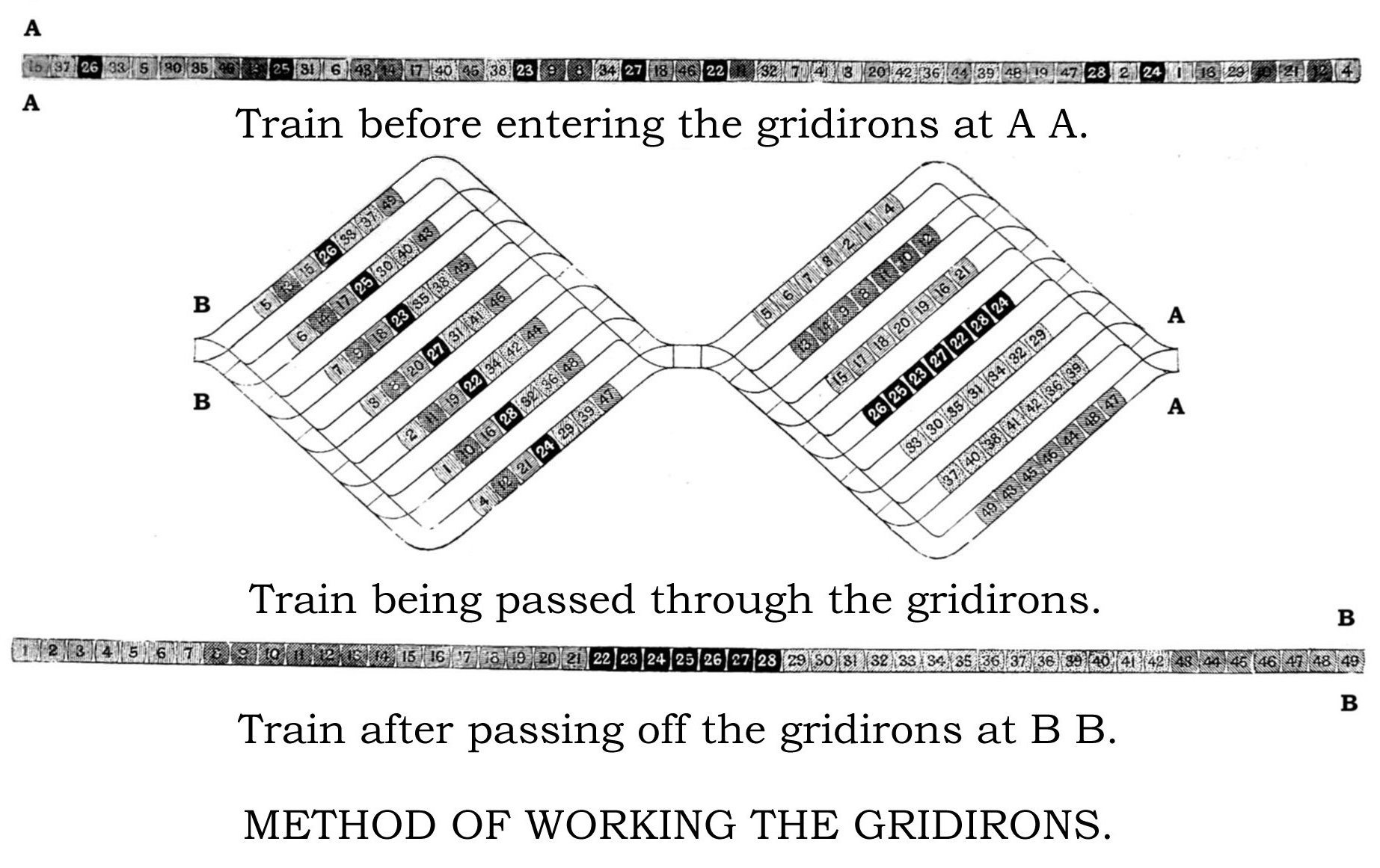

Finally, I must make a special acknowledgment of the kindness to which I am indebted for the various illustrations. In particular I have to thank Mr. Findlay and Mr. Footner for leave to reproduce their diagrams of Edge Hill, Mr. Cameron Swan for a photograph of the apparatus of the Travelling Post Office in action, Mr. Fay for the picture of Waterloo in 1848 (as well as for the information in his book on the South Western line), Mr. Arthur Guest for the drawing of the Liverpool and Manchester Company's trains, the Editor of the Railway News for the illustration of the patent "feather-bed train," Messrs. Ransome and Rapier for the illustration of the hydraulic buffers at St. Paul's Station, and Mr. W. C. Boyd for the caricature referring to the old Eastern Counties. The rest of the modern illustrations I owe in almost every case to the courtesy of the officials of the different lines concerned.

January, 1889.

All the world knows that the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was opened in 1830, and that the Railway Mania occurred in 1846. The year 1843 marks the period of transition between these two points, and enables us to sketch the English railway system in a condition more nearly approaching a stable equilibrium than it has ever attained either before or since. A long and severe depression of trade, consequent on a series of bad harvests that culminated in the Irish potato famine and the Repeal of the Corn Laws, had brought railway building almost to a standstill, and had rendered it well-nigh impossible for projectors to obtain the money for new schemes.

But the main foundations of our railway system were already laid, and with the exception of the Great Northern, and of course of the Chatham and Dover, all the great companies were already in existence, or at least in embryo. The London and Birmingham had not yet united with the Grand Junction, the Manchester and Birmingham, and the Liverpool and Manchester to form the North Western, but passengers could travel from Euston, viâ Birmingham and Crewe, not only to Liverpool and Manchester, but to Chester, Lancaster, and Leeds as well. To the north-east they could travel as far as Hull and Darlington, though the Hull and Selby, the Great North of England with its 44¼ miles of line, the Clarence, the Brandling Junction, and half a dozen more, not forgetting the Stockton and Darlington, squabbled and fought over different corners of the territory where now the North Eastern reigns in undisputed sovereignty. The North Midland, the Birmingham and Derby, and the Midland Counties were on the eve of amalgamation into the Midland Railway,—the "Great Midland," as it was considered that a company controlling no less than 130 miles of line had a right to be called. In the eastern counties too the first of the coalitions that has finally given us the Great Eastern was just taking shape. South of the Thames, the South Eastern was open to Folkestone; the Brighton line was finished, as was the South Western to Southampton and Gosport. The Great Western was running to Bristol and to Cheltenham, while the extension to Exeter was open beyond Taunton, and was fast approaching completion. There were also a good many lines scattered about England, from Hayle, Bodmin, and the Taff Vale, to that which was perhaps the most important of all, the Newcastle and Carlisle, but having no communication with the main railway system.

In all, some 1800 miles were open for traffic, and no great amount beyond this was under construction. The 1650 miles open at the end of 1841 had only been increased by 179 at the end of 1843. This latter year, however, saw the Parliamentary notices lodged for the Chester and Holyhead. In Ireland there was a railway from Dublin to Kingstown, and also a few miles in Ulster. In Scotland there were some local lines near Dundee, and direct communication was also open from Edinburgh to Glasgow, and on to Ayr and Greenock. But nine-tenths of the mileage was in England. The amount of capital authorised was about £70,000,000, and of this nearly £60,000,000 had already been spent. About 300,000 passengers were carried every week, and the total weekly receipts from all sources were somewhat more than £100,000. For purposes of rough comparison, it may just be mentioned that to-day there are nearly 20,000 miles of line in Great Britain, about seven-tenths of them in England and Wales, that the paid-up capital exceeds £800,000,000, that the annual receipts are more to-day than all the capital in 1843, and that the number of passengers has increased more than forty-fold.

A General Railway and Steam Navigation Guide, bearing already the familiar name of "Bradshaw," though not yet clad in the familiar yellow garb, had been for some time in existence, and had just begun to appear regularly on the first of each month; but, in spite of ample margins and wide-spaced columns, it was necessary to insert much extraneous matter relative to railways under construction and the price of shares in order to eke out the thirty-two pages of which the slim pamphlet was composed. Then, as now, its price was sixpence.

Competent observers were, however, convinced that all the lines it would pay to construct were already made. For instance, it was gravely argued that the Lancaster and Carlisle (a line that in fact paid enormous dividends for years before it was absorbed into the North Western) would "prove a most disastrous speculation." It was evident, said the wiseacres, that it could never have any goods traffic; and as for passengers, "unless the crows were to contract with the railway people to be conveyed at low fares," where could they be expected to come from? The through traffic could be conveyed almost as expeditiously and far more cheaply in the "splendid steamships which run to Liverpool in sixteen or seventeen hours from Greenock." As for the rival East Coast scheme, "this most barren of all projects, the desert line by Berwick," was even more fiercely assailed. "A line of railway by the [East] coast," writes one gentleman, "seems almost ludicrous, and one cannot conceive for what other reason it can have been thought of, except that the passengers by the railway, if any, might have the amusement of looking at the steamers on the sea, and reciprocally the passengers by sea might see the railway carriages."

"The improvements that are constantly taking place in marine engines and steam vessels," writes another correspondent, "are so great that there cannot be a doubt but they will soon attain an equal rate of speed to the present railway locomotives." For all that, the East Coast route was strongly advocated, and an influential deputation, headed by Hudson and Robert Stephenson, had an interview with Sir Robert Peel at the Treasury to solicit Government assistance to the project. The construction of the High Level Bridge at Newcastle, as a single line to be worked by horses, was under consideration. Speaking of the proposed Caledonian line from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Carlisle, the Railway Times writes in January, 1843, that "if in any way the present attempt should be rendered nugatory, the next ten years will not see the commencement of a line to Scotland by the West Coast." (The Caledonian line was projected and surveyed by Mr. Locke as early as 1836, but the name was not invented till 1844, on the eve of the great Parliamentary contest of the following year. The Annandale, the Clydesdale, the Lanarkshire, the Evan Water, the Beattock, were some of the names by which the original scheme was known.) "Long before that time the route viâ the East Coast will be completed, if its promoters proceed with the same spirit as heretofore; and, although ultimately there may be and must be two distinct lines between the capitals of England and the North, it is almost certain that, unless some great improvement takes place in the making and working of railways, the present generation will not witness the execution of both." The prophet's vision was so far correct that the East Coast was open first, but it was only the difference between July, 1847, and February, 1848.

It was urged, however, by competent authorities that the completion of "an undertaking of so much national importance" might be antedated, if the proposals of "Wm. F. Cooke, Esq., the ingenious originator and successful introducer of the system of electrical telegraphing," were adopted. That gentleman considered that "the whole present system of double way, time-tables, and signals, is a vain attempt to attain, indirectly and very imperfectly, at any cost, that safety from collisions which is perfectly and cheaply conferred by the electric telegraph." He urged the adoption of what was sometimes known as the "reciprocating" system, or what we should call single-line working. "It is not necessary that a railway should be of one construction throughout a widely varied country. A mixed line would convey any quantity of traffic, and might at the same time admit of an enormous reduction of prime cost. On the principle on which the width of a canal is diminished at a lock or an aqueduct, the tunnels, viaducts, high embankments, and deep cuttings of a railway might be made on the scale of a single way, expanding into the double way in a more open and level country. Let this principle be carried a little farther by submitting to a reduced speed at a few sharp curves and steep gradients, introduced to accommodate a line to the natural defiles of a mountainous district, and a million might be saved on 10 or 15 miles of heavy works in a line of 150 miles in length, which for the remainder of its course would be constructed with a double way. This combination of the single and double way would be peculiarly appropriate to the case of a Scottish junction line to unite the eastern or western capital of Scotland with our English railways, a line which must on either coast include several heavy works of so expensive a nature as at present to render it very doubtful that this great national union could prove a profitable undertaking. But let the expense of these heavy works be reduced nearly one-half by contracting their scale, and the main obstacle to the undertaking is removed."

We must have another quotation from Mr. Cooke. He was, be it remembered, not only a distinguished electrical engineer, but also practically concerned in the working of railways. And this is the direction in which Mr. Cooke expected that railways would develop. One great advantage of adopting his system would, he declares, "consist in the more perfect adaptation of a railway to the wants of the country through which it passes. Passengers might be taken up, as on the Liverpool and Manchester line, at very short distances; and to save expensive stations, and prevent impatience when a train is late, a bell might be rung for some time before the arrival of a train, to publish to the neighbourhood its gradual approach. Passengers might be collected in horse carriages; and agricultural produce might be carried in wagons along the railway, in the intervals between the trains. Short branches might be worked entirely by horses, in correspondence with the trains upon the main line. Such minor sources of traffic would deserve the attention of a railway, in proportion as cheapness of construction enabled smaller returns to realise the same proportional dividend. Numerous little rills and streamlets would swell the tide of traffic; and the roadside population would at length participate in the convenience of the vast works which have deprived them of their local conveyances; in short, many lines of railway might become what all were once intended to be, highway-roads open to the use of the public." Mr. Cooke's imagination, however, could not soar to the heights attained by one ingenious person who looked forward to railways benefiting the agricultural interest in a very different manner. Engines ought, he considered, "to employ their superfluous power in impregnating the earth with carbonic acid and other gases, so that vegetation may be forced forward despite all the present ordinary vicissitudes of the weather, and corn be made to grow at railway speed."

Not only was railway construction pretty much at a standstill, but there were those who were persuaded that, though railway building was a very good thing in its way, it was a thing that already had been very much overdone. Here is what the Athenæum wrote on the subject in May, 1843:—"With a view to the future, let us glance at the facts as they now stare us in the face; in the first place, look at the vicinity of London. Two railways—the Northern and Eastern, and the Eastern Counties, to Cambridge and to Colchester—are carried into the same district; both are unsuccessful—one might have served all the purposes of both, and perhaps neither is the line that should have been adopted. At all events, one of the two is useless—total loss, say £1,000,000. Next, to the westward, it is plain that one line should have served for the Great Western and the South Western, as far as Basingstoke and Reading—total loss, say £1,000,000. When going north, we have two lines parallel with each other, the Birmingham and Derby, and the Midland Counties, the latter of which should never have existed—total loss, £1,000,000. Then Chester and Crewe, Manchester and Crewe, and Newton and Crewe, and Chester and Birkenhead, three of them unprofitable, a total loss (without any advantage) amounting to £1,500,000. That the Manchester and Preston, and the Newton and Preston, and the Leigh and Bolton should co-exist in the same district, is a further absurdity, costing at least an unnecessary £500,000. No one acquainted with the country can for a moment admit that both the Manchester and Leeds, and Manchester and Sheffield should have been made as separate railways, at a loss of £1,500,000. Thus might good legislation have rendered to the country two essential services. The whole traffic at present existing might have been concentrated on the remaining lines by a judicious selection, so that they would have been rendered more profitable to the country, while these six millions would have remained for investment. With this money at its disposal, our Government might now have had the following lines for conveyance of mails, which it eminently wants, viz., a mail line from Exeter to Plymouth, and its continuation for the same purpose to Falmouth; a mail line to Ireland by way of Chester and Holyhead; and a mail line north to Scotland. These great lines would have been feeders to those which already exist, would have conferred great benefits on the country, and would have cost no more than has been already paid for partial communication."

The Athenæum was not alone in hymning the blessings of State control. The Artisan for July points out that the railways of Belgium possess a great advantage over the railways of this country in the economy of their construction owing to the authority of Government, and further, "on the all-important point of safety, the system of State management, as exemplified in the railways of Belgium, far surpasses the railways of England." Convinced, however, that State control, whatever its abstract virtues, was alien to the English temperament, the writer goes on to consider whether there is no mean course available. "We turn to France, and find there is a system adopted which promises to secure the advantages of encouragement by the State with the independence of individual control."

We too can now turn to France, and, with the benefit of experience to guide us, can prove the pudding that the French people have had the privilege of eating for the last five-and-forty years. And to-day there can be but one opinion among those competent to judge, even those who are most dissatisfied with our English railways, that the public, whether as passengers by first, second, or third class, or as shippers of goods, either by grande or petite vitesse, are immeasurably worse served than they are in England. As for the system on which the French lines have been built—a system by which the Government guarantees dividends ranging from 7 to 12 per cent., and dare not call upon the companies to carry out obviously necessary extensions, lest it should in its turn be called on to make good its extravagant guarantee, while the companies, secure in the possession of a monopoly which yields them without effort an income far larger than even this guaranteed minimum, have no inducement to weight themselves with comparatively unproductive new lines—now that the Artisan is unfortunately defunct, it would be difficult to find for it one solitary supporter.

The entire unconsciousness even of the railway men themselves of the revolution they were working is nowhere better shown than in the different methods that were proposed for conducting the traffic. Practically the locomotive, as we have it to-day, capable of working up to 1000 horse-power, was already there. The multitubular boiler and the steam-blast had long been in common use. But neither the public nor the specialists were convinced that the right system had been hit upon. To say nothing of a "patent aerial steam-carriage which is to convey passengers, goods, and despatches through the air, performing the journey between London and India in four days, and travelling at the rate of 75 to 100 miles per hour," all kinds of substitutes for locomotives were being sought for. One day the Globe reports that a "professional gentleman at Hammersmith has invented an entirely new system of railway carriage, which may be propelled without the aid of steam at an extraordinary speed, exceeding 60 miles an hour, with comparative safety, without oscillation, which will no doubt become the ordinary mode of railway travelling for short distances, as the railway and carriages may be constructed and kept in repair for less than one-fourth of the usual expense." Another day the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway have, says a Scotch writer, "the discernment to employ Mr. Davidson, a gentleman of much practical knowledge and talent, "to construct for them an electro-magnetic carriage. The carriage, 16 feet long by 7 feet wide, was duly placed upon the rails, and "propelled by eight powerful electro-magnets, about a mile and a half along the railway, travelling at the rate of upwards of 4 miles an hour, a rate which might be increased by giving greater power to the batteries, and enlarging the diameter of the wheels." "The practicability of the scheme is," we are assured, "placed beyond doubt," and its "simplicity, economy, safety, and compactness render it a far more valuable motive power than that clumsy, dangerous, and costly machine the steam-engine."

Then, again, Messrs. Taylor and Conder, C.E., patented an ingenious system by which a carriage was to be drawn along the line "by the muscular power of the two guards who, as it is, constantly accompany it." The system, which is at the present moment in use for towing purposes on many German rivers, the Elbe for one, required that an endless rope should be laid along the line, and wound on to a drum which was attached to the carriage, and made to revolve by force, manual or mechanical, supplied from inside the carriage itself. Next Mr. England, the engineer of the London and Croydon Railway, made a manumotive railway carriage, "very light and elegant in appearance, and capable of carrying seven or eight persons at the rate of 18 miles an hour." "We have no doubt," says a railway newspaper, "that these machines will come into general use, as they will effect considerable saving to the company in the expense of running an engine." Unfortunately none of these fine promises came to much. Mr. England's manumotive carriage, under the more humble name of a trolley, is often employed on country lines to convey navvies or surface men to or from their work. And the endless rope and drum system is in some instances of unusually steep inclines used to let a train down into a station, but it can hardly be said to have revolutionised railway travelling. Mr. Davidson, like many another inventor, was rudely checked by the cost of experiments and the stringency of the Patent Laws; and, after forty more years have been devoted to their improvement, electric railways are still hardly better than a scientific toy.

The aerial steam carriage, a most formidable affair, with a frame 150 feet long by 30 feet wide, covered with silk, and a tail 50 feet in addition, went so far as to get itself patented. "We learn from those who have seen it," writes the Spectator, "that the Pegasus is actually in being. Its form has been delineated, and, if correctly, bold must be the man who will venture astride. With body stretching for many a yard, with tail lifted far aloft, with wings of copper like revolving shields, and with fire and smoke issuing from its head, no griffin it was the lot of St. George to encounter ever presented form so vast and terrible." This fire-breathing monster (so Samuel Rogers said) only resembled a bird in one respect—it had a bill in Parliament, presented by the honourable and learned member for the city of Bath. On one occasion, however, in the lively imagination of a writer in the Glasgow Constitutional, who succeeded in hoaxing several of its English contemporaries, it had a most prosperous trial trip.

The locomotive had, however, more serious competitors than these. The London and Blackwall Railway was worked by stationary engines, dragging the carriages with one wire rope for the up and another for the down traffic, each having a total length of about eight miles and a weight of 40 tons. And on this line, among the first, the electric telegraph was used, in order that the engineer at Blackwall or Fenchurch Street might know when to begin to wind up or let go his rope. The system in use was certainly most ingenious. A down train, as it left Fenchurch Street, consisted of seven carriages. The two in front went through to Blackwall; the next carriage only as far as Poplar, and so on to the seventh, which was detached at Shadwell, the first station after leaving Fenchurch Street. As the train approached Shadwell, the guard, standing on a platform in front of the carriage, pulled out "a pin from the coupling at an interval of time sufficient to let the carriage arrive at its proper destination by the momentum acquired in its passage from London." The same process was repeated at each subsequent station, till finally the two remaining carriages ran up the terminal incline, and were brought to a stand at the Blackwall Station. On the return journey the carriage at each station was attached to the rope at a fixed hour, and then the whole series were set in motion simultaneously, so that they arrived at Fenchurch Street at "intervals proportioned to the distance between the stations." On the up journey the Blackwall portion of the train consisted of four carriages, there being, so to speak, a "slip-coach" for Stepney and another for Shadwell, and this seems to have been the nearest, and in fact the only, approach to an attempt to deal with traffic between intermediate stations. But the wear and tear was too much; there were perpetual delays, owing to the rope breaking, and the cost of repairs and renewals was something immense.

The Sunderland and Durham also was worked with a rope, at first of hemp and afterwards of wire, as was and still is the Cowlairs tunnel on the Edinburgh and Glasgow line. On other similar local lines, such as the Edinburgh and Dalkeith, or the Dundee and Arbroath, the carriages were still drawn by horses. In Ireland, again, the continuation of the Dublin and Kingstown Railway on to Dalkey, which was worked by atmospheric engines, was just being opened for traffic, a speed of about 30 miles an hour having been successfully obtained on several trial trips. It was proposed to work the line from Exeter to Plymouth by water power. Water power, however, was abandoned, and the atmospheric system adopted, and this was so far at least a success, that on one occasion the 8 miles between Exeter and Starcross were said to have been covered at the rate of 70 miles an hour. An American inventor, Mr. Bissell, had constructed a pneumatic locomotive, to be driven by compressed air stored in reservoirs at a pressure of 2000 lbs. to the square inch.

Even where steam locomotives were employed, "the slowness to believe in the capabilities of the locomotive engine, exhibited by the engineers of Great Britain is (the quotation comes from the Athenæum, of April 22nd, 1843) "surprising . . . Want of faith in the capabilities of the locomotive engine has formed one important item in the cost of the English railway system. Engineers set out in their railway career with the impression that the locomotive was ill calculated to climb up hill with its load, and that therefore, to work with advantage, it must work on lines altogether level, or nearly so; hence mountains required to be levelled, valleys filled up, tunnels pierced through rocks, and viaducts reared in the air,—gigantic works at a gigantic cost, all for the purpose of enabling the engine to travel along a dead level, or nearly so. But here, again, was want of faith in the power of the locomotive engine. The locomotive engine can climb the mountain-side as well as career along the plain." So wrote the Athenæum in 1843, and so, in fact, it was proved in the next few years, when the Lancaster and Carlisle was carried over Shap Fell at a height of 915 feet above the sea, with a gradient of 1 in 75 for 4 miles, and the Caledonian climbed for 10 miles at a gradient of 1 in 80 to Beattock Summit, 1015 feet above sea-level.

Still, even as early as this time, when trains out of Euston and Lime Street, Liverpool, were hauled up by stationary engines, and the up trains through the Box Tunnel were assisted by a second engine behind, there were some lines where locomotives had every day the opportunity of showing that they could "climb the mountain-side." Here is the Durham Advertiser's account of the matter: "Let those who are sceptical as to the practicability of constructing a railway to profit over a hilly country, without encountering the enormous cost of securing what are called 'easy gradients', visit the Hartlepool Railway, where they will find a locomotive engine with its tender pulling a train of three or four passenger carriages up a short inclined plane of 1 in 30 and two long inclined planes of 1 in 35, at velocities of from 20 to 25 miles per hour, four times in the day; and the only obstacle to its ascent (with still greater weights) appears to arise from the slipping of the wheels, or their want of adhesion to the rails in wet weather. This engine is furnished with 14-inch cylinders and six 4½-feet wheels coupled together. Who, then, shall venture to assert that railways will not hereafter be laid over the rough surface of any country hitherto deemed inaccessible by them? If the tread or tire of the wheels of such a locomotive were considerably widened, and the main rails upon such inclined planes laid upon longitudinal sleepers and"—here comes in the curious lack of faith that the Athenæum so justly reprobates—"an extra rail of wood or rough—why not cogged?—iron fixed outside the main rail, to which the tire of the engine (but not the carriages) wheels should extend, their adhesive power, we imagine, might be doubled . . . 'Nil mortalibus arduum est,' we exclaimed, whilst flying up one of those Hartlepool inclined planes last week." (Of the Lickey incline, on the Birmingham and Gloucester, which was opened in 1840—1 in 37 for 2 miles—I shall have something to say in the chapter on the Midland Railway.)

But, though the Athenæum said truly that the monumental lines of Stephenson and Brunel ought never to have been built in the style they were for the traffic of 1843, time has proved that, after all, the engineers were right, though they did not know it, and the philosophers were wrong. For to its splendidly straight and level track the North Western owes it that it can with ease keep abreast of the utmost efforts of its energetic rivals, the Great Northern and the Midland, in the race to Manchester; while the Great Western finds in the same circumstance ample compensation for the fact, that its line to Exeter is no less than 23 miles further than the rival route. Meanwhile, the day of monumental lines was over, and the projectors of new routes were being compelled by the prevailing depression to cut their coats according to their cloth, and content themselves with schemes much more moderate than those with which they would have been satisfied a few years before. Unconvinced, however, that locomotives could climb gradients, they were still in search of contrivances scarcely less impracticable than the cogged wheels and movable legs of an earlier generation, in order to overcome their imaginary difficulties. One ingenious gentleman went so far as to suggest that, though the engine should have wheels to keep it on the line, the weight should be carried, and the driving power should be applied to rough rollers running upon a gravel road, maintained at a proper level between the two rails. By this method alone, he was convinced, would sufficient bite of the ground be obtained to enable a locomotive to draw a paying load up an incline. Another engineer proposed that on gradients steeper than 1 in 100 a second rail should be introduced, inside the ordinary one, on which the flange of the driving wheels, specially made rough for this purpose, might bite more firmly.

On the other hand, Lieutenant Le Count, R.E., of the London and Birmingham Railway, whose book is a mine of information in ancient history, writes as follows: "The want of adhesion, so much talked of, is found to be only nonsense, and, if there had been any, it would only be necessary, as the writer of this article suggested several years ago, to connect a galvanised magnet with one or more of the axles to act on the rails, by which means, with the addition of only a few pounds, an adhesion equivalent to the weight of two tons would be produced at each axle, being capable also of acting or not at a moment's notice." Lieutenant Le Count was sceptical on another point also. The puny little 'Goliaths' and 'Samsons' with a boiler pressure of some 40 lb. as against the 140 to 180 lb. of to-day, were sometimes brought to a standstill by a fall of snow. But "the plans so often proposed," he writes, "of sweeping or scraping the rails will rarely be found necessary, much less the plan seriously proposed and patented so late as 1831, of making the rails hollow and filling them with hot water in winter."

The tentative condition of the engineering knowledge of the time cannot be better exemplified than by a glance at a sketch furnished to the Railway Times in January, 1843, by an engineer as distinguished as Mr. Crampton. This sketch, which is reproduced below, "shows safety or reserve wheels, not running upon the rails while the engine is ordinarily at work, and not therefore liable to suffer. They are provided with deep flanches (sic), which act as a guide for the engine in the event of accidents . . . It will be obvious," writes Mr. Crampton, "that, should either axle break, the weight would be immediately supported by the reserve wheels, and the safety of the engine insured."

But there was another advantage, Mr. Crampton thought: "By this arrangement I am enabled to place the boiler considerably lower than in the engines commonly used, which allows the use of much larger driving wheels, without endangering the safety of the engine, and also reduces the rocking and pitching motion, to which engines having the centre of gravity placed high are continually subject." Such was the universally accepted ancient theory, a theory which probably accounted for Mr. Harrison's patent of 1837, as to which I shall have something to say in the chapter on the Great Western Railway, and which certainly in 1847 led to Mr. Trevithick building the famous old 'Cornwall' with her boiler beneath the driving axle. Modern practice, however, has shown that engines with a high centre of gravity not only run more smoothly and are less hard upon the permanent way, but actually are safer in running round sharp curves at a high rate of speed.

Still, in spite of all these difficulties and hesitations, railways were steadily taking more and more hold of the public life and habits. In February, 1842, the Morning Post writes: "It is worthy of remark that Her Majesty never travels by railway. Prince Albert almost invariably accompanies the Queen, but patronises the Great Western generally when compelled to come up from Windsor alone. The Prince, however, has been known to say, 'Not quite so fast, next time, Mr. Conductor, if you please.'" His Royal Highness must have got pretty rapidly acclimatised, as in July, 1843, he came up from Clifton to Paddington within three hours. The Queen herself could not hold out much longer, and on June 18th, 1842, the Railway Times records: "Her Majesty made her first railway trip on Monday last on the Great Western Railway, and we have no doubt will in future patronise the line as extensively as does her Royal Consort. The Queen Dowager, it is well known, is a frequent passenger by the London and Birmingham Railway, and has more than once testified her extreme satisfaction with the arrangements of the Company. On Wednesday last her Majesty Queen Adelaide went down by the South Western Railway for the first time en route for the Isle of Wight." Her Majesty returned a few days afterwards, and accomplished the 78 miles between Southampton and Vauxhall in one minute under the two hours,—a run of which the South Western authorities were evidently not a little proud. And one must admit that they had a right to be so. It was not till July, 1888, that the present generation had a chance of getting to Southampton in so short a time. Not long afterwards, however, another "special" ran the distance in one hour and forty-six minutes. But the run must have been a pretty rough one, with little four-wheeled carriages loosely fastened together with couplings such as the one figured below.

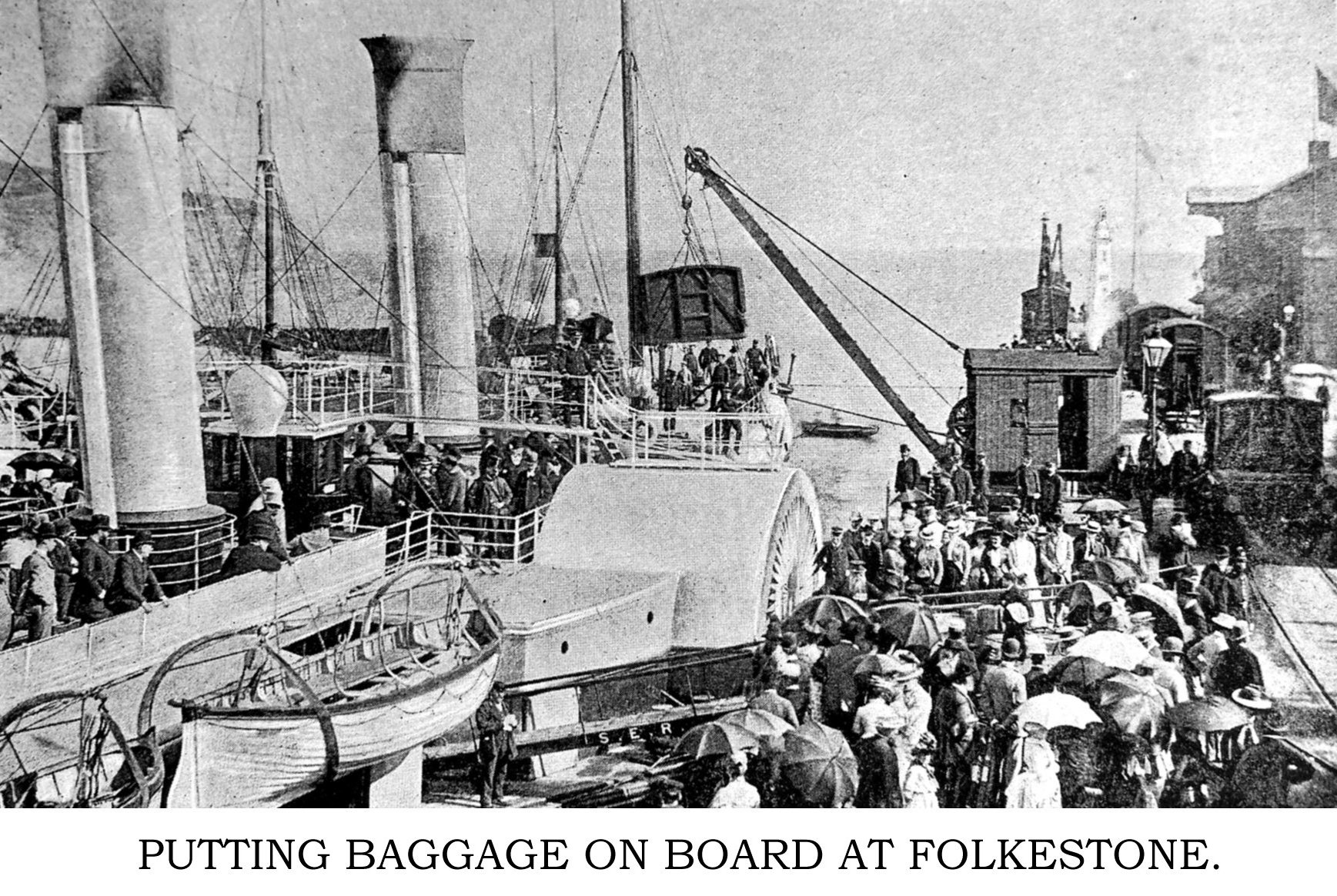

Queen Victoria apparently found a railway journey not as bad as she had fancied it, as on Saturday, July 23rd, she returned from London to Slough by the Great Western, "accompanied by his Royal Highness Prince Albert, their Serene Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Saxe Coburg Gotha, and a numerous suite." The Duke of Wellington took even longer to convert. It was not till August, 1843, that, being then in attendance on the Queen, he was compelled to take his first trip by rail to Southampton. On this occasion there were, it is reported, "the unprecedented number of eight specials (four each way) in addition to the ordinary traffic, twenty-seven trains in the day, including goods trains." Six weeks later there is this note: "We are glad to find that the Duke of Wellington's first trip on the South Western Railway, in attendance on Her Majesty, has reconciled his Grace to the new mode of travelling. Last week his Grace passed from and to Folkestone in one day by the Dover line."

But trains were not good enough even yet for foreign royalties. As late as July, 1843, the Globe translates from the French journal Le Commerce the following story of Louis Philippe:—"When the King was intending to go with the Royal Family to his chateau at Bizy, he proposed to be conveyed by a special train on the railway as far as Rouen, and orders were given to this effect; but the Council of Ministers, on being acquainted with his Majesty's project, held a sitting, and came to the resolution that this mode of travelling by railway was not sufficiently secure to admit of its being used by the King, and consequently his Majesty went to Bizy with post-horses. This, it must be acknowledged, is a singular mode chosen by the Cabinet for encouraging railways." No doubt the frightful Versailles accident of the year before, in which fifty passengers were burnt to death, had something to do with this decision of his Majesty's ministers. It certainly gave rise to Sydney Smith's celebrated letter as to the necessity of sacrificing a bishop to secure the doors of the carriages being left unlocked. A correspondent of the newspapers, however, persisted that, "in spite of Socrateses, Solons, and Sydney Smiths, wise in their own conceit," locking in was right, while a second considered that the letter "showed a good deal of apparent prejudice, and something of irreverent and inappropriate wit, unbecoming a Christian minister." About the same time it is recorded that the Judges, sent down as a Special Commission to try some rioters at Stafford, went by special train from Euston. "It would appear, therefore," says the Railway Times, "that travelling by railway is not now considered beneath the dignity of the profession." On the other hand, Lord Abinger, presiding in the Court of Exchequer, said, "It would be a great tyranny if the Court were to lay down that a witness should only travel by railway. If he were a witness, in the present state of railways, he should refuse to come by such a conveyance."

Perhaps Lord Abinger and Louis Philippe's ministers might be forgiven if they were disinclined to accept "the present state of railways" as altogether satisfactory. Here is what Mr. Bourne, a professed panegyrist of the new system, describes as a typical experience as late as the beginning of 1846: "It requires perhaps some boldness to claim for a mere piece of machinery, a combination of wheels and pistons, familiar to us by frequent use, any alliance with the sublime. Let the reader, however, place himself in imagination upon the margin of one of those broad dales of England, such for example as that of Barnsley in Yorkshire, of Stafford, or the vale of Berks, up each of which a great passenger railway is carried, and over which the eye commands an extended view. In the extreme distance a white line of cloud appears to rise from the ground, and gradually passes away into the atmosphere. Soon a light murmur falls upon the ear, and the glitter of polished metal appears from time to time among the trees. The murmur soon becomes deeper and more tremulous. The cloud rises of a more fleecy whiteness, and its conversion into the transparent air is more evident. The train rushes on; the bright engine rolls into full view; now crossing the broad river, now threading the various bendings of the railway, followed by its dark serpent-like body. The character of the sound is changed. The pleasant murmur becomes a deep intermitting boom, the clank of chains and carriage-fastenings is heard, and the train rolls along the rails with a resonance like thunder.

"Suddenly, a wagon stands in the way, or a plank it may be has been left across the rails; a shrill, unearthly scream issues from the engine, piercing the ears of the offending workmen, and scarcely less alarming the innocent passengers. Many a foolish head is popped out of the window, guards and brakesmen busily apply their drags, and the driver reverses the machinery of his engine, and exerts its utmost force, though in vain, to stop the motion. The whole mass fairly slides upon the rail with the momentum due to some sixty or seventy tons. Then comes the moment of suspense, when nothing remains to be done, and it is uncertain whether the obstacle will be removed in time. It is so; and the huge mass slides by with scarcely an inch to spare. Off go the brakes, round fly the wheels, the steam is again turned on, and the train rolls forward at its wonted speed, until smoothly and silently it glides into the appointed stopping-place. Then comes the opening of doors, and the bustle of luggage-porters. Coaches, cabs, omnibuses, vehicles of every description, fill and rapidly drive off, until before ten minutes have elapsed the uncouth engine has slunk back into its house, and some hundred passengers, with their luggage, have disappeared like a dream, and the platform is once more left to silence and solitude."

Queen and Judges could please themselves as to whether they went by train or not. But for the mass of Her Majesty's subjects it was fast becoming a case of Hobson's choice. The "highways were unoccupied." The turnpike tolls from Swindon to Christian Malford in Wilts, which had been let at £1992 in 1841, only produced £654 in 1842. For the tolls on the road between Wakefield and Sheffield not a single tender was sent in, and the trustees were compelled to collect them themselves. The forty coaches which had run daily through Northampton were all dead within six months of the opening of the London and Birmingham. Almost every week came a notice that some famous line of coaches had ceased to run. Here is one under date October 15, 1842: "A few years since 94 coaches used to pass through St. Albans daily. On Saturday last the Leeds express, formerly called the 'Sleepy Leeds,' which has been on the road upwards of a hundred years, ceased running, it being no longer a profitable speculation, and it is said another out of the four remaining is likely soon to follow the example." Six weeks later we read, "the mail from Worcester to Ludlow, after running for half a century, made its last journey on Tuesday, November 29th, thus leaving the public without official conveyance for letters from Worcester to Tenbury."

Another day the papers record the death of the Peak Ranger, "which had stood high in the estimation of the public," on the road between Sheffield and Manchester. "On Saturday last, when drawing near to Sheffield, its inevitable dissolution became apparent, and Mr. Clark, who was driving, almost despaired of reaching the terminus before death put a period to its existence; fortunately, however, the task was accomplished, and a few minutes after its arrival it quietly departed this life without a struggle or a groan. Report says that its remains are about to be sent by railway to the British Museum in London, where it will be exhibited as a relic of antiquity for centuries to come. Unfortunately for the coachman, he was, owing to this dreadful calamity, left at Sheffield, a distance of 24 miles from home. Every inquiry was made for a vehicle to convey him home. The Leeds Railway was recommended, but this he rejected in terms of bitter resentment, when fortunately it was discovered that one solitary wagon was still permitted to travel on that road. Having been snugly packed in the tail of the wagon, he was safely delivered at his own door within twenty-four hours after the fatal catastrophe."

Here is a similar obituary notice dated July 18, 1843: "Died, after a long and protracted existence, the near leader of the 'Red Rover,' the last of the London and Southampton coaches. The symptoms of decay, which ended in the event we now record, set in on the day the South Western Railway opened, the severe grief produced by which brought on an affection of the heart, which, acting upon a frame not of the strongest, induced the calamity so much deplored by the inconsolable proprietors. The fact became known on Monday last, the previous four-in-hand having dwindled that morning to three. The physician who has attended the case has given his opinion that change of air is immediately necessary to save the remaining portion of this 'Red Rover' family. It would macadamise the whole of the city stones to witness the disconsolate appearance of the solitary leader. Certainly steam has much indeed to answer for!"

And here yet another from the Eastern counties:—"The days, nay, the very nights, of those who have so long reined supreme over the 'Phenomena' and 'Defiances,' the 'Stars' and the 'Blues,' the 'Flys' and the 'Quicksilvers,' of the Essex Road, are at an end. Their final way-bill is made up. It is 'positively their last appearance on this last stage.' This week they have been unceremoniously pushed from their boxes by an inanimate thing of vapour and flywheels, by a meddling fellow in a clean white jacket, and a face not ditto to match, who, mounted on the engine platform, has for some weeks been flourishing a red-hot poker over their heads in triumph at their discomfiture and downfall; and the turnpike road, shorn of its gayest glories, is desolate and lone. The coachmen, no doubt, 'hold it hard,' after having so often 'pulled up,' to be thus pulled down from their high eminences, and compelled to sink into mere landlords of hotels, farmers, or private gentlemen. Yet so it is. They are 'regularly booked'—'their places are taken' by one who shows no disposition to make room for them, even their coaches are already beginning to crumble into things that have been; and their bodies—we mean their coach-bodies—are being seized upon by rural-loving folk for the vulgar purpose of summer-houses. But a few days and they will all vanish,—

In March, 1842, a few weeks after the opening of the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, the Glasgow Courier reports: "The whole of the stage coaches from Glasgow and Edinburgh are now off the road, with the exception of the six o'clock morning coach, which is kept running in consequence of its carrying the mail-bags." For Lord Lowther, the then Postmaster-General, seems to have thought, like Louis Philippe's ministers, that railways were not safe enough to be intrusted with Her Majesty's mails, and the papers are full of complaints that sufficient advantage is not taken of the rapidity of railway communication in the conveyance of letters. The Brighton coaches having been driven off the road by the opening of the railway in 1841, the mails were sent down from London in a cart, in spite of an indignant memorial from Brighton residents, who protested that such a mode of conveyance was "neither safe nor respectable." Next year, however, the Brighton Railway Company raised its fares, and encouraged some coaches to enter again upon the unequal struggle. And something similar happened on the road from Liverpool to Warrington and from Liverpool to St. Helen's.

In May, 1843, the battle in the Home Counties was so far decided, that a newspaper reports: "Only eleven mail coaches now leave London daily for the country. A few years since, before railways were formed, there were nearly eighty that used to leave the General Post Office." Even when the coaches had not been driven off the road altogether, they had been forced in many places to lower their fares. The fares from London to Birmingham had been 50s. in and 30s. outside. The opening of the railway brought them down to 30s. and 17s. respectively. Though there was no railway nearer than the Southampton line, the outside fare from Salisbury to London had already come down from 20s. to 13s. Punch, taking as usual the popular view, declared that the only thing left for the stage proprietors was to emigrate to "Coachin-China." In fact, however, Lord Hardwicke, in advocating the construction of a new line in Cambridgeshire, brought forward the returns of turnpike receipts—in the neighbourhood, one must presume, of the great towns—and post-horse duty, to show that the increase of short-distance and cross-country traffic had more than counterbalanced the diminution on the great main roads.

Every one has heard of the 2000 post-horses that used to be kept in the inns at Hounslow. As early as April, 1842, a daily paper reports: "At the formerly flourishing village of Hounslow, so great is now the general depreciation of property, on account of the transfer of traffic to the railway, that at one of the chief inns is an inscription, 'New milk and cream sold here;' while another announces the profession of the chief occupier as 'mending boots and shoes.'" "Maidenhead," writes an Old Roadster, "is now in miserable plight. The glories of 'The Bear,' where a good twenty minutes were allowed to the traveller to stow away some three or four shillings' worth of boiled fowls and ham to support his inward man during the night, are fast fading away for ever. This celebrated hostelry is about to be permanently closed as a public inn." Here is a yet more important effect of railways, according to the Berks Chronicle: "The heath and birch-broom trade, which used to be of very considerable extent at Reading Michaelmas Fair, and from which many of the industrious poor profited, has fallen away to a mere nothing. When the dairymen had their cheese brought up the old road, they used to load the wagons home with brooms; but now, since the mode of conveyance is changed to the railway, it does not answer the purpose of the dealers to pay the carriage for them by that mode of transit."

Nor were coachmen, inn-keepers, and broom-cutters the only people who suffered from the change. The shopkeepers of Ashton-under-Lyne, Stockport, and other small towns round Manchester complained bitterly that their customers all went into Manchester to shop, and that they were left to sit idle. Canals had in some places fared no better. By the opening of the Manchester and Leeds line, the value of the Rochdale Canal shares came down in two years from £150 to £40. The shares of the Calder and Hebble Navigation had been worth 500 guineas; they were now being freely offered at about £180.

On the other hand, new trades were springing up on all sides. One day it is recorded in a Liverpool paper that a Cheshire farmer has ceased to make cheese, and is supplying the Liverpool market with fresh milk, "conveying this nutritious article from a distance of over 43 miles, and delivering the same by half-past eight in the morning." Another day readers are startled to learn that wet fish from the East coast ports can be delivered fresh in Birmingham or Derby. A tenant on the Holkham estate bears witness to the advantage of a railway to the Norfolk farmers. His fat cattle, so he said, used to be driven up to London by road. They were a fortnight on the journey, and when they reached Smithfield had lost three guineas in value, besides all the cost out of pocket. As soon as the Eastern Counties line was opened, he would send his cattle through by train in twelve hours. The farmers, in fact, seem to have taken kindly to the new order of things. For the great Christmas cattle market in 1843, the London and Birmingham brought up in two days 263 wagons, containing 1085 oxen, 1420 sheep, and 93 pigs.

A good many of the notices remind us that the experience of the last few years is not the first revolution that the English agricultural interest has encountered and survived. Under the heading, "A New Trade in Darlington," the Great Northern Advertiser chronicles: "During the past month [November, 1843] vast numbers of sheep have been slaughtered by the Darlington butchers, and have been sent per railway to London." Here is a second from the same neighbourhood: "The 'Butter Wives' frequenting Barnard Castle market were not a little surprised on Wednesday se'nnight, to discover that through the facilities offered by the railways, a London dealer had been induced to buy butter in their market for the supply of the cockneys, and in consequence the price went up 2d. per pound immediately. This rise, however, did not deter the agent from purchasing, and 2000 pounds of butter were quickly bought, sold, and packed off for the great Metropolis, where it would again be exhibited, and sold to the London retailers by five o'clock on Friday morning.'' And here is the result: "At a meeting of the Statistical Society a paper was read on the agricultural prices of the parishes of Middlesex . . . The writer proceeded to say that the railway had greatly affected prices in the cattle market at Southall and had occasioned much discontent among the farmers, who complained that, in consequence of the facility that it afforded for the rapid transfer of stock from one county to another, they had been deprived of the advantages which they formerly possessed from their proximity to London. Five hundred head of sheep and 100 head of cattle had upon more than one occasion been suddenly introduced into the market from the West of England, and prices had been proportionably forced down."

But, as a rule, on the great through lines, in 1843, everything except passenger traffic was a very secondary affair. The Great Western was earning £13,000 a week from passengers and only £3000 from goods. On the London and Birmingham the goods receipts were much the same, but the passengers returned some £15,000. On this latter line, for the first five months of its existence, the passenger receipts were about £130,000, while the total goods earnings were £2,225 9s. 3d. On the South Western the proportion was six to one; on the Brighton more than seven to one; on the South Eastern more than ten to one. Even on the Midland Counties and North Midland, where nowadays passengers are far less important than goods and minerals, five-eighths of the whole receipts came from the "coaching" traffic. Of course there were exceptions; on a purely mineral line, such as the Taff Vale, the goods receipts were five-sixths of the total, while on the Newcastle and Carlisle they were two-thirds. Still, taking England as a whole, the goods traffic was only about a quarter of the total, instead of three-fifths, as it is to-day. But the Great Western Railway is reported to be making arrangements to bring up Bath stone in large quantities from the quarries at Box, and the carriage of coal to London by rail had already begun. As early as 1838 a Select Committee of the House of Commons had only failed by one vote to adopt the recommendation of Lord Granville Somerset that the coal dues should be discontinued. The majority against their abolition was composed, according to the Railway Times, of two aldermen of the City of London, three coal-owners, and one coal-factor. In those days, however, the Metropolitan Board of Works as yet was not; the Corporation took the whole of the dues, and was under no obligation to spend them upon Metropolitan improvements.

The express and through trains on the great lines, such as the Great Western or the London and Birmingham, were timed to run at something between 20 and 30 miles an hour. From London to Bristol, for example, 118 miles, the train took four hours and a quarter, the same time that the 'Dutchman' now takes to reach Exeter, 76 miles further. The 6 a.m. from Euston, described as "a quick train throughout," reached Liverpool, viâ Birmingham and Newton Junction (210 miles), at 4 p.m. and Darlington, viâ Derby and York, at 7 p.m. It was thought a great feat that the Times, on one occasion when it contained important news just arrived by the Indian Mail, was delivered in Liverpool to catch the American packet at 2.15 p.m., having been sent forward from Birmingham on a special engine. Shortly after, however, the incoming mail was sent up to London in six hours and three-quarters. The Newcastle Courant chronicles, as "remarkable proof of the wonders of steam travelling" that Lord Palmerston's mare Iliona ran at Newcastle on Wednesday, and at Winchester on Friday. "The distance thus travelled was nearly 400 miles, and the time 32½ hours, of which between nine and ten were spent in London." Here is a somewhat similar notice, heading and all, from the Mechanics' Magazine in January, 1842: "ALL TRIUMPHANT STEAM.—The 'Great Western' fired her signal of arrival in Kingroad (ten miles from Bristol at the mouth of the river) at half-past ten on Monday night, in thirteen days only from New York. The reporter of the Times went on board, and left her again in an open boat and in a gale of wind before eleven. He reached London by the mail train at half-past five. The intelligence was printed and despatched again to Bristol by one of the regular trains, and a copy of the Times was in the cabin of the 'Great Western,' in the roadstead, by 10 o'clock p.m. These are the wonders of steam navigation; steam travelling, and steam printing."

But these times would have been much faster had it not been for the long and frequent stoppages. There was a stoppage for refreshments at Wolverton, half-way from London to Birmingham, and another at Falkirk, on the 47-mile journey between Edinburgh and Glasgow. When they were actually in motion, trains could go fast enough. We have already mentioned a run from Southampton to London at the rate of over 43 miles an hour. A special run from Liverpool to Birmingham with American despatches, 97 miles in 150 minutes, was scarcely slower, and the Grand Junction was a line more famed for dividends than for speed. Lord Eglinton's trainer, in order to be in time for a race, took a "special" from Manchester to Liverpool, 30 miles in 40 minutes, or at the rate of 45 miles an hour. Another "special" ran from Derby, 40 miles in 66 minutes, of which 16 were spent in three stoppages. A third, from Brighton to Croydon, 40 miles in 50 minutes. And there is abundant proof that the light trains of those days (two small coaches and a guard's van probably) could, if necessary, get along nearly as fast as our own ponderous expresses, which must be not unfrequently quite twenty times as heavy. Here is a table from a paper read before the Statistical Society in the spring of 1843. It may be presumed, however, that third class trains are not included in calculating the averages.

It was a not uncommon custom, if any important person missed his train, to charter a "special" and start in pursuit. With good luck he might count on overtaking a train which had only had half an hour's "law," before it had got much more than half the distance between London and Brighton. On one occasion the Secretary of the London and Greenwich Railway, having missed the train, mounted an engine, and started in such hot pursuit, that he ran into the tail carriage with sufficient violence to break the legs of one or two passengers.

The Edinburgh Chronicle must take the responsibility of vouching the truth of the story that follows: "A gentleman, on urgent business in Glasgow, arrived at the Edinburgh station on Monday morning, just as the 9 o'clock train had started. A special engine was engaged, and, starting at half-past nine o'clock, overtook the train at Falkirk at 10 minutes past 10 o'clock, running the 23 miles in 40 minutes, 15 minutes of which time was occupied in stopping at three of the stations; the 23 miles were thus traversed in 25 minutes, being at the enormous speed of 55 miles in an hour." More remarkable yet is the statement of a correspondent of the Railway Times, who gives his name and address as "George Wall, Sheffield, 7th December, 1843": "I have frequently timed trains to 60 to 65 seconds to the mile, and on one occasion a train ran 3 miles in 53, 54, and 55 seconds respectively, giving an average of 54 seconds per mile, or 59½ miles per hour. (Sic in original. In fact it is 66⅔.) In this last case two other passengers marked the time, along with me, by our own watches, and we were all agreed." It perhaps helps us to understand why trains, which could travel on occasion as fast as this, were not timed faster in every-day working, to read that among the indispensable appliances on a railway were included trucks on which to convey broken-down engines, and also a suggestion that a trolley should always be attached in front of the engine, that it might be ready at hand to fetch assistance in case of a break-down. (I find a contemporary allusion to a practice (described as "almost universal before the recent improvements in engine building") of putting oatmeal or bran, or, if these could not be had, horse-dung, into the boiler, in order to stop the leaking of the tubes.)

But high speed was impossible over any long distance except when extraordinary preparations had been made beforehand. Even three years after this time, it was looked upon as a remarkable feat that Mr. Allport travelled from Sunderland to London and back—with relays of "specials" in waiting at Darlington, York, Normanton, Derby, Rugby, and Wolverton—600 miles in 15 hours. Not only were the engines too small to run more than 20 or 30 miles without taking in water, but there were numerous spots where the permanent way was not wholly to be trusted. Here it had shown a tendency to subside, there the sides of a cutting looked like slipping. Maidenhead Bridge was said to be unsafe; if Dean Buckland could be trusted, even the Box Tunnel was not above suspicion. In the absence of all signalling, except by hand, innumerable points such as these would need that speed should be slackened.

Dean Buckland was not alone in suspecting the Box Tunnel. The public mind was so uneasy on the subject, that General Pasley was sent down by the Board of Trade to make a special inspection. He reported it sound and safe, and added "that the concussion of air from the passage of the locomotive was not likely to endanger the safety of passengers" by bringing down the roof where the tunnel was cut through the live rock without the arch being bricked. No doubt the mere fact that it was a tunnel was enough to make many people suspect it. In January, 1842, the Glasgow Argus reported, in reference to the Cowlairs Tunnel on the Edinburgh and Glasgow, that "as the lamps, 43 in number, will be kept burning night and day during the passage of the various trains, the dull, cheerless, and to many alarming, feelings which passing through a dark tunnel usually excites will be entirely removed, the effect being little else than the passage through a somewhat narrow street. The tunnel presents a very splendid appearance, while it creates a feeling of the utmost security, although the spectator is conscious of the immense superincumbent masses of rock and other strata which are resting above him."

A year or two earlier it needed more than mere gas lights to reassure the British public. "The deafening peal of thunder," said one medical authority, "the sudden immersion in gloom, and the clash of reverberated sounds in a confined space, combine to produce a momentary shudder, or idea of destruction, a thrill of annihilation." Here is what Lieutenant Le Count found it necessary to publish as to the London and Birmingham:—"So much has been said about the inconvenience and danger of tunnels, that it is necessary, whilst there are yet so many railways to be called into existence, to state that there is positively no inconvenience whatever in them, except the change from daylight to lamplight. This matter was clearly investigated and proved upon the London and Birmingham Railway, a special inspection having been there made in the Primrose Hill Tunnel by Dr. Paris and Dr. Watson, Messrs. Lawrence and Lucas, surveyors, and Mr. Phillips, lecturer on chemistry, who reported as follows: 'We, the undersigned, visited together, on the 20th of February, 1837, the tunnel now in progress under Primrose Hill, with the view of ascertaining the probable effect of such tunnels upon the health and feeling of those who may traverse them. The tunnel is carried through clay, and is laid with brickwork. Its dimensions, as described to us, are as follows: height, 22 ft.; length, 3750 ft.; width, 22 ft. It is ventilated by five shafts from 6 to 8 ft. in diameter, the depth being 35 to 55 ft.

"'The experiment was made under unfavourable circumstances; the western extremity being only partially open, the ventilation is less perfect than it will be when the work is completed; the steam of the locomotive engine was also suffered to escape for twenty minutes, while the carriages were stationary, near the end of the tunnel; even during our stay near the unfinished end of the tunnel, where the engine remained stationary, although the cloud caused by the steam was visible near the roof, the air for many feet above our heads remained clear, and apparently unaffected by steam or effluvia of any kind, neither was there any damp or cold perceptible. We found the atmosphere of the tunnel dry, and of an agreeable temperature, and free from smell; the lamps of the carriages were lighted, and in our transit inwards and back again to the mouth of the tunnel the sensation experienced was precisely that of travelling in a coach by night between the walls of a narrow street; the noise did not prevent easy conversation, nor appear to be much greater in the tunnel than in the open air.

"'Judging from this experiment, and knowing the ease and certainty with which through ventilation may be effected, we are decidedly of opinion that the dangers incurred in passing through well-constructed tunnels are no greater than these incurred in ordinary travelling upon an open railway or upon a turnpike road, and that the apprehensions which have been expressed, that such tunnels are likely to prove detrimental to the health, or inconvenient to the feelings of those who may go through them, are perfectly futile and groundless.'